7. File System (ii)

05/25/2022 By Angold Wang

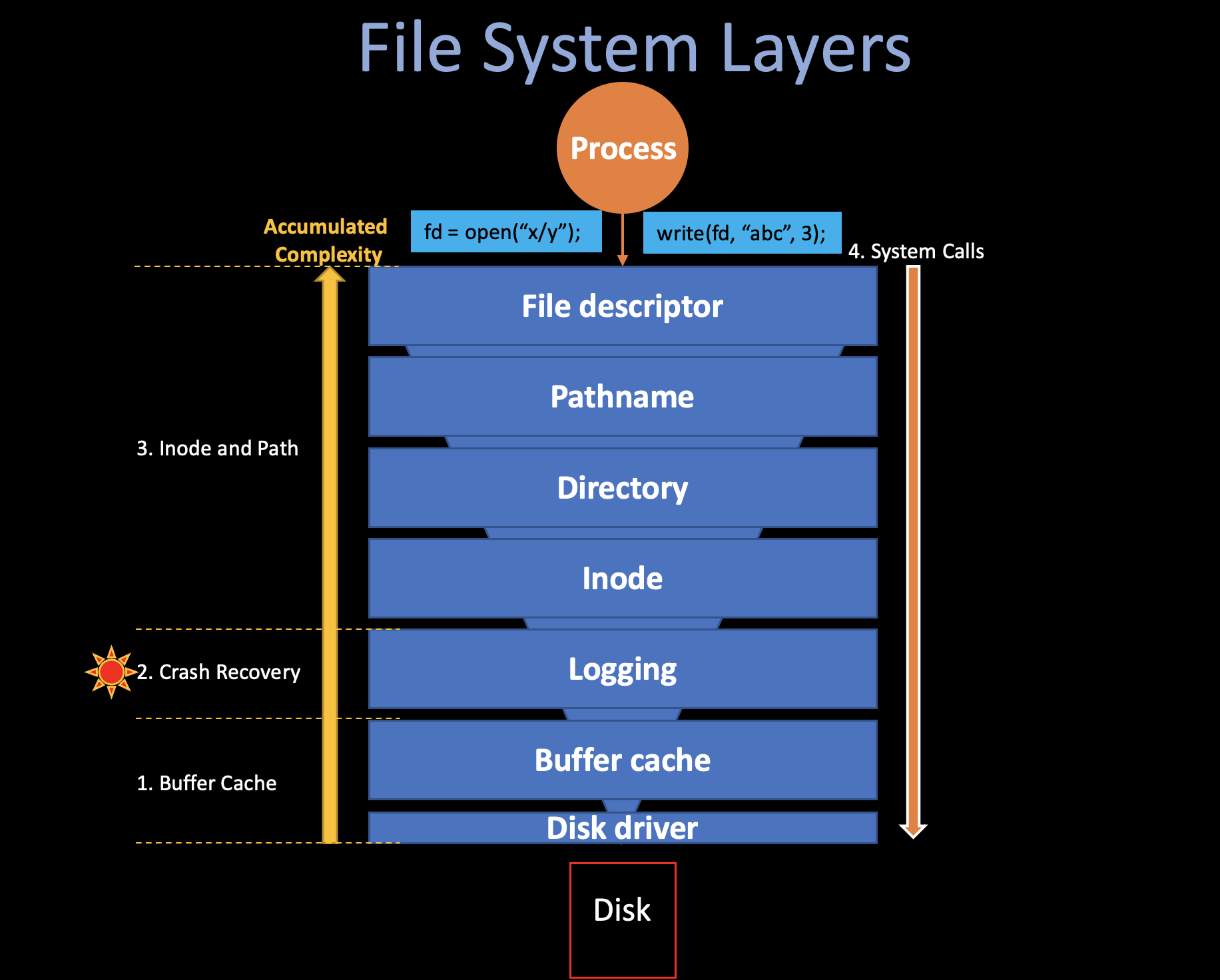

3. Inode and Path

Up until log, these lower layers are all interacting with

disk blocks (sectors) with a specific blockno. But

in the file systems that we are using in our daily life, seems that we

are manipulating data on specific files, and finding

them using path names.

The upper layers (layer 4, 5, 6, 7) is trying to ease the user by providing path, file, directory, etc, which we are familar with.

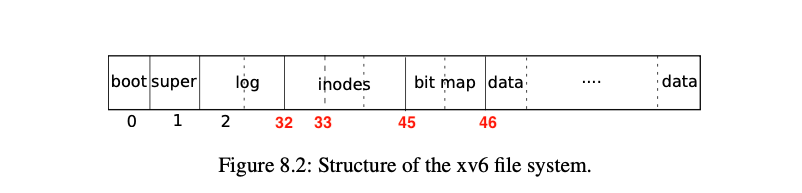

i. Block Allocator

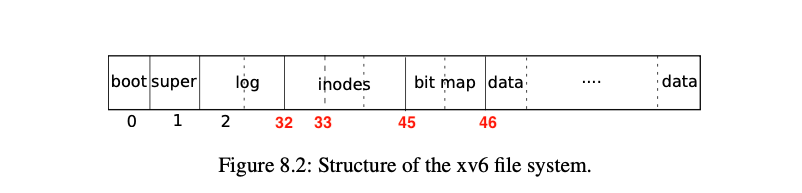

File and directory is stored in disk blocks, which must be allocated from a free pool. Xv6’s block allocator maintains a bitmap on disk, with one bit per block. A zero bit indicates that the corresponding block is free; a one bit indicates that it is in use.

The main API function that the block allocator provided is

balloc() which allocates a new disk block

and return its blockno. The loop inside

balloc is split into two pieces: * The outer loop reads

each block of bitmap bits (on disk). * The inner loop checks all

Bits-Per-Block(BPB) bits in a single bitmap block.

The loop looks for a block whose bitmap bit is zero, indicating that

it is free. If balloc finds such a block,

it updates the block and writes it to the disk (log_write)

then return the blockno of that block.

// kernel/fs.c:

for(b = 0; b < sb.size; b += BPB){

// for each bitmap block

bp = bread(dev, BBLOCK(b, sb));

for(bi = 0; bi < BPB && b + bi < sb.size; bi++){

m = 1 << (bi % 8);

if((bp->data[bi/8] & m) == 0){ // Is block free?

bp->data[bi/8] |= m; // Mark block in use.

log_write(bp); // write to the log buffer (bitmap -> disk)

brelse(bp);

bzero(dev, b + bi);

return b + bi;

}

}

}ii. Inode

You should view File System as many on-disk data structures. (tree, dirs, inodes, blocks) with two allocation pools: (blocks and inodes)

Up to now, we walk through one of the two allocations pools in Xv6 - the blocks and understand how the file system manipulate this on-disk data structures. The next part would be another allocation pool: inodes.

First let’s do not talk about the code or even design, let’s look at xv6 in action with some real system calls and illustrade on-disk data structure via how updated.

Here is the sequence of disk writes involved in each operation of

these two write system calls in echo (user/echo.c). We can

track these syscalls by adding a printf statement in

log_write, which will be called when a atomic series of

disk writes happends. (e.g,. a write system call).

$ echo "hi" > x

--- create the file

log write block: 33 // by ialloc: allocate inode in inode block 33

log write block: 33 // by iupdate: update inode (e.g., set nlink)

log write block: 70 // by writei: write to the data block of this directory entry (dirlink)

log write block: 32 // by iupdate: update the directory inode since we change the size of it.

log write block: 33 // by iupdate: itrunc new inode (even through nothing changed)

--- write "hi" to file x

log write block: 45 // by balloc: allocate a block in bitmap block 45

log write block: 628 // by bzero: zero the allocated block

log write block: 628 // by writei: write to it (hi)

log write block: 33 // by iupdate: update inode

--- write "\n" to file x

log write block: 628 // by writei: write to it (\n)

log write block: 33 // by iupdate: update inode

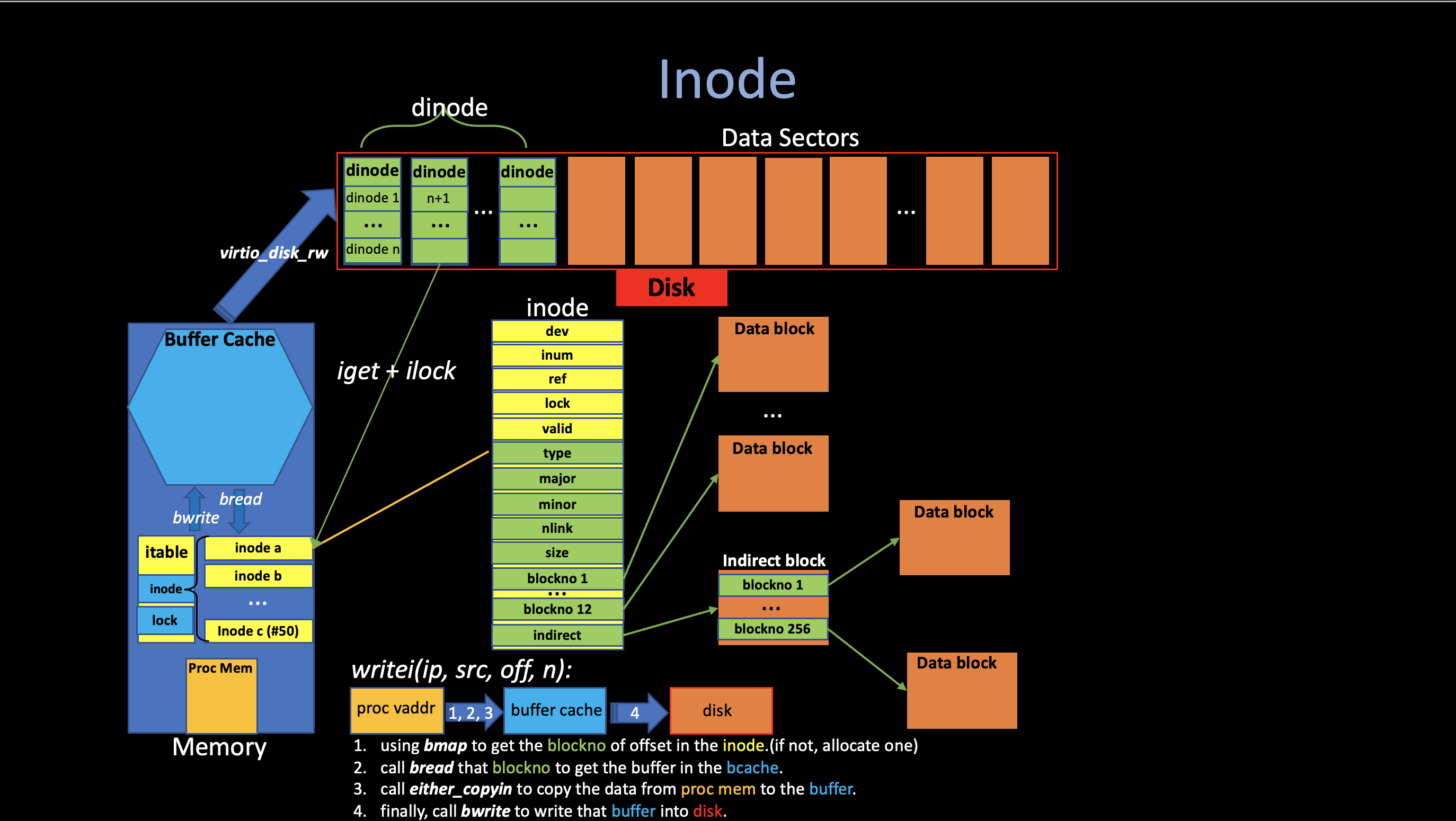

1. Inode Design

The term inode stands for two things in xv6: * On-disk datastructure containing a file’s size and list of data block numbers * In-memory copy of this disk inode in the inode table contains extra informantion needed within the kernel.

Disk Inode dinode

// kernel/fs.h

// On-disk inode structure

struct dinode {

short type; // File type

short major; // Major device number (T_DEVICE only)

short minor; // Minor device number (T_DEVICE only)

short nlink; // Number of links to inode in file system

uint size; // Size of file (bytes)

uint addrs[NDIRECT+1]; // Data block addresses (blockno)

};The on-disk inodes are packed into a contiguous area of disk called

the inode blocks. Just like block, every inode is in

the same size, so it is easy, given a number n, to find the nth node on

the disk. And this number n, called the inode number of i-number

(inum).

This on-disk inode structure, dinode,

contains a size and an array of block numbers. (the green part of the

following figure). The inode data is found in block listed in the

dinode’s’

addr array, and every elements of this

array is a blockno referring to a block in

the disk.

- The first

NDIRECTblocks of data are listed in the firstNDIRECTentries in the array, called direct blocks.- size of the direct blocks:

12(NDIRECT)*1024(BSIZE) =12KB.

- size of the direct blocks:

- The next

NINDIRECTblocks of data are listed in the last entry in theaddrsarray are address of the indirect blocks.- size of the indirect blocks:

1024 / 4(BSIZE / sizeof(uint) *1024(BSIZE) =256KB.

- size of the indirect blocks:

- So the Maximum size of a file in xv6 is

12KB + 256KB = 268KB.

In-memory Inode inode

// kernel/file.h

// in-memory copy of an inode

struct inode {

uint dev; // Device number

uint inum; // Inode number

int ref; // Reference count

struct sleeplock lock; // protects everything below here

int valid; // inode has been read from disk?

// copy of disk inode

short type;

short major;

short minor;

short nlink;

uint size;

uint addrs[NDIRECT+1];

};The inode is the in-memory copy of the

dinode on disk with some extra attributes

for File Systems to manipulate them: * The

inum record the inode number of that inode in order to

read/write them to/from disk. * ref field

counts the number of C pointers referring this in-memory

inode.

Inode Table itable

// kernel/fs.c

struct {

struct spinlock lock;

struct inode inode[NINODE];

} itable;An inode describes a single file or directory, the kernel

keeps a table in-use inodes in memory called itable to

provide a place for synchronization access. (also cache

frequently-used inodes) The kernel stores an inode in memory only if

there are C pointers referring to that inode.

(open).

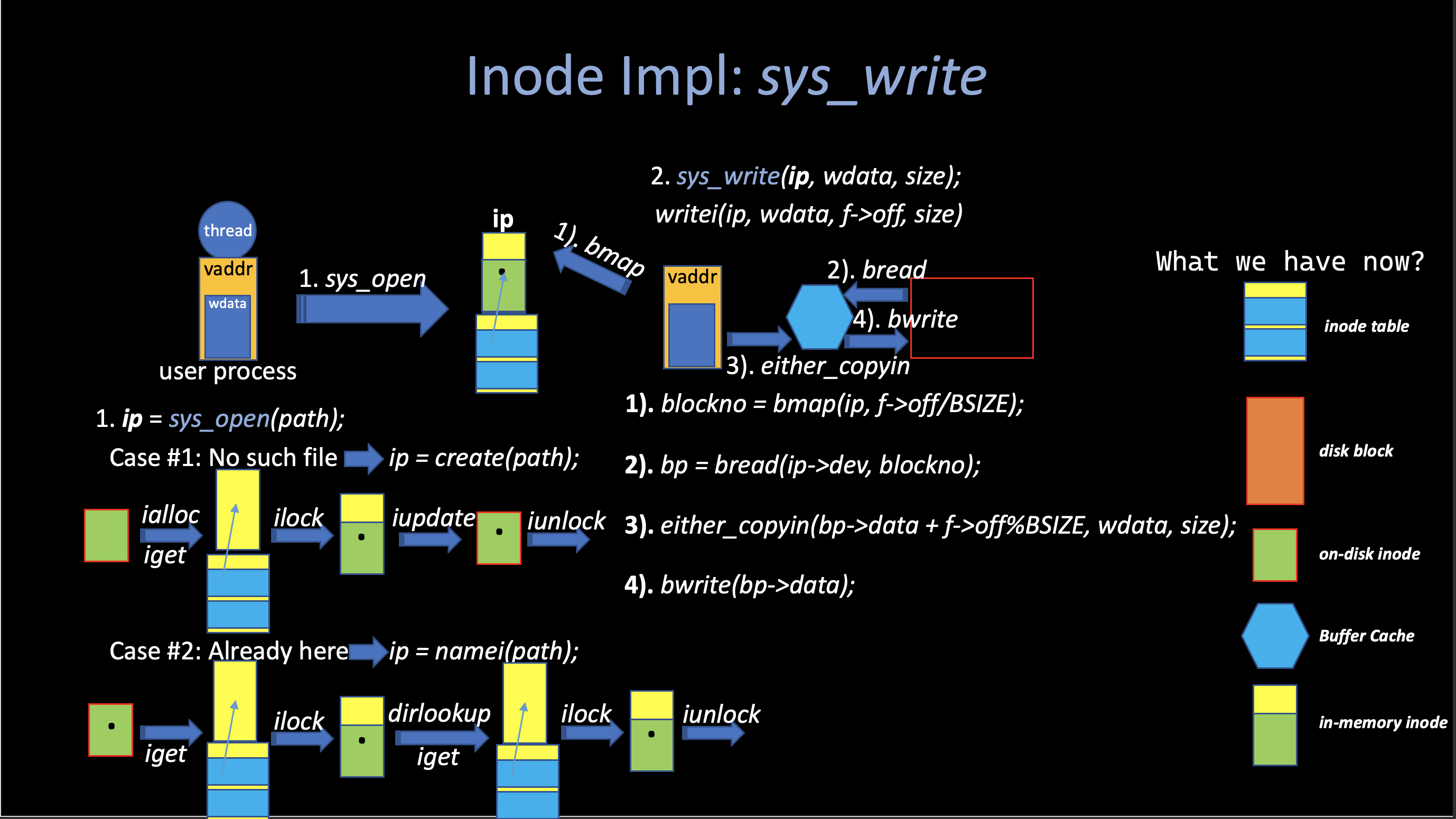

2. Inode Implementation

There are several api functions in the Inode layer, although xv6 uses very straightforward but non-efficient algorithms in the most part of its implementation, it is still quite hard to understand all of them with a simple description of each of them.

The following figure shows the all procedures related to inode when a user process make a write system call.

There are many functions related to the inode, all of them are in

kernel/fs.c. If you are trying to

understand the actual implementation, I highly recommend you to read the

source code, just like I said before, it is pretty straightforward.

There are three functions worth

mentioning:bmap,

ilock and

iput.

bmap(ip, f->off/BSIZE): returns the blockno of specific offset of inodeip.

The function bmap manage the complexity

of blocks representation in inode.addr[]

so that higher-level routines, such as

readi and

writei, do not need to deal with this

complexity. bmap(ip, bn) returns the disk

block number of the bn’th data block for

the inode ip. If

ip does not have such a block yet,

bmap allocates one.

Bigfile: Note that in the current xv6 implementation, the files are limited to 268KB, this limit comes from the fact that an xv6 inode contains 12 “direct” block number and one “singly-indirect” block number, which refers to a block that holds up to 256 more block numbers. If we want to increase the maximum size of an xv6 file, like adding a “double-indirect” block in each inode, containing 256 addresses of singly-indirect blocks, each of which can contain up to 256 addresses of data blocks. The result will be consist of up to (

256*256 + 11 + 256) 65803 blocks, We can do this by changing thisbmapfunction to make it support double indirection, you can see a implementation here: bigfile.

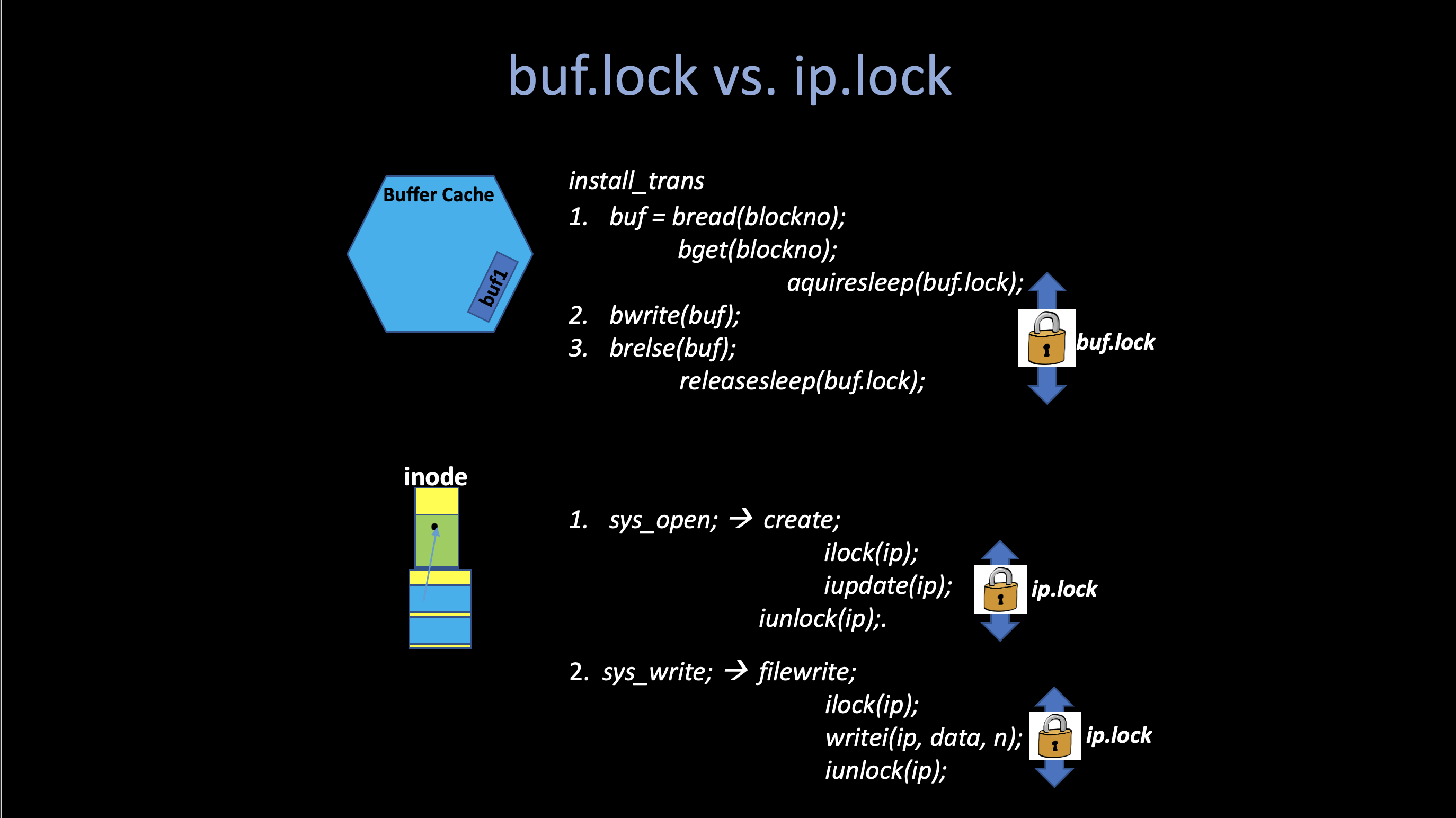

ilock(ip): lock the given inode and reads the inode from disk.

Typically, the lock is used to prevent some harzards come from synchronization access of shared data, which make sure that at any time, only one process that holding the lock can change that the protected data.

But too much locking especially locking for too long may also cause

many problems such as deadlock. In the 1.

buffer cache part, I said the way to prevent multiple kernel

thread use that copy of disk block is everytime when

bwrite wants to write something to the

disk, it should always call bread, and

bread will call

bget to return a locked buffer in the

buffer cache, after writes finished, it will call

brelse to release that buffer lock.

And the situation is a little bit different here: If you want to

write something to a file (i.e., calling

file_write), you always need to first open

that file (sys_open) and you cannot hold the lock when open

it because you don’t know when you gonna write something to it. So when

you call iget in order to get a entry in

the global inode table (itable), you

cannot hold the lock of that inode because you don’t know when to

release it. If you keep holding it, it may causes

deadlock and races when you do some

operations like directory lookup, etc.

The xv6 prevent this from happening by seperating the

ilock and

iget so that the system call can get

a long-term reference to an inode (as for an open file), and

only lock it for a short period when needed (e.g., in

read()). And iget

only increments the ip->ref so that the inode stays in

the table and pointers to it remain valid.

Worth mentioning that another thing

ilock will do is read the inode data from

the disk dinode, that is because we do not

keep holding that ip.lock before and this

inode may have changed by another process and we have to get those

changes from disk.

iput(ip): drop a reference to an in-memory inode and free it (also its content) in disk if ref goes 0.

iput releases a C pointer to an inode

and that the inode has no links to it (i.e., no directory has

link to it), if this is the last reference, then the inode and

its data blocks must be freed. iput calls

itrunc to truncatre the file to zero

bytes, freeing the data blocks; sets the inode type to 0 (unallocated);

and writes the inode to disk.

iii. Directory

A directory is implemented internally much like a file. Its inode has

type T_DIR and its data in the data block is a sequence of

directory entries. Each entry is a struct dirent,

which contains a name (name) its inode number

(inum). The name is at most

DIRSIZ(14) characters; if shorter, it is terminated by a

NUL(0) byte. Directory entries with inode number zero are

free.

// kernel/fs.h

struct dirent {

ushort inum;

char name[DIRSIZ]; // 14

};There are two main API functions in this layer:

dirlookup and

dirlink.

dirlookup: look for a directory entry/file inode in a directory.

// kernel/fs.c

for(off = 0; off < dp->size; off += sizeof(de)){

// the data inside directory inode (addr) is the address of dirent

if(readi(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de))

// read data from disk inode to de

panic("dirlookup read");

if(de.inum == 0)

continue;

if(namecmp(name, de.name) == 0){

// entry matches path element

if(poff)

*poff = off;

inum = de.inum; // directory entry

return iget(dp->dev, inum);

// allocate a inode in the inode table

// and then return the address of that inode in the table

}

}The main loop is also very straightforward: it searches a directory

for an entry with the given name. It it finds one, it updates

*poff to the byte offset of the entry within the

directory(in case the caller wishes to edit it) and returns an unlocked

inode in the itable obtained via

iget.

Here dirlookup is one reason that

iget returns unlocked inodes that I

mentioned before: Since everytime when a system call wants to

call dirlookup(ip, name), it should always hold the lock

(ip->lock) before entering it to avoid other process

changing its data while dirlookup is reading in it. Imagine

the look up is for . ($ls .), an alias for the

current directory, attemping to lock the inode before returning would

try to re-lock ip (by iget) and

deadlock.

dirlink: write a directory entry (name, inum) into the directory dp.

The main loop reads directory entries looking for a unallocated entry

(de.inum == 0). The usually call stack will be:

dp = namex(path, name) ->

ip = ialloc(dp->dev) ->

dirlink(dp, name, ip->inum)

iv. Path Name

Path name lookup (namex) involves a

sucession of calls to dirlookup

(iteration), namei evaluetes

path and returns the corresponding

inode.

Here again we see why the separation between

iget and

ilock is important:

The procedure namex may take a long

time to complete: it should involve several disk operations to read

inodes and directory blocks for the directories traversed in the

pathname (if they are not in the buffer cache). So we must allow

parallel pathname lookup, which means lookups in different directoryies

can proceed in parallel.

Let’s look at namex()

(kernel/fs.c):

// kernel/fs.c

if(*path == '/')

ip = iget(ROOTDEV, ROOTINO);

else

ip = idup(myproc()->cwd);

while((path = skipelem(path, name)) != 0){

ilock(ip); // read the inode from disk

...

if((next = dirlookup(ip, name, 0)) == 0){

iunlockput(ip);

return 0;

}

iunlockput(ip);

ip = next; // next -> iteration

...

}

return ip;iget(ip): get the directory inode at in creasing itsrefin the inode table.ilock(ip): locks current directory.dirlookup(ip, name): find next directory inode.iunlockput(ip): unlock current directory.

Another process may unlink the next inode, but inode won’t be

deleted, because inode’s ref > 0 (by

iget()). and finally the

iunlockput() will both call iunlock() and

iput() to unlock it and decreasing its

ref.

Also same as the deadlock. For example,

next points to te same inode as

ip when looking up “.”.

Locking next before releasing the lock on ip

would result in a deadlock. To avoid this deadlock,

namex unlocks the directory before

obtaining a lock on next, just as we’ve seen before.

Key Idea: getting a reference separately from locking

The skipelem(path, name) is used for

managing the complexity of pathname.

For example: to resolve

path = skipelem(path, name), where

path = os/docs/lectures/6FS.md. this

skipelem will return the path

equal to docs/lectures/6FS.md and setting name

equal to os.

v. File Descriptor

A cool aspect of Unix interface is that most resources in Unix are represented as files. Including devices such as the console, pipes, and of course, real files. The File Descriptor layer is the layer that achieves this uniformity.

In xv6, each process has its own table of open files

(*ofile[NOFILE]; (16)), so-called file

descriptors, which is just a wrapper around either an

inode or a pipe, plus an I/O offset, and previlegies like

readable and writeable.

// kernel/proc.h

// Per-process state

struct proc {

...

struct file *ofile[NOFILE]; // Open files

...

}

// kernel/file.h

struct file {

// which is wrapper around either an inode or a pipe,

// plus an I/O offset

enum { FD_NONE, FD_PIPE, FD_INODE, FD_DEVICE } type;

int ref; // reference count

char readable;

char writable;

struct pipe *pipe; // FD_PIPE

struct inode *ip; // FD_INODE and FD_DEVICE

uint off; // FD_INODE

short major; // FD_DEVICE

};This brings two “independency”: * If multiple processes open

the same file independently, the different instance will have differnt

I/O offsets. * A single open file can appear multiple

times in one process’s file table, and dup can use this to

create alias.

Just as xv6 implemented in lower layers.

(bcache, logheader and

itable), there also a place to store all opened

files, and this global file table called

ftable, make sure that only one copy of

the disk file (inode) resides in the file system (for synchronization

access).

struct {

struct spinlock lock;

struct file file[NFILE];

} ftable;The file descriptor layer provides the top-level API

functions to allocate a file (filealloc),

create a duplicate reference (filedup),

release a reference (fileclose), and read

and write data (fileread and

filewrite). All of them will call the APIs

that lower-level provides to do the actual work.

4. System Calls

All files related to File System’s syscall is in

kernel/sysfile.c. And they just the

very-top level layer which uses the lower-layer services.

With the functions that the lower layers provide the implementation of most system calls is trivial. Like what I mentioned in the intro part of 6. File Systems (i), this bottom-up view will help you to understand the design purpose of each layers.

Now lets take a top-down view of the whole file

system by walking through the actual implementation of System calls,

just to make this all concrete. I am using the same example here - the

echo "hi" example we’ve seen in the

inode part of this article. But this time, we track the

bwrite() instead of the log_write(), which

shows all the writes to disk in the buffer cache. And we can see the

trace of what actual disk writes are.

This trace is way longer than the trace that we’ve looked at last time:

$ echo "hi" > x

// create the file

bwrite: 3 // write_log: new allocated inode block 33 -> log 3 in disk (by ialloc + iupdate)

bwrite: 4 // write_log: directory inode 70 -> log 4 in disk (directory data) (by dirlink + writei)

bwrite: 5 // write_log: directory inode 32 -> log 5 in disk (directory inode) (by dirlink + iupdate)

bwrite: 2 // write_head: actual commit to the log header

bwrite: 33 // bwrite (iupdate): allocate inode and update inode for x (log absorption)

bwrite: 70 // bwrite (writei): write to the data block of this directory entry

bwrite: 32 // bwrite (iupdate): update the directory inode since we change the size of it

bwrite: 2 // write_head: clear the log (make log "empty")

// write "hi" to file x

bwrite: 3 // write_log: set the bit of new allocated block in 45 bitmap -> log 3 in disk (by bmap + balloc)

bwrite: 4 // write_log: zero that block and then write hi to it -> log 4 in disk (by bzero + writei)

bwrite: 2 // write_head: actual commit to the header

bwrite: 45 // bwrite (balloc): allocate a block in bitmap block 45

bwrite: 628 // bwrite (writei): zero the allocated block and write "hi"

bwrite: 33 // bwrite (iupdate): update the inode of file x

bwrite: 2 // write_head: clear the log (make log "empty")

// write "\n" to file x

bwrite: 3 // write_log: zero that block and then write hi to it -> log 3 in disk (by bzero + writei)

bwrite: 4 // write_log: update the file's inode 33 -> log 4 in disk (by iupdate)

bwrite: 2 // write_head: actual commit to the header

bwrite: 628 // bwrite (writei): write "\n"

bwrite: 33 // bwrite (iupdate): update the inode of file x

bwrite: 2 // write_head: clear the log (make log "empty")

If you walkthough all block writes above, and you can both tell “After write that block, what we can get?” and more important, “Why we should write that block?”, I believe that can makes you to have a comprehensive understanding of xv6 File System with both view to it, and hope it will benefit your journey in database world, modern operating system world, or even any system design world…

Although most part of xv6 uses very straightforward and inefficient implementation for simplicity, it still shares the same purpose and some design choice at each layer with the mordern operating systems, which is significantly more complex than xv6’s.

Thanks for your reading! If you have any questions or promlems in this article, just feel free to mail me at wangold4w@gmail.com or comment below. I’m happy to see that :).

See you next time.

this page was last edited on 29 May 2022, at 11:45 (UTC), by Angold Wang.