6. File System (i)

05/20/2022 By Angold Wang

File Systems is one of the most special place in Operating System. it organize the stored data in hard disk, and maintain the persistence so that after a reboot, the data is still available.

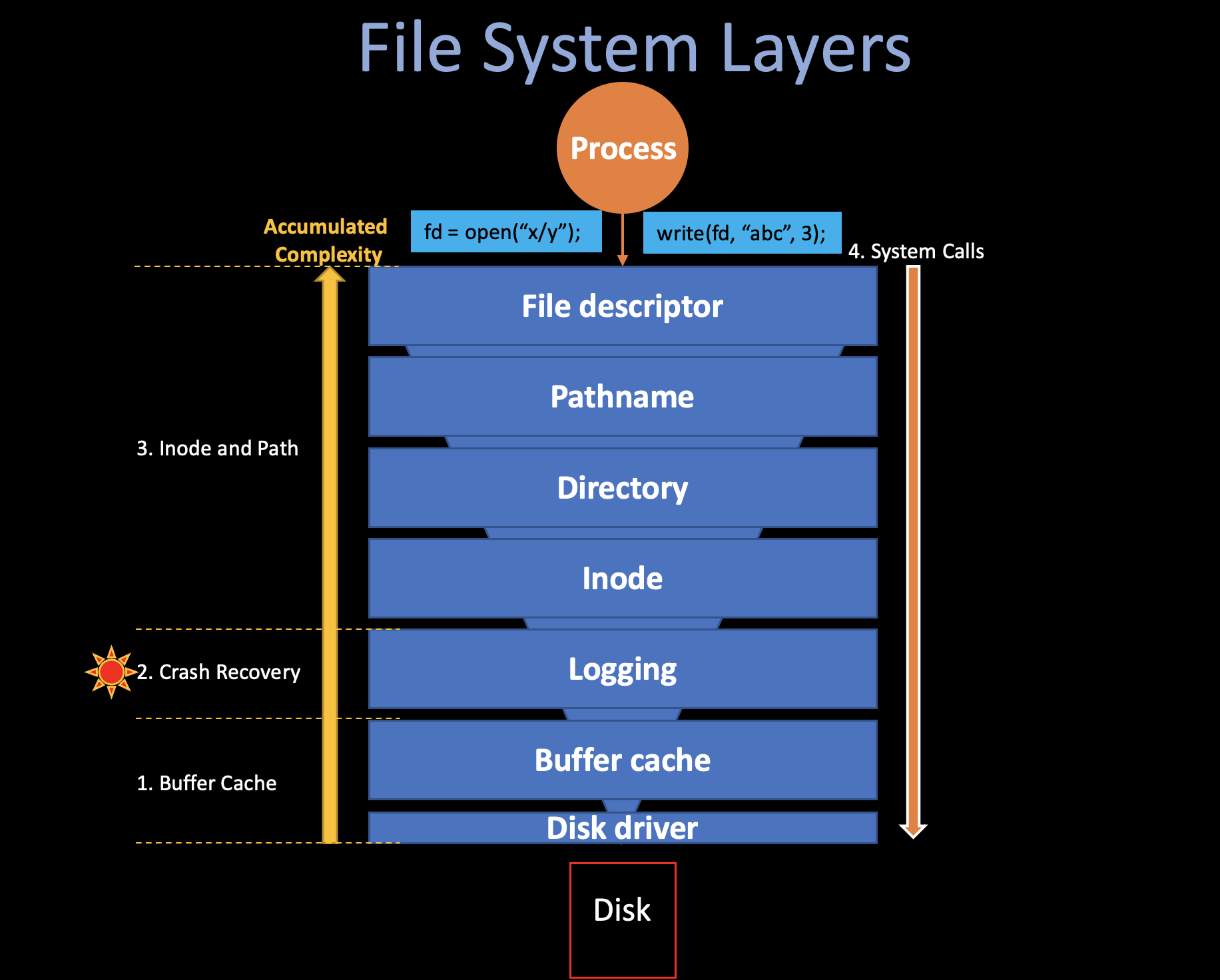

The xv6 file system implementation is organized in seven layers, shown in the following figure.

Layer 1&2: Buffer Cache & Disk Driver

Accessing a disk is orders of magnitude slower than accessing memory, so the file system must maintain an in-memory cache of popular blocks, the buffer cache layer caches disk blocks and synchronizes access to them, making sure that only one kernel process at a time can modify the data stored in any particular block.

Layer 3: Logging

The Logging layer helps the file system to support Crash Recovery, that is, allow higher layers to wrap updates to several blocks in a transactions, and ensures that the blocks are updated atomically in the face of crashes (i.e., all of them are updated or none).

If a crash (e.g., power failure) occurs, the file system must still work correctly after restart. The risk is that a crash might interrupt a sequence of updates and leave inconsistent on-disk data structures (e.g., a block that is both used in a file and marked free).

Layer 4&5&6&7: Inode & Path

The file system needs on-disk data structures to represent the tree of named directories and files, to record the identities of the blocks that hold each file’s content, and to record which areas of the disk are free.

In xv6, each file will be represented as an Inode,

and the directory is a special kind of inde whose content is a sequence

of directory entries. And the pathname layer provides hierachical path

names like /usr/angold/xv6/fs.c, and resolves them with

recursive look up. Finally, at the very top layer, the file

descriptor abstracts many Unix resources (e.g., pipes, devices,

files.) using the lower-layers interface we mentioned above,

simplifying the lives of application programmers.

Accumulated Complexity

There are two ways to understand the file system: Bottom-up and Top-down, we call the former “OS Designer’s Perspective” and the latter “Application’s Programmer’s perspective”.

In the Top-down View, each API at the top layer

(write,

open, close)

will be treated as serial instructions, that is: the call

stack (fn1() -> fn2() ->…

etc,.), which is relatively easy to figure out how does the fs

works (by going through each routines), but it is very hard to

understand what is the design purpose of each layer due

to the accumlation of complexity at the high level. (it may also costs

much time to walk through each routines, especially in some big

systems)

In the Bottom-up View, when you start at the lowest level, the complexity is usually relatively small (code size, less routines…), and one more important thing is that the higher level usually depends on the lower level underneath, which means after you understand these low-level stuff, the upper layer code seems highly structured. (lower layers ease the design of higher ones)

In the following two articles (fs(i) & fs(2)), we will study the xv6 File System in both Top-down and Bottom-up view in order to have a fully understanding of File System, and answer questions like: “how does file system works” and “why it looks like that (the design choice)”. I believe the File System is a brilliant example to learn the “Accumulated Complexity” in System Engineering.

1. Buffer Cache

i. Disk Driver

Disk hardware traditionally presents the data on disk as a numbered sequence of 512-byte blocks (sectors). > The block size that an operating system uses for its file system maybe different than the sector size that a disk uses, but typically the block size is a multiple of the sector size.

Each block on Disk has its own unique blockno,

indicating the offset of specific data in disk. (sector 0 is the first

512 bytes, sector 1 is the next, and so on…)

The file system must have a plan for where it stores specific data

(i.e., indes, data) on disk, to do so, when xv6 boots, the

mkfs (kernel/mkfs.c) will build the entile

file system, you should see the following output from mkfs

in the make output:

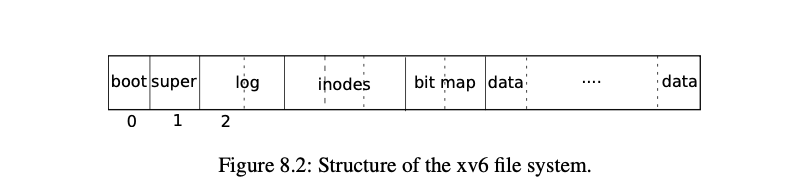

nmeta 70 (boot, super, log blocks 30 inode blocks 13, bitmap blocks 25) blocks 199930 total 200000As you can see, xv6 divides the disk into several sections, as Figure 8.2 shows. The fils system does not use block 0 (it holds the boot sector). Block 1 is called super block; it contains metadata about the file system: * The number of data blocks * The number of inodes * The number of blocks in the log * …

The code of disk driver of xv6 is in

kernel/virtio_disk.c, typically, anytime the xv6 wants to

read/write the data from disk, it will call

virtio_disk_rw(struct buf *b, int write), the data

structure buf contains a specific buffer inside the buffer

cache, where contains the target blockno.

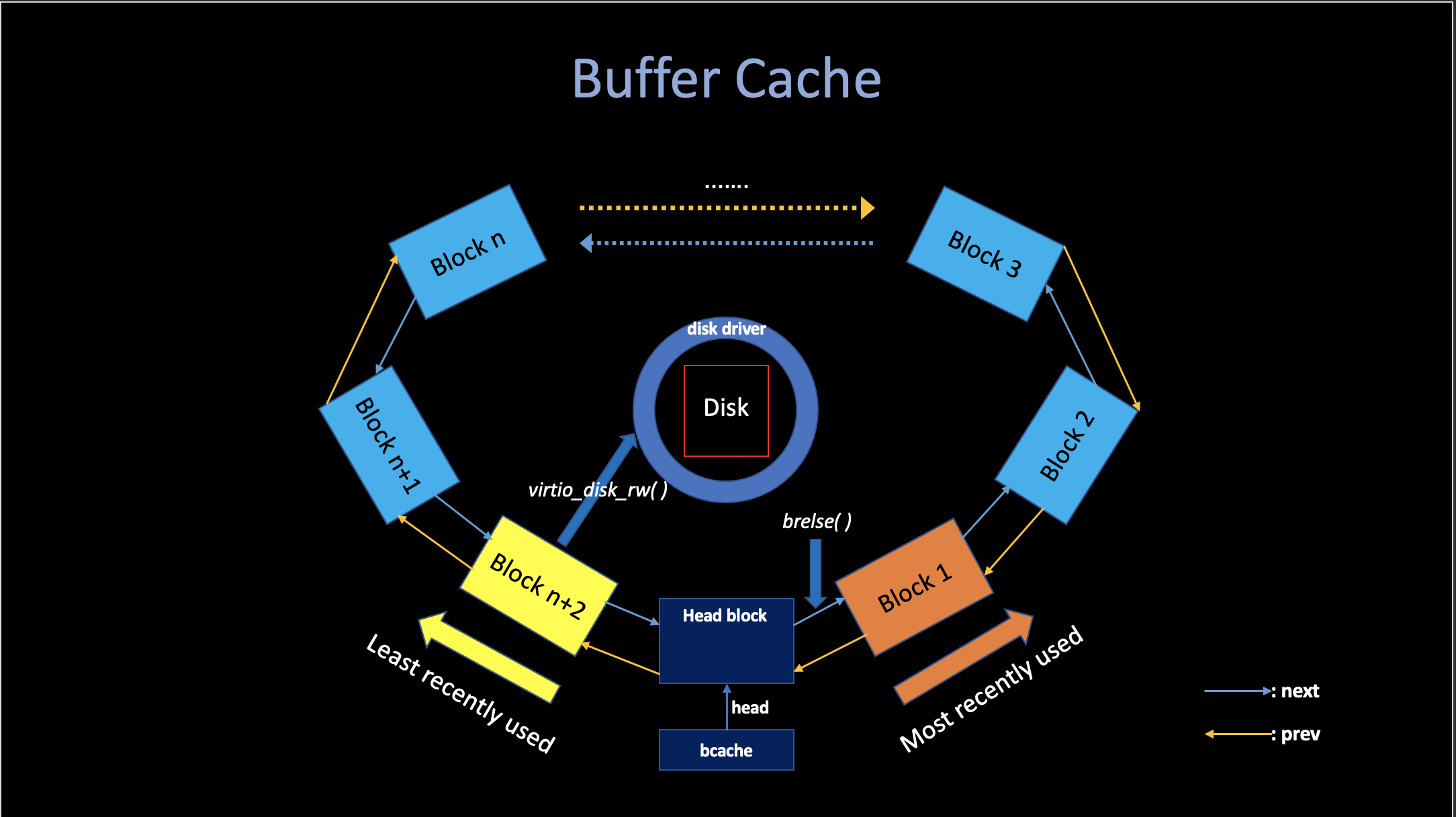

ii. Buffer Cache

The Buffer Cache has two jobs: 1. Cache popular blocks so that they don’t need to be re-read from the slow disk. 2. Synchronize access to disk block to ensure that only one copy of a block is in memory and that only one kernel thread at a time uses that copy.

The buffer cache has a fixed number of buffers to hold disk blocks, which means that if the file system asks for a block that is not already in the cache, the buffer cache must recycle a buffer currently holding some other block. The buffer cache recycles the least recently used (LRU) buffer for the new block.

Buffer

// kernel/buf.h

struct buf {

int valid; // has data been read from disk?

int disk; // does disk "own" buf?

uint dev;

uint blockno; // disk hardware can use blockno to find data

struct sleeplock lock;

uint refcnt;

struct buf *prev; // LRU cache list

struct buf *next;

uchar data[BSIZE]; // the stored 512 byte data

};A buffer has two state fields associated with it:

buf.refcntindicates that how many process currently own that buffer. ( means doing some read/write on it )buf.validindicates that the buffer contains a copy of the block., thevalidis set to 1 when someone read specific disk data into block by callingbread(), and will be set to 0 if itsrefcntequal to 0 and being recycled.

Lock (Prevent Multiple Access)

As we said before, one of the main purpose of buffer cache is to prevent multiple kernel thread use that copy of disk block, and this mechanism is supported by the Lock.

bget (kernel/bio.c)

returns a free buffer in the buffer cache, it scans the

buffer list for a buffer with the given divice and sector numbers. If

there is such buffer, bget acquires the

sleep-lock for the buffer to

prevent multiple access (different kernel thread) and then

returns the locked buffer. If there is no cached buffer for the given

sector, bget must make one by reusing a buffer that held a different

sector. (LRU).

bread (kernel/bio.c) calls

bget to get a locked buffer from buffer

cache for the given sector, and then call virtio_disk_rw to

read the data from disk.

Once bread has read the disk and

returned the locked buffer to its caller, the caller has exclusive use

of the buffer and can read or write the data bytes. If the

caller does modify the buffer, it must call bwrite to write

the changed data to disk before releasing the buffer.

Notice that there is at most one cached buffer per disk

sector, to ensure that readers see writes, and because the file

system uses locks on buffers for synchronization.

bget ensures this invariant by holding the

bcache.lock continuously during the whole procedure of

bget.

LRU Buffer Cache

The Buffer Cache is a doubly-linked list of buffers (more precisely, a circular linked list).

// kernel/bio.c

struct {

struct spinlock lock;

struct buf buf[NBUF]; // 13

// Double Linked list of all buffers, through prev/next.

// Sorted by how recently the buffer was used.

// head.next is most recent, head.prev is least.

struct buf head;

} bcache;

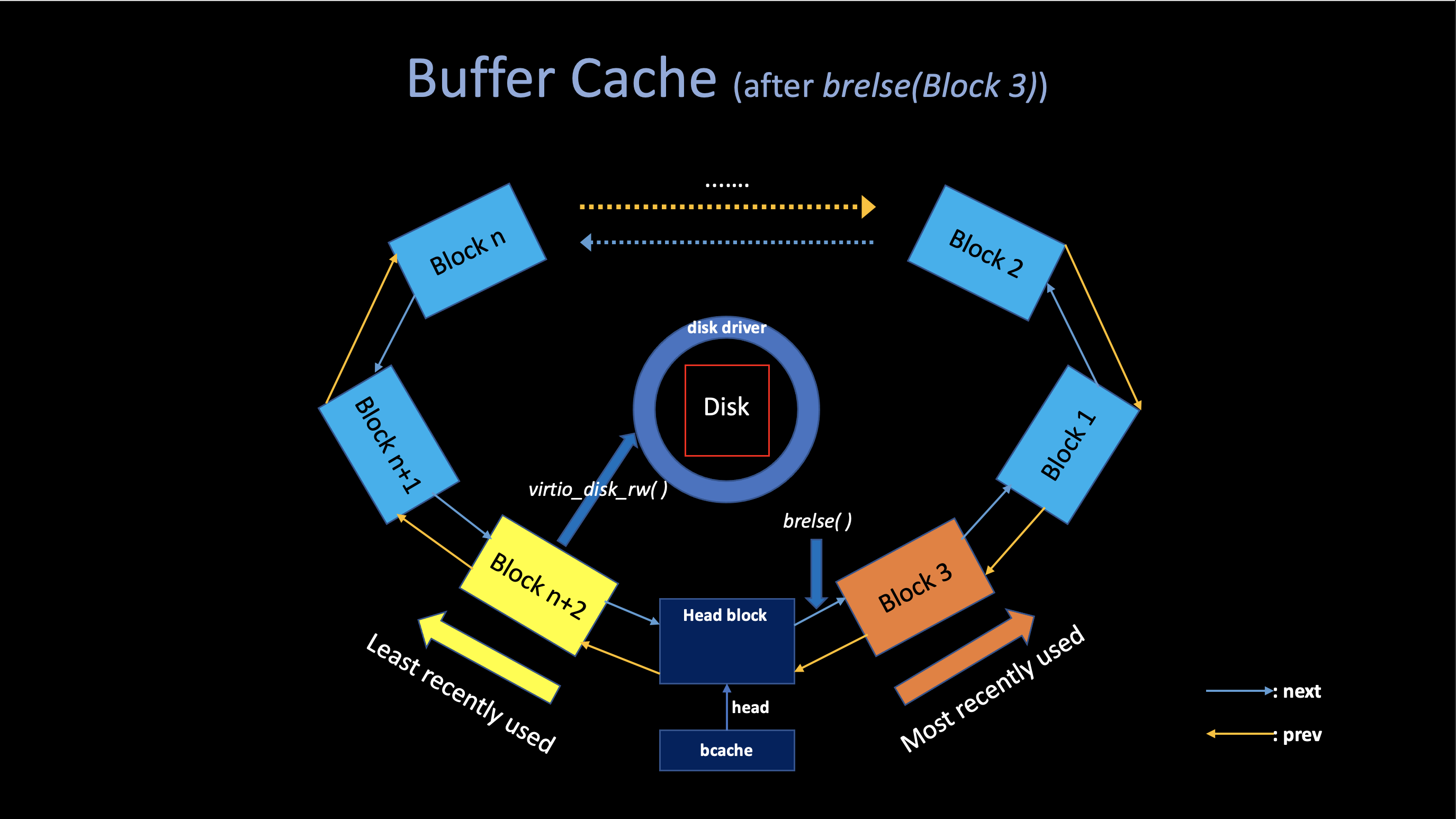

When the caller is done with a buffer, it must call

brelse(kernel/bio.c) to

release it, which will release the sleep-lock first in

order to allow other kernel thread using that buffer, The

brelse decreasing the refcnt

of that buffer, if it reaches zero, brelse

will move the buffer to the front of the linked

list.

Moving the buffer causes the list to be ordered by how recently the buffers were used:

The first buffer in the list is the most recently used and the last is the least recently used.

The two loops in bget take advantage of

this: * In the first loop, we want to check whether there is a

valid cached block. If we check the most recently used buffers

first (starting at bcache.head and following

next pointers) will reduce the scan time, where

there is a good locality of reference.

- If the first failed, In the second loop, we want to pick a

reusable block (

refcnt==0). If we check the least recently used buffers first (starting atbcache.headand followingprevpointers) will also reduce the scan time.

// See whether it is cached.

for(b = bcache.head.next; b != &bcache.head; b = b->next){

if(b->dev == dev && b->blockno == blockno){

b->refcnt++;

release(&bcache.lock);

acquiresleep(&b->lock);

return b;

}

}

// Not cached.

for(b = bcache.head.prev; b != &bcache.head; b = b->prev){

if(b->refcnt == 0) {

b->dev = dev;

b->blockno = blockno;

b->valid = 0;

b->refcnt = 1;

release(&bcache.lock);

acquiresleep(&b->lock);

return b;

}

}2. Crash Recovery

i. Problem: Inconsistent State on Disk

Imagine you are running $make interacting with the file

system, and somewhere doing that thing, a power failure happends(run out

of battery). After that, you plugin and reboot your machine, when you

run $ls, you hope your file system is in the good state.

A tricky case is that many file system operations have

multi-step operations, if we crash just in the wrong place in these

multi-step operations, the file system actually may end up being on this

inconsistent for that short period of time, and if the power failure

just happend there, something bad could happends.

ii. Solution: Logging

Xv6 solves the problem of crashes during file-system operations with a simple form of logging, which is originally coming out of the database world, and a lot of file systems using logging these days, one of the reason it is popular because it ia a very principled solution.

An xv6 system call does not directly write the on-disk file system data structures. Instead, it places a description of all the disk writes it wishes to make in a log on disk, once the system call has logged all of its writes, it writes a special commit record to the disk indicating that the log contains a complete operation. At that point the system the system call copies the writes to the on-disk file system data structures and finally erase the log on disk.

iii. Log Design

// kernel/log.c

struct logheader {

int n;

int block[LOGSIZE];

};

struct log {

struct spinlock lock;

int start;

int size;

int outstanding; // how many FS sys calls are executing.

int committing; // in commit(), please wait.

int dev;

struct logheader lh;

};The two main data structures of log is

logheader and

log, all of them are in

kernel/log.c. * log.start indicate the

start blockno inside disk, which will be used when

writing log to the disk. * log.outstanding counts

the number of system calls that have reserved log space. *

Incrementing log.outstanding both reserves space and

prevents a commit from occuring during this system call. * Decrementing

log.outstanding when a file system call finish its

write/read operations and ready to be commit. *

log.lh.n indicate the current log size of file

system. If it is greater than zero, we know that there are some

blocks in the log that need to be installed to the disk. *

log.lh.block[i] stores the blockno of

the start+i log on disk, which will be discussed

later.

The log resides at a known fixed location, specified in the

superblock. It consists of a header block followed by a sequence

of updated block copies (“logged blocks”). The header block

contains an array of sector numbers (log.lh.block), one for

each of the logged blocks, and the count of log blocks

(log.lh.n). The count in the header block on disk is either

zero, indicating that there is no transaction in the log, or non-zero,

indicating that the log contains a complete committed transaction with

the indicated number of logged blocks.

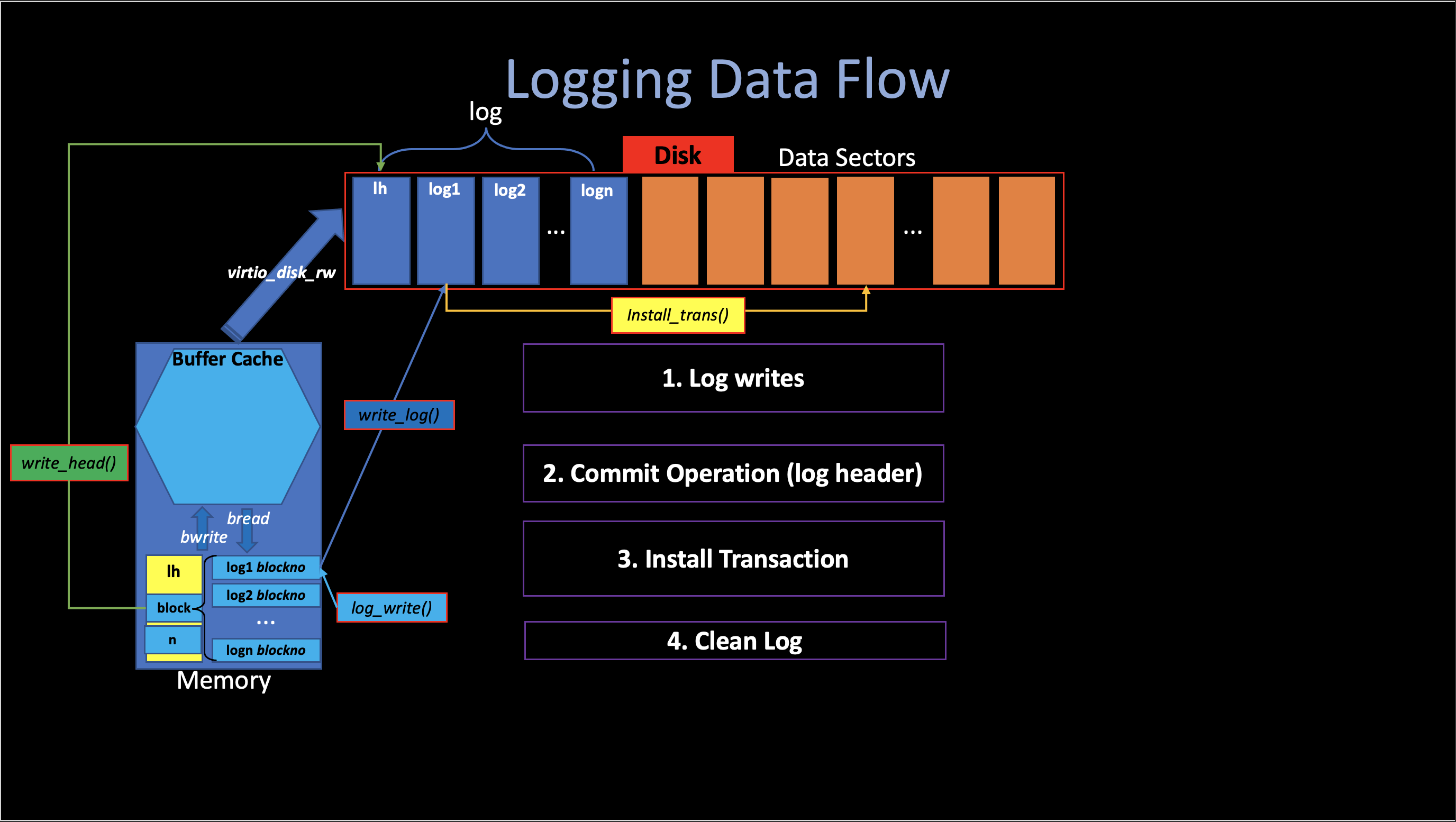

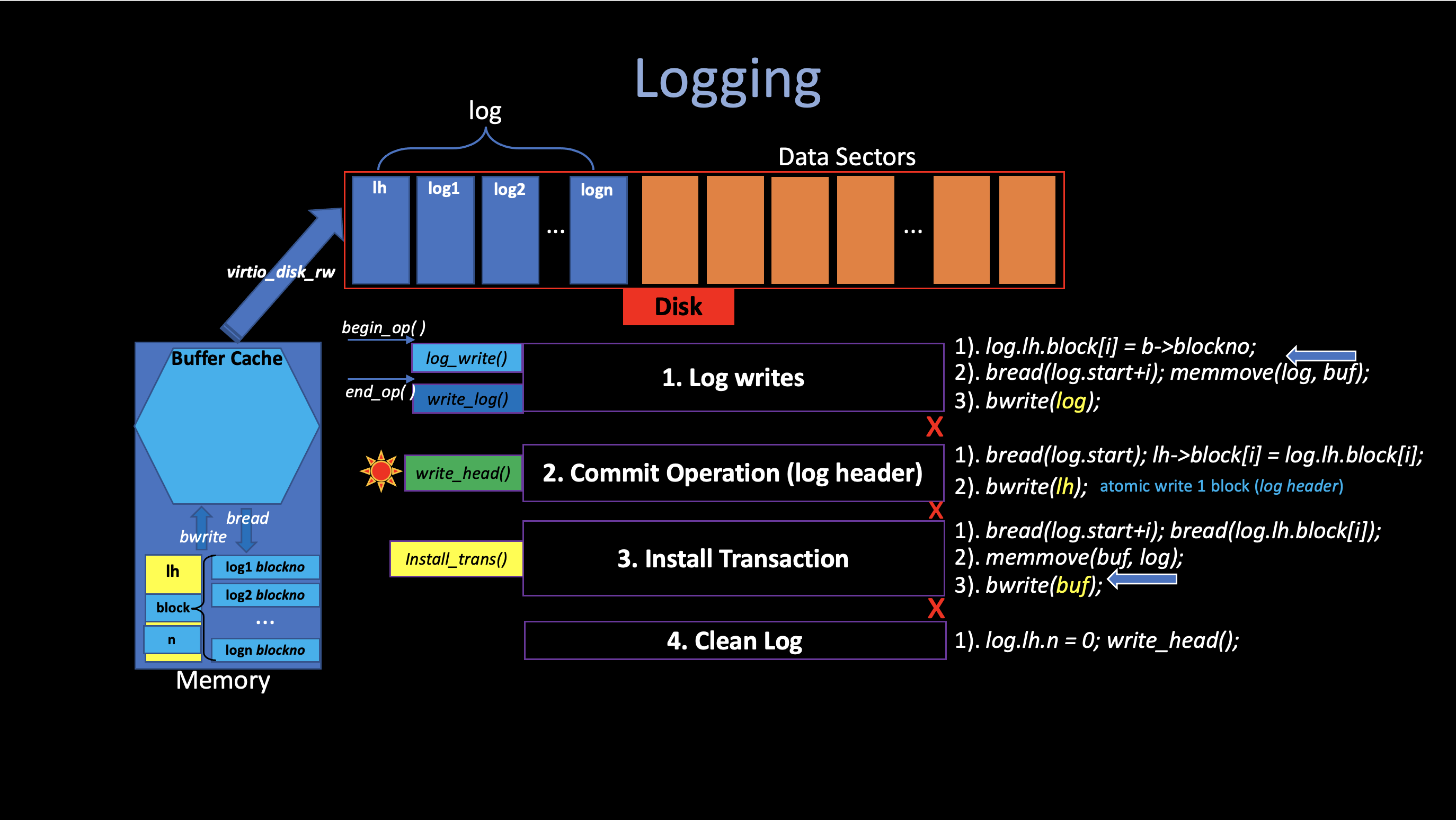

Here is a High-level picture of logging in xv6.

iv. Log Implementation

There are four phases in logging. Almost all related code are in

kernel/log.c:

Each system call’s code indicates the start and end of the

sequence of writes that must be atomic with respect to crashes.

The begin_op() and

end_op() will guarentee that all writes to

the disk blocks between this two functions calls will be atomic.

A typical use of the log in a system call looks like this:

begin_op();

...

bp = bread(...);

bp->data[...] = ...;

log_write(bp);

...

end_op();The begin_op() waits until the logging

system is not currently commiting (log.commiting) or there

is enough space in the log (LOGSIZE). It record the

current logging by increasing the log.outstanding

value.

1. Log writes

There are three phases in log writes:

1). log_write()

Every time the syscall calls bwrite to

write some data into buffer cache, after that, it will call

log_write in order to record that change.

The log_write will not write anything to

disk. It just record the blockno that has been

written to disk in log.block[i], which will reserve a slot

in the log in disk., and pins the buffer in the buffer cache to

prevent the bcache from evicting it.

Log Absorption: The

log_writenotices when a block is written multiple times during a single transaction, and allocates that block the same slot in the log. By absorbing several disk writes into one, the file system can save log space and achieve better performance because only one copy of disk must be written to disk.

2). end_op()

Like I mentioned before, after a system call finishes all writes to

buffer cache by calling bwrite, finally,

it will call end_op to write (commit) it

to disk.

end_op() first decrements the count of

outstanding system calls (log.outstanding). If the count is

now zero, which means all current system calls finish their writes to

disk, it commits the current transaction by calling

commit().

Group Commit:, To allow concurrent execution of file-system operations by different processes, the logging system can accumulate the writes of multiple system calls into one transaction. Thus a single commit may involve the writes of multiple complete system calls. Group commit reduces the number of disk operations because it amortizes the fixed cost of a commit over multiple operations.

3). write_log()

If the current log number is greater than zero

(log.lh.n > 0), The first thing

commit() will do is copy the

transaction buffers into their own log block on disk by calling

write_log().

The write_log() copies each block modified in

the transaction from the buffer cache to its slot in the log on

disk.

2. Commit Operation

The file system finish its commit by calling

write_head() in order to writes

the header block (log.lh) from the buffer cache to its slot

in the log on disk. At the point the file system do commit, all

the writes are in the log.

This step is pretty simple, but also quite important. Since imagine that if we crash at the middle of the write-to-disk commit operation. The header on disk won’t record the correct information of the file system.

The file system solving this problem by writing this special log

header log.hl into disk, which is

a copy of a single sector on disk, And one standard assumption

that file system make is that a single block write is an atomic

operation, meaning that if you write that, the whole sector

will be written or none of the sector will be written. (the sector will

never be written partially).

3. Install Transaction

After the commit, all logs are stored on disk (the log header, log sectors). We can now do the actual installation, which means write the actual transaction data into its sectors on disk.

install_trans() reads each block from the log in

disk and writes it to the proper place in the file system.

4. Clean Log

After all transactions have been written to the disk, we clear the

log number stored on disk.

(log.lh.n = 0).

v. Crash Recovery

This scheme is good because it actually ensures that no matter where a crash happends, we either install all the blocks of the writes or we install none of them. We’ll never end up in a situation where we installed some of the writes but not all of them.

The function recover_from_log is

responsible to recover the file system in case there are any crash

happends.

static void

recover_from_log(void)

{

read_head();

install_trans(1); // if committed, copy from log to disk

log.lh.n = 0;

write_head(); // clear the log

}- If a crash happends during step 1:

- If in

log_write, since we are not writing anything on disk at that time, all in memory. after the power off, all data in mem are gone, the file system will see nothing and that transaction will be treat as never happends before. - If in

write_log, since we haven’t write the log header into disk by callingwrite_head(we do not commit at that specific time).

- If in

- If a crash happends between step 1 and 2, The

recover_from_logwill see nothing in log header on disk (lh.n = 0) and will never write any data into disk. - If a crash happends between step 2 and 3. The

recover_from_logwill see the header block that indicates there are some data in log blocks (written bywrite_log()) and haven’t be written into its proper location on disk. After that, theinstall_transwill continue install the stopped transactions into disk.