4. Interrupts

04/03/2022 By Angold Wang

In the previous post, 3. Traps, we went through the actual xv6 code to illustrate the actual mechanics in the system call. I also mentioned at the begin of prev post, The “traps” mechanisim is used in 3 different situations: 1. System Call 2. Device Interrupt 3. Fault and Exceptions

Since the previous article covered the whole trap procedure (trampoline, recovery…) with actual xv6 code. Which is pretty much the same in these 3 situations. I’ll treat the “Trap” as an abstract procedure and this lecture will focus on things other than traps.

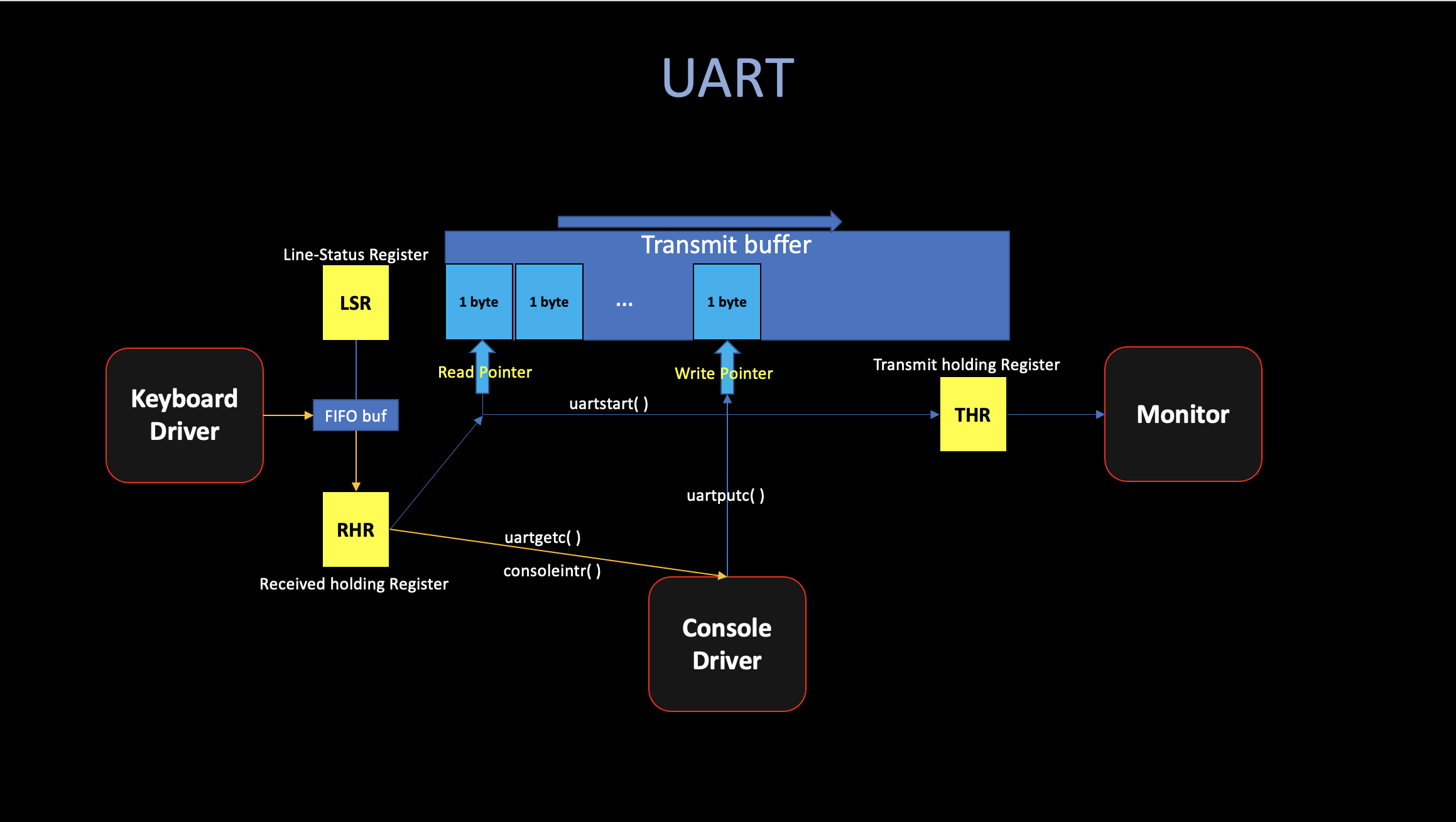

0. Device Driver (UART)

A driver is the code in an operating system that manages a particular device. Which: 1. Configures the device hardware. 2. Handles the resulting interrupts. 3. Tells the device to perform operations. 4. Interacts with processes that may be waiting for the I/O from the device.

While booting, xv6’s main calls

consoleinit to initialize the UART

hardware: * Generating a recieve interrupt when the

UART receives each byte of input. (In RHR) * Generating

a transmit complete interrupt each time the UART finishes sending a byte

of output. (In THR)

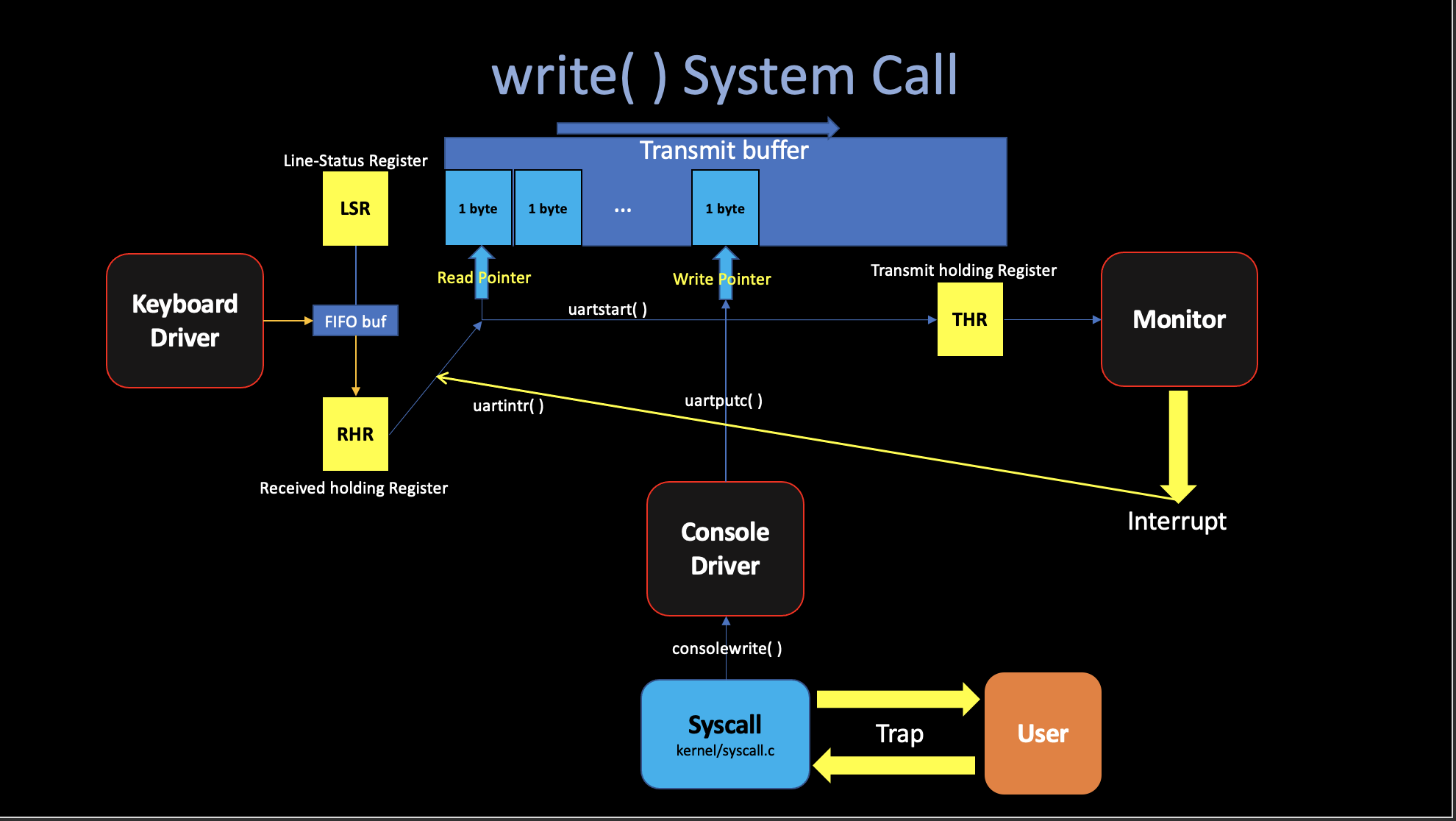

1. System Call

A system call will pause the current user-process, cause a trap which saves user’s current state… and jump to kernel space in order to execute the kernel syscall.

Let’s continue the actual write()

system call we mentioned last article. The way that shell indicate that

it is ready for user input is to print “$” in the console.

In the xv6 implementation, the shell calls fprintf

function, which will eventually make a system call

write(2, "$", 1).

fprintf(2, "$");Now we are in the kernel code, the write system call

eventually arrives at consolewrite()

located in kernel/console.c, which will write the stuff

byte-by-byte by calling uartputc(c).

Like I show in the figure, the UART device maintains an output buffer

(uart_tx_buf) so that writing processes do not have

to wait for the UART to finish sending, this mechanism, called

asynchrony, separates device activity from process

activity through buffering and

interrupts. Instead,

uartputc appends each character to the

buffer, kick the UART hardware to start transmitting by calling

uartstart().

Basically, uartstart() writes the byte

pointed to by the current write pointer into the THE, which

is the transmit holding register. In our system, once you write

that byte into THR, the UART hardware will send the data to

the Console (Monitor) to draw that byte on your monitor.

Each time UART finishes sending a byte to console, it generates an

interrupt. After the trap uartintr() calls

uartstart() again, which hands the device

the next buffered output character… It will keep that loop (the yellow

arrow showing on the figure) until no data in the buffer (writep ==

readp).

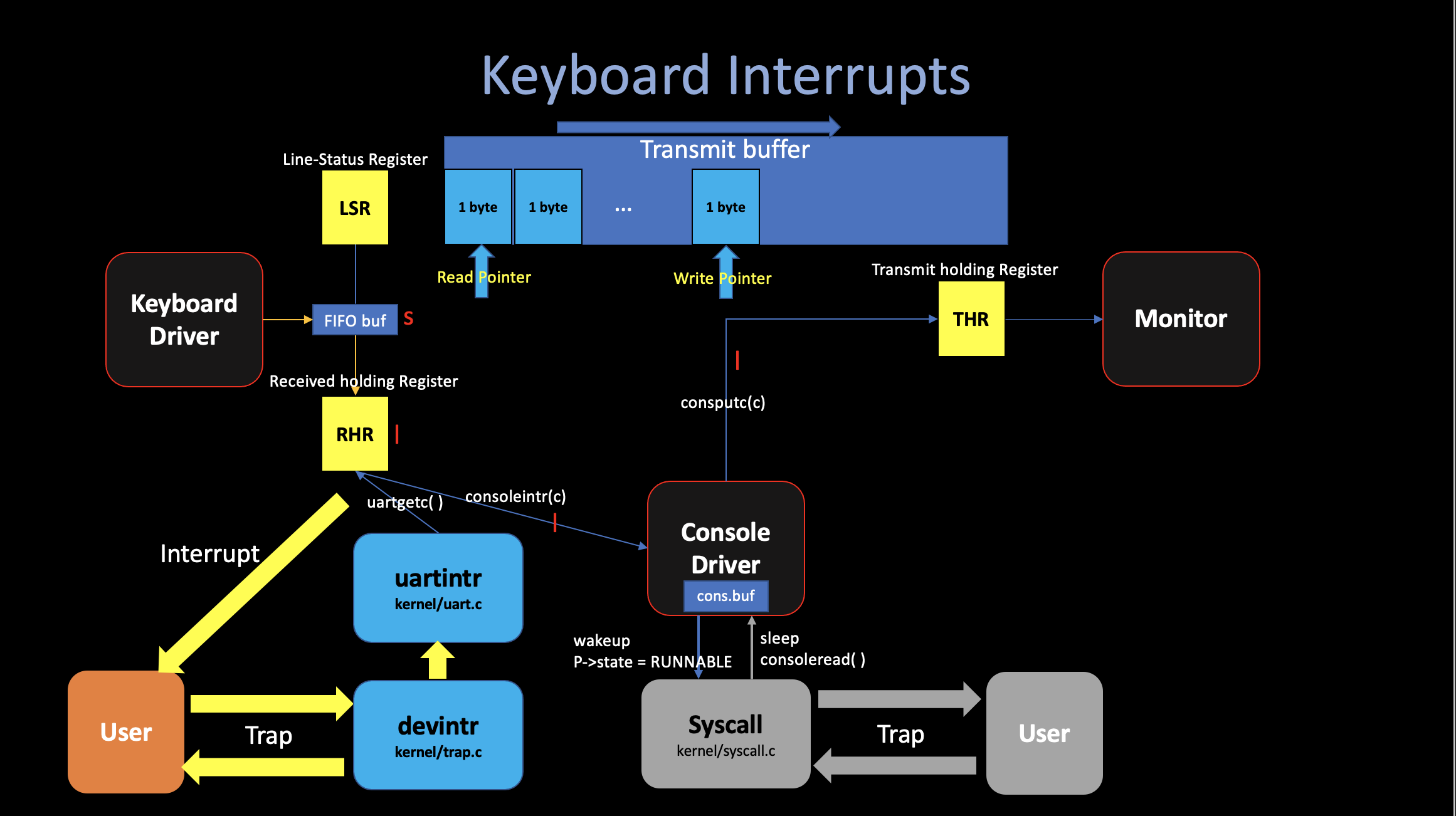

2. Device Interrupts

There are basically two kinds of device interrupts – The Timer interrupts and others.

i. Device interrupts

For the device interrups, typically, when a user types

“ls”, press enter in their keyboard and wants to pass

this command to the shell. The UART hardware asks the RISC=V to raise an

interrupt, The current user process will be interrupted and the xv6’s

trap handler will be activated. The trap handler calls

devintr (kernel/trap.c),

which looks at the RISC-V scause register to discover that

the interrupt is from an external device. Then it asks a hardware unit

called the PLIC to tell it which device interrupted. In

this case, it was the UART, devintr calls

uartintr.

uartintr reads any waiting input

characters from the UART hardware and hands them to

consoleintr, which accumulate

input characters in cons.buf until a whole line

arrives. The way is that

consoleintr treats backspace and a few

other characters specially. When a newline arrives, it wakes up a

waiting consoleread (if there is

one)(p->status = RUNNABLE), then back to the trap ret,

and resume the interrupted process.

Once woken, consoleread will observe a

full line in cons.buf, copy it to user space, and return

from the trap to the user space.

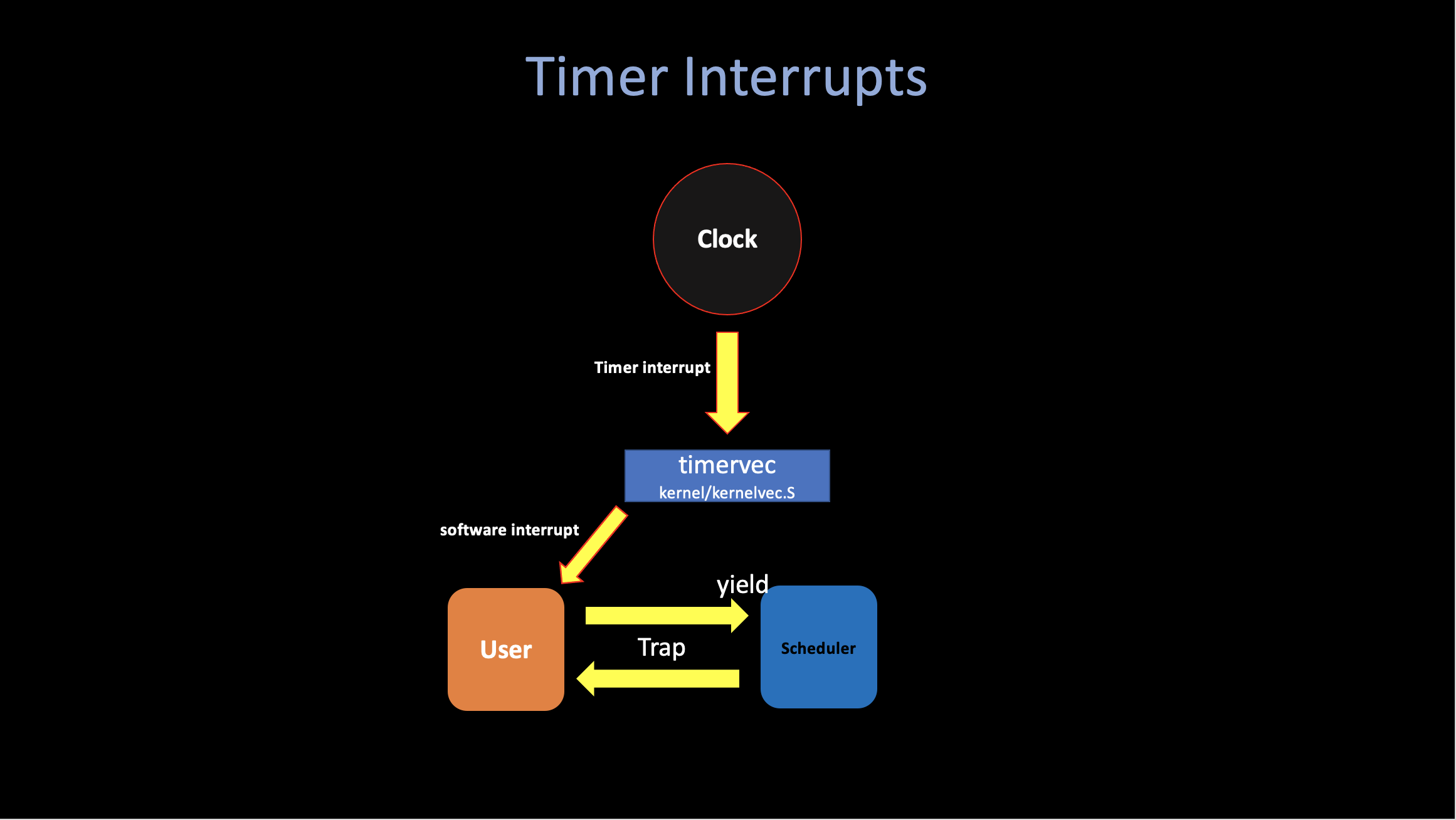

ii. Timer interrupts

Xv6 uses timer interrupts to switch among different compute-bound process.

The code timerinit in

kernel/start.c initializing the clock hardware. Basically,

it sets mtvec to timervec

(kernel/kernelvec.S) in order to deal with each clock interrupts.

A timer interrpt can occur at any point when user or kernel

code is executing. The basic strategy to handle a clock

interrupt is to ask the RISC-V to raise a “software

interrupt” and then immediately return (then switch to

the sheduler’s context by calling yield() which we

will talk in great amount of details next post). The RISC-V delivers

software interrupts to the kernel with the ordinary trap

mechanism, and allows the kernel to disable them (very

important for code executing in critical section).

The xv6 makes sure that there will always be an interrupt while the code executing in the user space.

3. Fault and Exceptions

Xv6’s response to exceptions is quite boring: * If an exception happens in user space, the kernel kills the faulting process. * If an exception happens in the kernel, the kernel panics.

In the real sophisticated operating system, fault and exceptions often be responded in much more interesting ways.

i. Copy-on-Write

The problem

The fork() system call in xv6 copies all of the parent

process’s user-space memory into the child. If the parent is large,

copying can take a long time. Worse, the work is often largely wasted;

for example, a fork() followed by exec() in

the child will cause the child to discard the copied memory, probably

without ever using most of it. On the other hand, if both parent and

child use a page, and one or both writes it, a copy is truly needed.

The solution

The goal of copy-on-write (COW) fork() is to defer

allocating and copying physical memory pages for the child until the

copies are actually needed, if ever. COW fork() creates

just a pagetable for the child, with PTEs for user memory pointing to

the parent’s physical pages. COW fork() marks all the user

PTEs in both parent and child as not writable.

When either process tries to write one of these COW pages, the CPU will force a page fault. The kernel page-fault handler detects this case, allocates a page of physical memory for the faulting process, copies the original page into the new page, and modifies the relevant PTE in the faulting

process to refer to the new page, this time with the PTE marked writeable. When the page fault handler returns, the user process will be able to write its copy of the page.

6.S081 Lab6 Copy-on-write fork

ii. Lazy Allocation

One of the many neat tricks an O/S can play with page table hardware is lazy allocation of user-space heap memory.

Xv6 applications ask the kernel for heap memory using the

sbrk() system call. In the kernel we’ve given you,

sbrk() allocates physical memory and maps it into the

process’s virtual address space. It can take a long time for a kernel to

allocate and map memory for a large request. Consider, for example, that

a gigabyte consists of 262,144 4096-byte pages; that’s a

huge number of allocations even if each is individually cheap.

In addition, some programs allocate more memory than they actually

use (e.g., to implement sparse arrays), or allocate memory well in

advance of use. To allow sbrk() to complete more quickly in

these cases, sophisticated kernels allocate user memory lazily. That is,

sbrk() doesn’t allocate physical memory, but just remembers

which user addresses are allocated and marks those addresses as invalid

in the user page table.

When the process first tries to use any given page of lazily-allocated memory, the CPU generates a page fault, which the kernel handles by allocating physical memory, zeroing it, and mapping it.