3. Special Topic: Traps

03/06/2022 By Angold Wang

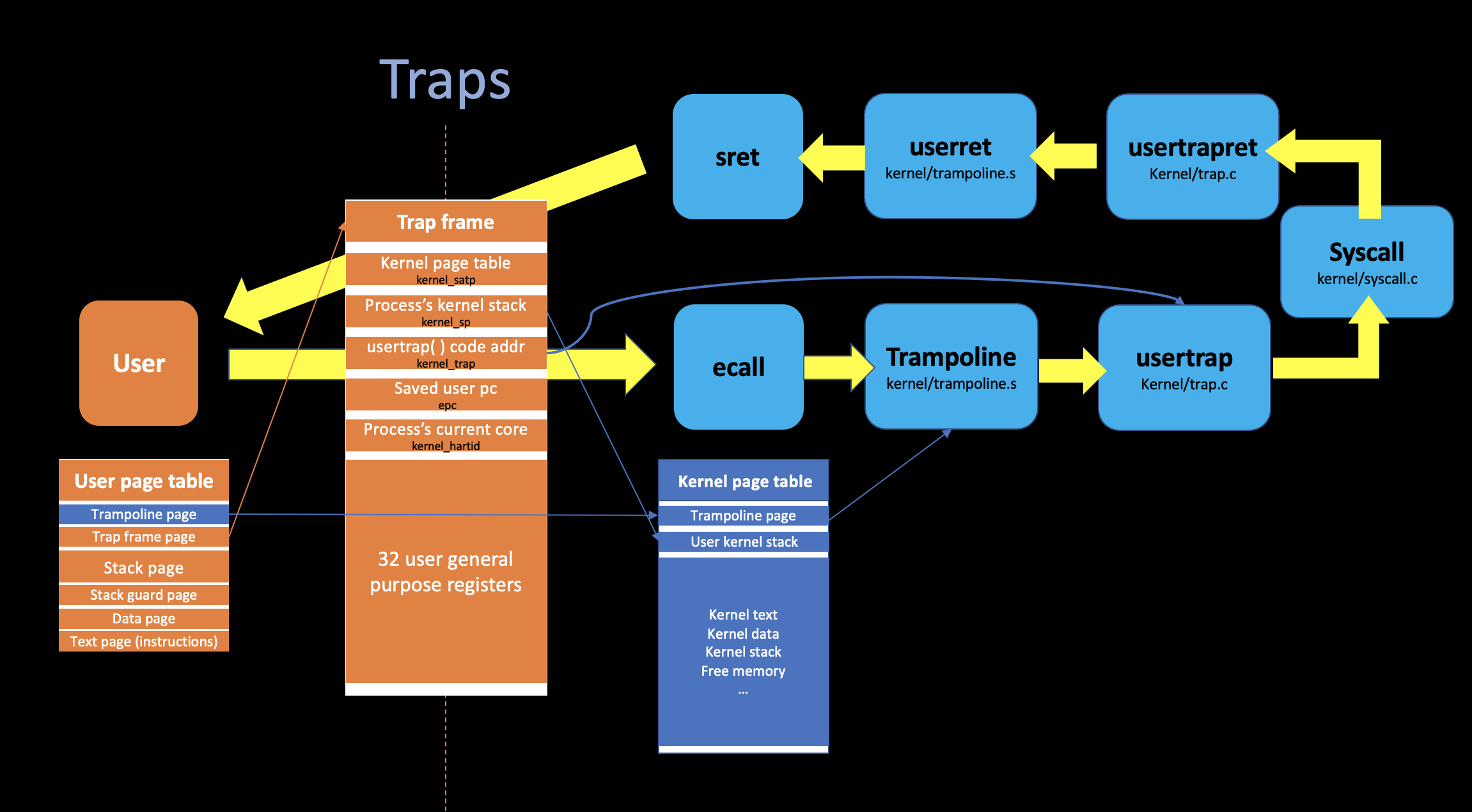

There are three kinds of event which cause the CPU to set aside

ordinary execution of instructions and force a transfer of control to

special code that handles the event: 1. System Call:

When a user program executes the ecall

instruction to ask the kernel to do something for it. 2.

Exception: When an instruction (user/kernel) does

something illegal, such as divide by zero or use an invalid virtual

address, or page fault. 3. Interrupt: When a device

signals that it needs attention.

Trap is a generic term for these situations. Typically, whatever code was executing at the time of the trap will later need to resume, and shouldn’t need to be aware that anything special happends.

In this topic, we’ll step into the actual xv6

code and check the details of how traps were implemented by walking

through a whole SYS_write system call procedule when we

booting the xv6.

0. Boot xv6

When the RISC-V computer powers on. It initializes itself and runs a boot loader which is stored in read-only memory. The boot loader loads the xv6 kernel into memory.

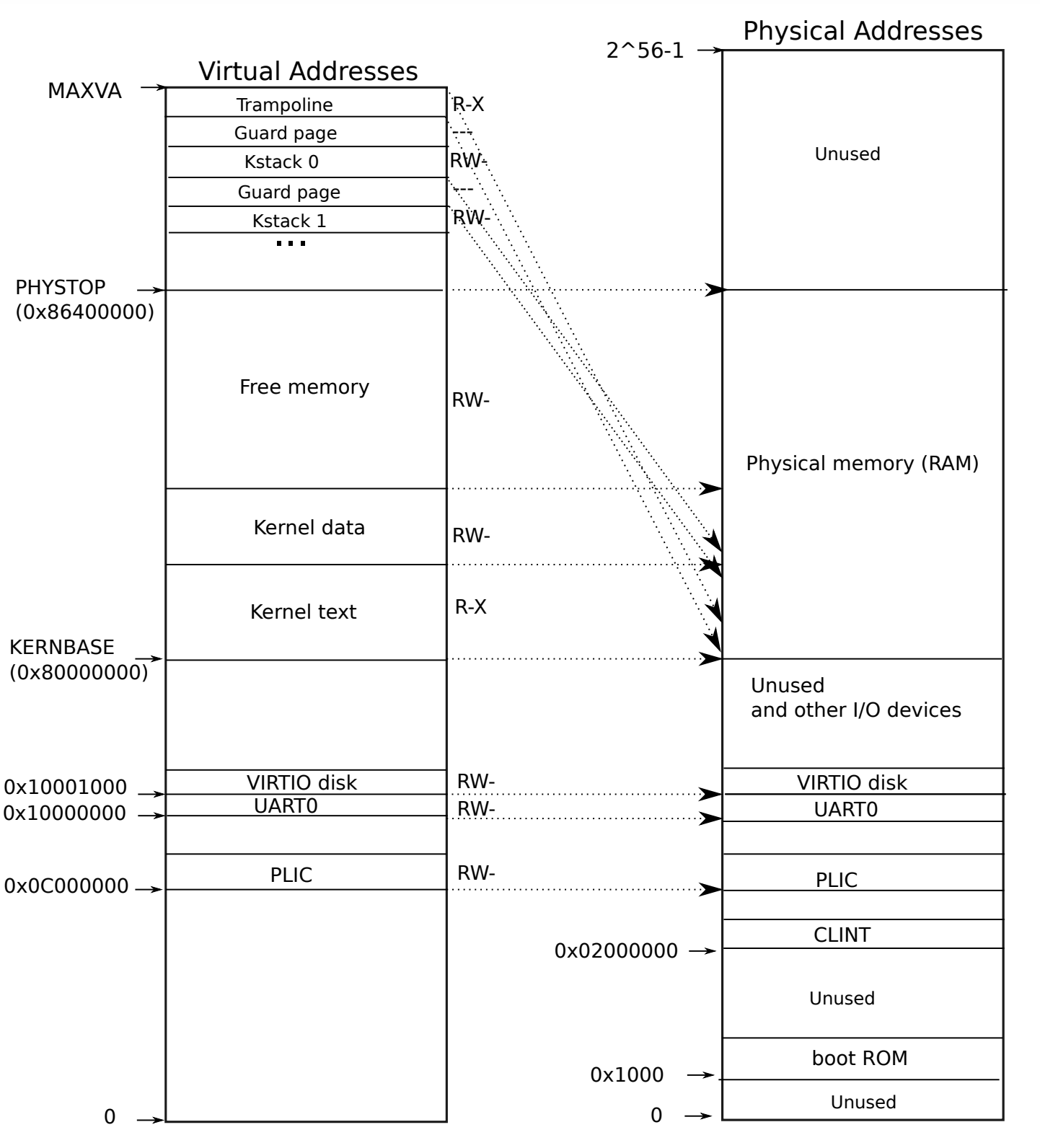

The loader loads the xv6 kernel into memory at physical address

0x80000000. The reason it places the

kernel at 0x80000000 rather than

0x0 is because the address range

0x0:0x80000000 contains I/O devices.

i. _entry

Then in machine mode. The CPU executes xv6 starting

at _entry (kernel/entry.s)

# qemu -kernel loads the kernel at 0x80000000

# and causes each CPU to jump there.

# kernel.ld causes the following code to

# be placed at 0x80000000.

.section .text

.global _entry

_entry:

# set up a stack for C.

# stack0 is declared in start.c,

# with a 4096-byte stack per CPU.

# sp = stack0 + (hartid * 4096)

la sp, stack0

li a0, 1024*4

csrr a1, mhartid

addi a1, a1, 1

mul a0, a0, a1

add sp, sp, a0

# jump to start() in start.c

call start

spin:

j spinBasically, this piece of code does two things:

- Set up a stack so that xv6 can run C code. and set the stack

pointer

%spwith the addressstack0 + 4096.- Set the stack in order to let xv6 run C code

- The

stack0is defined inkernel/start.c, which is the initial stack of xv6.

- Then calls into C code at

startatkernel/start.c

ii. start

// entry.S jumps here in machine mode on stack0.

void

start()

{

// set M Previous Privilege mode to Supervisor, for mret.

unsigned long x = r_mstatus();

x &= ~MSTATUS_MPP_MASK;

x |= MSTATUS_MPP_S;

w_mstatus(x);

// set M Exception Program Counter to main, for mret.

// requires gcc -mcmodel=medany

w_mepc((uint64)main);

// disable paging for now.

w_satp(0);

// delegate all interrupts and exceptions to supervisor mode.

w_medeleg(0xffff);

w_mideleg(0xffff);

w_sie(r_sie() | SIE_SEIE | SIE_STIE | SIE_SSIE);

// configure Physical Memory Protection to give supervisor mode

// access to all of physical memory.

w_pmpaddr0(0x3fffffffffffffull);

w_pmpcfg0(0xf);

// ask for clock interrupts.

timerinit();

// keep each CPU's hartid in its tp register, for cpuid().

int id = r_mhartid();

w_tp(id);

// switch to supervisor mode and jump to main().

asm volatile("mret");

}Machine Mode vs. Supervisor Mode: Machine mode has access to all the hardware features but does not have virtual-memory support.

- Writing

main’s address into register%mepcin order to return tomainafterstartfinished - Writing

0into the page-table registersatpin order to disables virtual address translation (we haven’t set the page table yet). - Program the clock chip to generate clock interrupt (0.1s).

Although we haven’t set any page table yet (even for kernel page

table), we still can access some physical memory. The reason is that

“Identical Mapping” in xv6, which mapping the

resources at virtual address between 0x80000000 to

0x86400000 that are equal to the physical

address.

iii. main

// start() jumps here in supervisor mode on all CPUs.

void

main()

{

if(cpuid() == 0){

consoleinit();

printfinit();

printf("\n");

printf("xv6 kernel is booting\n");

printf("\n");

kinit(); // physical page allocator

kvminit(); // create kernel page table

kvminithart(); // turn on paging

procinit(); // process table

trapinit(); // trap vectors

trapinithart(); // install kernel trap vector

plicinit(); // set up interrupt controller

plicinithart(); // ask PLIC for device interrupts

binit(); // buffer cache

iinit(); // inode table

fileinit(); // file table

virtio_disk_init(); // emulated hard disk

userinit(); // first user process

__sync_synchronize();

started = 1;

} else {

while(started == 0)

;

__sync_synchronize();

printf("hart %d starting\n", cpuid());

kvminithart(); // turn on paging

trapinithart(); // install kernel trap vector

plicinithart(); // ask PLIC for device interrupts

}

scheduler();

}This is the main() boot sequence of xv6, We are

going to only introduce two procedures since we only mentioned these two

concepts before. * kvminit() for

initializing kernel page table *

userinit() for making the first user system

call

iv. main –

kvminit()

// Initialize the one kernel_pagetable

void

kvminit(void)

{

kernel_pagetable = kvmmake();

}main calls kvminit to create the

kernel’s page table using kvmmake, this call occurs before

xv6 has enabled paging on the RISC-V, so the address refer directly to

physical memory.

// Make a direct-map page table for the kernel.

pagetable_t

kvmmake(void)

{

pagetable_t kpgtbl;

kpgtbl = (pagetable_t) kalloc();

memset(kpgtbl, 0, PGSIZE);

// uart registers

kvmmap(kpgtbl, UART0, UART0, PGSIZE, PTE_R | PTE_W);

// virtio mmio disk interface

kvmmap(kpgtbl, VIRTIO0, VIRTIO0, PGSIZE, PTE_R | PTE_W);

// PLIC

kvmmap(kpgtbl, PLIC, PLIC, 0x400000, PTE_R | PTE_W);

// map kernel text executable and read-only.

kvmmap(kpgtbl, KERNBASE, KERNBASE, (uint64)etext-KERNBASE, PTE_R | PTE_X);

// map kernel data and the physical RAM we'll make use of.

kvmmap(kpgtbl, (uint64)etext, (uint64)etext, PHYSTOP-(uint64)etext, PTE_R | PTE_W);

// map the trampoline for trap entry/exit to

// the highest virtual address in the kernel.

kvmmap(kpgtbl, TRAMPOLINE, (uint64)trampoline, PGSIZE, PTE_R | PTE_X);

// map kernel stacks

proc_mapstacks(kpgtbl);

return kpgtbl;

}kvmmakefirst allocates a page of physical memory to hold the root page-table page.- Then it calls

kvmmapto install the translations(page tables) that the kernel needs:- kernel’s instructions and data.

- physical memory up to

PHYSTOP - memory ranges which are actually devices

- Finially it calls

proc_mapstacksin order to allocate a kernel stack for each process.

- After all these mappings are done, the kernel’s page table should looks like this:

(qemu) info mem

vaddr paddr size attr

---------------- ---------------- ---------------- -------

000000000c000000 000000000c000000 0000000000400000 rw-----

0000000010000000 0000000010000000 0000000000002000 rw-----

0000000080000000 0000000080000000 0000000000001000 r-x--a-

0000000080001000 0000000080001000 0000000000007000 r-x----

0000000080008000 0000000080008000 0000000000017000 rw-----

000000008001f000 000000008001f000 0000000000001000 rw---a-

0000000080020000 0000000080020000 0000000007fe0000 rw-----

0000003ffff7f000 0000000087f78000 0000000000040000 rw-----

0000003ffffff000 0000000080007000 0000000000001000 r-x----

// add a mapping to the kernel page table.

// only used when booting.

// does not flush TLB or enable paging.

void

kvmmap(pagetable_t kpgtbl, uint64 va, uint64 pa, uint64 sz, int perm)

{

if(mappages(kpgtbl, va, sz, pa, perm) != 0)

panic("kvmmap");

}

// Create PTEs for virtual addresses starting at va that refer to

// physical addresses starting at pa. va and size might not

// be page-aligned. Returns 0 on success, -1 if walk() couldn't

// allocate a needed page-table page.

int

mappages(pagetable_t pagetable, uint64 va, uint64 size, uint64 pa, int perm)

{

uint64 a, last;

pte_t *pte;

if(size == 0)

panic("mappages: size");

a = PGROUNDDOWN(va);

last = PGROUNDDOWN(va + size - 1);

for(;;){

if((pte = walk(pagetable, a, 1)) == 0)

return -1;

if(*pte & PTE_V)

panic("mappages: remap");

*pte = PA2PTE(pa) | perm | PTE_V;

if(a == last)

break;

a += PGSIZE;

pa += PGSIZE;

}

return 0;

}kvmmap calls mappages, which

installs mappings into a page table for a range of virtual addresses to

a corresponding range of physical addresses. It does this

seperately for each virtual address in the range, at page intervals. For

each virtual address to be mapped,

mappages calls

walk to find the address of the PTE for

that address. It then initializes the PTE to hold the relevant physical

page number, and set its desired permissions.

Basically, what the mappages does is that it

creates many page tables by calling walk, in order to map

size of memory from virtual address va to

physical address pa.

// Return the address of the PTE in page table pagetable

// that corresponds to virtual address va. If alloc!=0,

// create any required page-table pages.

//

// The risc-v Sv39 scheme has three levels of page-table

// pages. A page-table page contains 512 64-bit PTEs.

// A 64-bit virtual address is split into five fields:

// 39..63 -- must be zero.

// 30..38 -- 9 bits of level-2 index.

// 21..29 -- 9 bits of level-1 index.

// 12..20 -- 9 bits of level-0 index.

// 0..11 -- 12 bits of byte offset within the page.

pte_t *

walk(pagetable_t pagetable, uint64 va, int alloc)

{

if(va >= MAXVA)

panic("walk");

for(int level = 2; level > 0; level--) {

//

// PX extract the three 9-bit page table indices from a virtual address.

pte_t *pte = &pagetable[PX(level, va)];

if(*pte & PTE_V) { // valid or not

pagetable = (pagetable_t)PTE2PA(*pte);

} else {

if(!alloc || (pagetable = (pde_t*)kalloc()) == 0)

return 0;

memset(pagetable, 0, PGSIZE);

*pte = PA2PTE(pagetable) | PTE_V;

}

}

return &pagetable[PX(0, va)]; // the new page table

}Finally comes to walk, this function mimics the

RISC-V paging hardware as it looks up the PTE for a virtual

address. 1. walk descends the

3-level page table 9 bits at the time. It uses each level’s 9 bits of

virtual address to find the PTE of either the next-level page table or

the final page table. 2. If the PTE isn’t valid, then the required page

hasn’t yet been allocated; if the alloc argument is set,

walk allocates a new page-table page and

puts its physical address in the PTE. 3. Finally, it returns the address

of the PTE in the lowest layer in the tree.

After all page tables of kernel has been created successfully,

main calls

kvminithart, which install this kernel

page table by writing the physical address of the root page table page

into the register satp, and then allow CPU translate

addresses using the kernel page table.

// Switch h/w page table register to the kernel's page table,

// and enable paging.

void

kvminithart()

{

w_satp(MAKE_SATP(kernel_pagetable));

sfence_vma();

}v. main –

userinit()

After main initializes several devices,

subsystems and memory, it create the first user process by calling

userinit.

// a user program that calls exec("/init")

// od -t xC initcode

uchar initcode[] = {

0x17, 0x05, 0x00, 0x00, 0x13, 0x05, 0x45, 0x02,

0x97, 0x05, 0x00, 0x00, 0x93, 0x85, 0x35, 0x02,

0x93, 0x08, 0x70, 0x00, 0x73, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x93, 0x08, 0x20, 0x00, 0x73, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0xef, 0xf0, 0x9f, 0xff, 0x2f, 0x69, 0x6e, 0x69,

0x74, 0x00, 0x00, 0x24, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

};

// Set up first user process.

void

userinit(void)

{

struct proc *p;

// Look in the process table for an UNUSED proc.

p = allocproc(); // total 64 process,

initproc = p;

// allocate one user page and copy init's instructions

// and data into it.

uvminit(p->pagetable, initcode, sizeof(initcode));

p->sz = PGSIZE;

// prepare for the very first "return" from kernel to user.

p->trapframe->epc = 0; // user program counter

p->trapframe->sp = PGSIZE; // user stack pointer

safestrcpy(p->name, "initcode", sizeof(p->name));

p->cwd = namei("/");

p->state = RUNNABLE;

release(&p->lock);

}userinit basically does these things:

1. It look in the process table for an unused proc by calling

allocproc 2. Call

uvminit to set the user virtual memory,

and load the initcode into the new process’s page table in

order to exec. 3. Set the first user process’s state to

RUNNABLE, which means it will assigned to be executed by

process scheduler.

# initcode.s

# Initial process that execs /init.

# This code runs in user space.

#include "syscall.h"

# exec(init, argv)

.globl start

start:

la a0, init

la a1, argv

li a7, SYS_exec

ecall

# for(;;) exit();

exit:

li a7, SYS_exit

ecall

jal exit

# char init[] = "/init\0";

init:

.string "/init\0"

# char *argv[] = { init, 0 };

.p2align 2

argv:

.long init

.long 0

initcode.s (user/initcode.S) loads the

number for the exec system call, SYS_EXEC into

register a7, and then calls ecall to re-enter

the kernel in order to execute exec system call. The

details of this procedure is what we will discuss in detail later

on.

After the kernel has completed exec by replacing the

page table and registers of the current process. it return to user space

in the /init process (execute it).

init creates a new console device

file (console is the text entry and display device for system

administration messages) and then opens it as file descriptors 0, 1, and

2. Then it starts a shell on the console. The system is up.

// init.c

// init: The initial user-level program

char *argv[] = { "sh", 0 };

int

main(void)

{

int pid, wpid;

if(open("console", O_RDWR) < 0){

mknod("console", CONSOLE, 0);

open("console", O_RDWR);

}

dup(0); // stdout

dup(0); // stderr

for(;;){

printf("init: starting sh\n");

pid = fork();

if(pid < 0){

printf("init: fork failed\n");

exit(1);

}

if(pid == 0){

exec("sh", argv);

printf("init: exec sh failed\n");

exit(1);

}

for(;;){

// this call to wait() returns if the shell exits,

// or if a parentless process exits.

wpid = wait((int *) 0);

if(wpid == pid){

// the shell exited; restart it.

break;

} else if(wpid < 0){

printf("init: wait returned an error\n");

exit(1);

} else {

// it was a parentless process; do nothing.

}

}

}

}1. ecall

i. User-level process

The kernel must allocate and free physical memory at run-time

for page tables, user memory, kernel stacks and pipe buffers.

xv6 uses the physical memory between the end of the kernel and

PHYSTOP for run-time allocation, as we can see in the

layout figure (va & pa) located near the begin of this note, these

area are not the part of direct mapping.

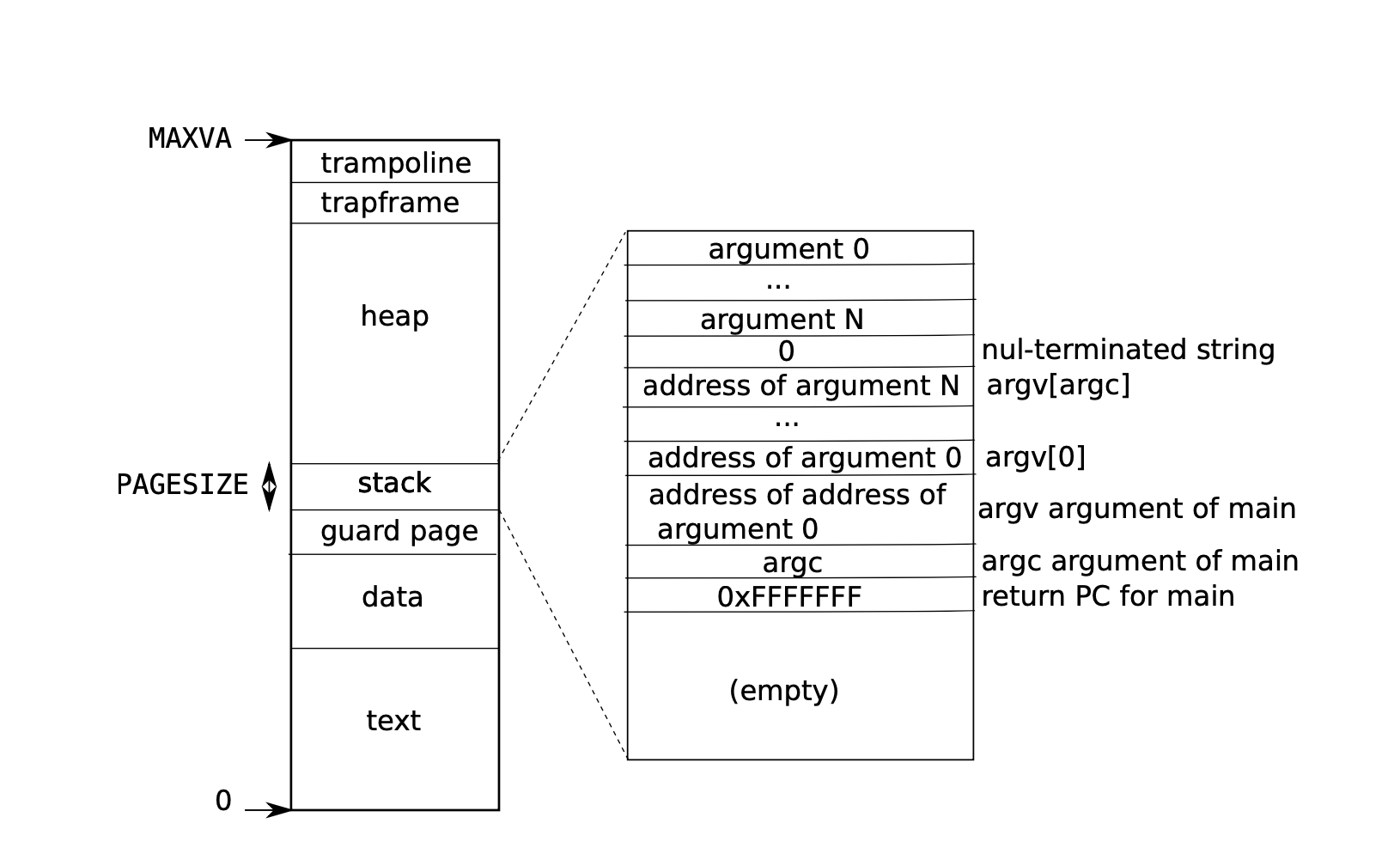

Each process has a separate page table. the figure below shows the

layout of the user memory of an executing process in

xv6. Notice that the stack is a single page, and is shown with the

initial contents as created by exec, where contains the

command-line arguments, as well as an array of pointers at the very top

of the stack.

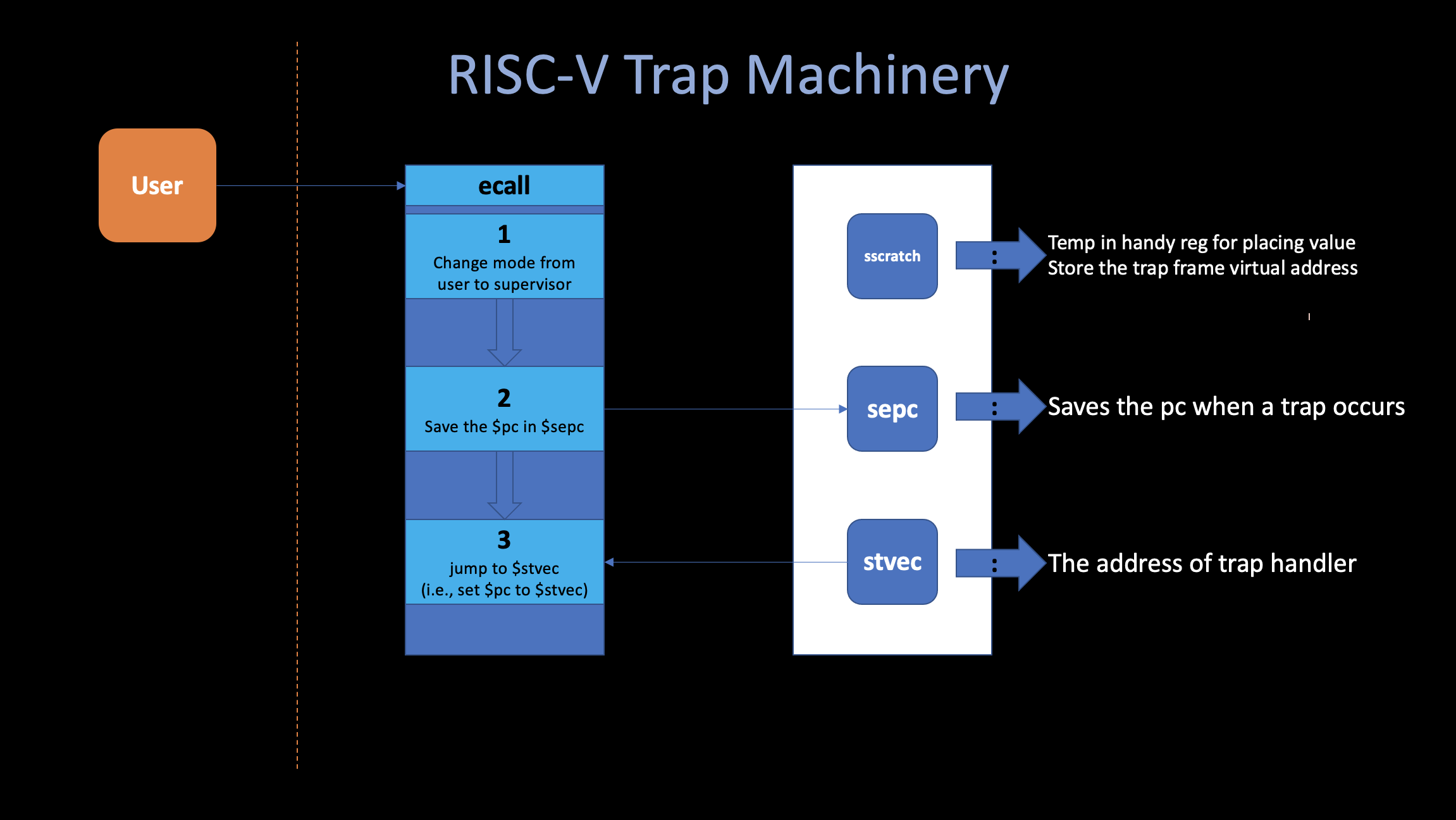

ii. RISC-V trap machinery

Each RISC-V CPU has a set of control registers that the

kernel writes to tell the CPU how to handle traps, and that the kernel

can read to find out about a trap that has occured. Here is an

outline of the most important registers:

$sscratch,

$stvec and

$sepc:

iii. Traps from user space

After init starts the shell, the shell

(user/sh.c) will call getcmd and trying to

receive a command from user. getcmd will call

fprintf defined in user/printf.c in order to

print $ at the console.

If you jump into the fprintf code located in

user/printf.c, since the shell runs in the user-space, it

require a write system call in order to print anything to

the console.

// user/printf.c

static void

putc(int fd, char c)

{

write(fd, &c, 1);

}After calling that write in user space, the

write function which sit in the shell library will cause a

trap:

# user/sh.asm

0000000000000de8 <write>:

.global write

write:

li a7, SYS_write

de8: 48c1 li a7,16

ecall

dea: 00000073 ecall

ret

dee: 8082 retA trap may occur while executing in user space if the user program

makes a system call (ecall instruction). And the

ecall basically did three things: 1.

Change mode from user to supervisor. 2. Save

$pc in $sepc. 3. Jump to

$stvec.

Now lets jump into the runtime of shell when it prints

$ which causes the write system call for the

first time:

(gdb) b *0xdea

Breakpoint 1 at 0xdea

(gdb) c

Continuing.

Breakpoint 1, 0x0000000000000dea in ?? ()

=> 0x0000000000000dea: 73 00 00 00 ecall

(gdb) x/3i 0xde8

0xde8: li a7,16

=> 0xdea: ecall

0xdee: retAnd we can check the current $pc and page table

of our shell process:

(gdb) print $pc

$1 = (void (*)()) 0xdea

(qemu) info mem

vaddr paddr size attr

---------------- ---------------- ---------------- -------

0000000000000000 0000000087f61000 0000000000001000 rwxu-a-

0000000000001000 0000000087f5e000 0000000000001000 rwxu-a-

0000000000002000 0000000087f5d000 0000000000001000 rwx----

0000000000003000 0000000087f5c000 0000000000001000 rwxu-ad

0000003fffffe000 0000000087f70000 0000000000001000 rw---ad

0000003ffffff000 0000000080007000 0000000000001000 r-x--a-As you can see that, this is a very small page table that

contains only six mappings, if you check that user-level process memory

layout figure above, from top to bottom: *

0x0000000000000000 to

0x0000000000001000 refers to the shell’s instructions

(text). * 0x0000000000001000 to

0x0000000000002000 refers to the shell’s data. *

0x0000000000002000 to

0x0000000000003000 refers to the stack guard page

* which is invalid, since it doesn’t have the u flag set. *

the user code can only get at pte entries for which the u

flag is set. * 0x0000000000003000 to

0x0000000000004000 refers to the stack page, which can grow

dynamically. * 0x0000003fffffe000 to

0x0000003ffffff000 refers to the trap frame page.

* 0x0000003ffffff000 to

0x0000004000000000 refers to the trampoline

page.

Now let’s step further, and execute that ecall

instruction:

(gdb) stepi

0x0000003ffffff000 in ?? ()

=> 0x0000003ffffff000: 73 15 05 14 csrrw a0,sscratch,a0

(gdb) print $pc

$2 = (void (*)()) 0x3ffffff000

(gdb) x/6i 0x3ffffff000

=> 0x3ffffff000: csrrw a0,sscratch,a0

0x3ffffff004: sd ra,40(a0)

0x3ffffff008: sd sp,48(a0)

0x3ffffff00c: sd gp,56(a0)

0x3ffffff010: sd tp,64(a0)

0x3ffffff014: sd t0,72(a0)As we can see, the value $stvec register is the

current $pc register value, which is the begining of

trampoline page. And that is the reason why we ended up executing at

this particular place.

(gdb) print/x $stvec

$4 = 0x3ffffff000

(gdb) print/x $sepc

$5 = 0xdea

(gdb) print/x $sscratch

$6 = 0x3fffffe000Another thing is we can see is that the ecall

hardware instruction has already helped us storing the previous

$pc into $sepc.

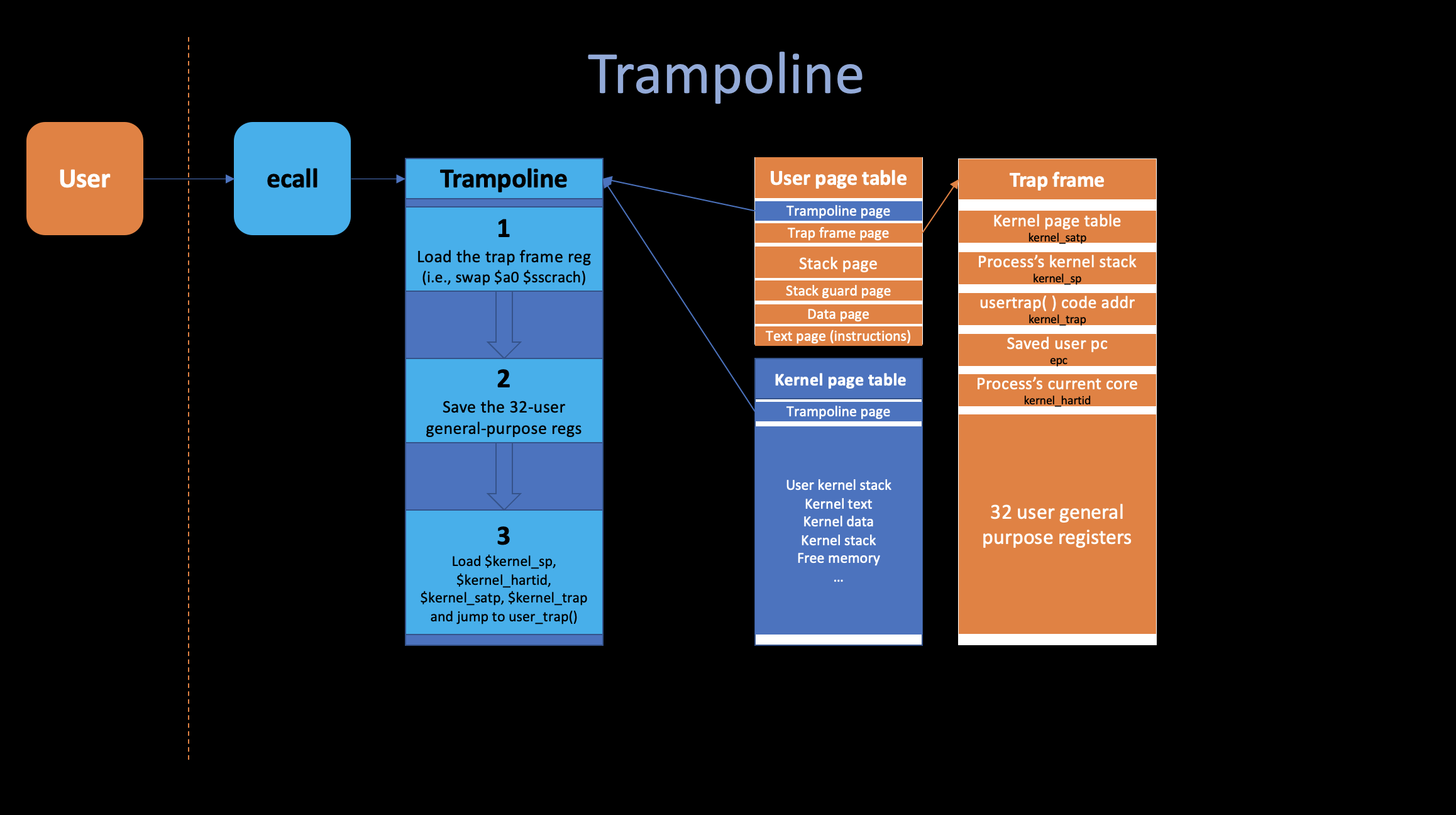

2. Trampoline

We’re now executing in the “trampoline” page, which contains

the start of the kernel’s trap handling code,

ecall does as little as possible to allow maximum

flexibility to the operating system programmer to design the os however

they like.

What need to happen now? * Save the 32 user register values. (so we can later restore them and when we want to resume the user code) * we need to save those registers because we are going to run C code inside kernel, which will use all these registers. * Switch to the kernel page table. * Set up stack for kernel C code. * Jump to some sensible place in the C code in the kernel.

i. The Trap frame

- We don’t even know the address of the kernel page table

- We need some spare registers in order to execute change

$satpinstruction.

The xv6 maps a page, called trapframe into every user page table, it has space to to hold the saved registers, the kernel gives each process a different trapframe page.

The virtual address of that trapframe is stored in the

$sscrach register, and you can find the

struct trapframe in kernel/proc.h.

// per-process data for the trap handling code in trampoline.S.

// sits in a page by itself just under the trampoline page in the

// user page table. not specially mapped in the kernel page table.

// the sscratch register points here.

// uservec in trampoline.S saves user registers in the trapframe,

// then initializes registers from the trapframe's

// kernel_sp, kernel_hartid, kernel_satp, and jumps to kernel_trap.

// usertrapret() and userret in trampoline.S set up

// the trapframe's kernel_*, restore user registers from the

// trapframe, switch to the user page table, and enter user space.

// the trapframe includes callee-saved user registers like s0-s11 because the

// return-to-user path via usertrapret() doesn't return through

// the entire kernel call stack.

struct trapframe {

/* 0 */ uint64 kernel_satp; // kernel page table

/* 8 */ uint64 kernel_sp; // top of process's kernel stack

/* 16 */ uint64 kernel_trap; // usertrap()

/* 24 */ uint64 epc; // saved user program counter

/* 32 */ uint64 kernel_hartid; // saved kernel tp

/* 40 */ uint64 ra;

/* 48 */ uint64 sp;

/* 56 */ uint64 gp;

/* 64 */ uint64 tp;

/* 72 */ uint64 t0;

/* 80 */ uint64 t1;

/* 88 */ uint64 t2;

/* 96 */ uint64 s0;

/* 104 */ uint64 s1;

/* 112 */ uint64 a0;

/* 120 */ uint64 a1;

/* 128 */ uint64 a2;

/* 136 */ uint64 a3;

/* 144 */ uint64 a4;

/* 152 */ uint64 a5;

/* 160 */ uint64 a6;

/* 168 */ uint64 a7;

/* 176 */ uint64 s2;

/* 184 */ uint64 s3;

/* 192 */ uint64 s4;

/* 200 */ uint64 s5;

/* 208 */ uint64 s6;

/* 216 */ uint64 s7;

/* 224 */ uint64 s8;

/* 232 */ uint64 s9;

/* 240 */ uint64 s10;

/* 248 */ uint64 s11;

/* 256 */ uint64 t3;

/* 264 */ uint64 t4;

/* 272 */ uint64 t5;

/* 280 */ uint64 t6;

};ii. The Trampoline

After ecall, as we mentioned before, the

hardware set $pc to $stvec, which is the

begining of the trapoline page.

The first instruction, csrrw. swap $a0

register and $sscratch, as we can see, after executing this

very first instruction, the $a0 becomes

0x3fffffe000, which is the begining of the trap page. And

$sscratch is 2, which is the first argument of this

write system call – the file descriptor 2.

(gdb) print/x $a0

$1 = 0x3fffffe000

(gdb) print $sscratch

$2 = 2The very next 32 sd instructions in this trampoline

code, store every 64-bit register to a different offset in the trap

frame page.

.globl trampoline

trampoline:

.align 4

.globl uservec

uservec:

#

# trap.c sets stvec to point here, so

# traps from user space start here,

# in supervisor mode, but with a

# user page table.

#

# sscratch points to where the process's p->trapframe is

# mapped into user space, at TRAPFRAME.

#

# swap a0 and sscratch

# so that a0 is TRAPFRAME

csrrw a0, sscratch, a0

# save the user registers in TRAPFRAME

sd ra, 40(a0)

sd sp, 48(a0)

sd gp, 56(a0)

sd tp, 64(a0)

sd t0, 72(a0)

sd t1, 80(a0)

sd t2, 88(a0)

sd s0, 96(a0)

sd s1, 104(a0)

sd a1, 120(a0)

sd a2, 128(a0)

sd a3, 136(a0)

sd a4, 144(a0)

sd a5, 152(a0)

sd a6, 160(a0)

sd a7, 168(a0)

sd s2, 176(a0)

sd s3, 184(a0)

sd s4, 192(a0)

sd s5, 200(a0)

sd s6, 208(a0)

sd s7, 216(a0)

sd s8, 224(a0)

sd s9, 232(a0)

sd s10, 240(a0)

sd s11, 248(a0)

sd t3, 256(a0)

sd t4, 264(a0)

sd t5, 272(a0)

sd t6, 280(a0)

# save the user a0 in p->trapframe->a0

csrr t0, sscratch

sd t0, 112(a0)

# restore kernel stack pointer from p->trapframe->kernel_sp

ld sp, 8(a0)

# make tp hold the current hartid, from p->trapframe->kernel_hartid

ld tp, 32(a0)

# load the address of usertrap(), p->trapframe->kernel_trap

ld t0, 16(a0)

# restore kernel page table from p->trapframe->kernel_satp

ld t1, 0(a0)

csrw satp, t1

sfence.vma zero, zero

# a0 is no longer valid, since the kernel page

# table does not specially map p->tf.

# jump to usertrap(), which does not return

jr t0After save those 32 general-purpose registers, we need to restore

some important register by execute ld instrucions, which

will be used in the kernel space later on.

Process’s kernel stack pointer

(gdb) print/x $sp

$5 = 0x3fffffc000The process’s kernel stack is up in high memory, because xv6 treats kernel stack especially so that it can put a guard page under each kernel stack.

Process’s current core

(gdb) print/x $tp

$6 = 0x0Since there is no direct way in RISC-V to figure out which of the

multiple cores you’re running on, xv6 actually keeps the core number

called kernel_hartid in the $tp register.

User trap

(gdb) print/x $t0

$7 = 0x80001c38Then we load the user trap c function address into $t0,

which we’ll jump to that location later on.

Kernel page table

(gdb) print/x $satp

$8 = 0x8000000000087fffAs soon as the ld and csrw

instruction executes, we’ll switch page table from the user page table

to kernel page table, after these instructions finished, we can see now

we are in the kernel page table. And now we are pretty much

ready to execute c code in the kernel.

(qemu) info mem

vaddr paddr size attr

---------------- ---------------- ---------------- -------

000000000c000000 000000000c000000 0000000000001000 rw---ad

000000000c001000 000000000c001000 0000000000001000 rw-----

000000000c002000 000000000c002000 0000000000001000 rw---ad

000000000c003000 000000000c003000 00000000001fe000 rw-----

000000000c201000 000000000c201000 0000000000001000 rw---ad

000000000c202000 000000000c202000 00000000001fe000 rw-----

0000000010000000 0000000010000000 0000000000002000 rw---ad

0000000080000000 0000000080000000 0000000000007000 r-x--a-

0000000080007000 0000000080007000 0000000000001000 r-x----

0000000080008000 0000000080008000 0000000000012000 rw---ad

000000008001a000 000000008001a000 0000000000001000 rw-----

000000008001b000 000000008001b000 0000000000005000 rw---ad

0000000080020000 0000000080020000 0000000000006000 rw-----

0000000080026000 0000000080026000 0000000000001000 rw---ad

0000000080027000 0000000080027000 0000000007f35000 rw-----

0000000087f5c000 0000000087f5c000 000000000001c000 rw---ad

0000000087f78000 0000000087f78000 0000000000088000 rw-----

0000003ffff7f000 0000000087f78000 000000000003e000 rw-----

0000003fffffb000 0000000087fb6000 0000000000002000 rw---ad

0000003ffffff000 0000000080007000 0000000000001000 r-x--a-Note that we just switched the page table while executing the

code in trampoline page, you may wonder that why isn’t there a crash at

this point. The reason is that both kernel page table

and user page table maps the trampoline page (same va) into same pa.

(bottom of two page tables, both of them maps

0x0000003ffffff000 into

0x0000000080007000)

3. usertrap

After the last jr t0 instruction in trampoline,

we are now in the usertrap c code in the

kernel.

// kernel/trap.c

//

// handle an interrupt, exception, or system call from user space.

// called from trampoline.S

//

void

usertrap(void)

{

int which_dev = 0;

if((r_sstatus() & SSTATUS_SPP) != 0)

panic("usertrap: not from user mode");

// send interrupts and exceptions to kerneltrap(),

// since we're now in the kernel.

w_stvec((uint64)kernelvec);

struct proc *p = myproc();

// save user program counter.

p->trapframe->epc = r_sepc();

if(r_scause() == 8){

// system call

if(p->killed)

exit(-1);

// sepc points to the ecall instruction,

// but we want to return to the next instruction.

p->trapframe->epc += 4;

// an interrupt will change sstatus &c registers,

// so don't enable until done with those registers.

intr_on();

syscall();

} else if((which_dev = devintr()) != 0){

// ok

} else {

printf("usertrap(): unexpected scause %p pid=%d\n", r_scause(), p->pid);

printf(" sepc=%p stval=%p\n", r_sepc(), r_stval());

p->killed = 1;

}

if(p->killed)

exit(-1);

// give up the CPU if this is a timer interrupt.

if(which_dev == 2)

yield();

usertrapret();

}i. Switch to kernel trap handler

// send interrupts and exceptions to kerneltrap(),

// since we're now in the kernel.

w_stvec((uint64)kernelvec);The way xv6 handles traps is different depending on whether they come

from user space or from the kernel. Since we are now in the kernel

space, we change the stvec to point to this

kernelvec which is the kernel trap handler rather than

current user trap handler.

ii. Figure out current running process

struct proc *p = myproc();We need to figure out what process we’re running by calling that

myproc function.

myproc actually use the current cpu id by

read the $tp which we set in trampoline page, to index the

current process id.

iii. Save the user program counter

p->trapframe->epc = r_sepc();As we can see in ecall the saved user

pc is still sitting there in $sepc, but one of the thing

that could happen while we are in the kernel is that we might switch to

another process. And that process might going to that process’user space

and may make a system call which causes $sepc to be

overwritten. We have to save our $sepc in some

memory associate with this process.

iv. Figure out why we came here

if(r_scause() == 8){

// system call

if(p->killed)

exit(-1);

// sepc points to the ecall instruction,

// but we want to return to the next instruction.

p->trapframe->epc += 4;

// an interrupt will change sstatus &c registers,

// so don't enable until done with those registers.

intr_on();

syscall();When ecall being executed, despite the 3 most

important instructions, actually the machine will set

$scause to reflect the trap’s cause. If

$scause is equal to 8, which means we came here because of

a system call, so we’re gonna execute this if statement.

After we set the pc+4, which make sure that after the

whole system call return, we will resume our user code, and enable

interrupts. We are now in the entry of the system call handler ->

syscall.

4. syscall

// kernel/syscall.c

void

syscall(void)

{

int num;

struct proc *p = myproc();

num = p->trapframe->a7;

if(num > 0 && num < NELEM(syscalls) && syscalls[num]) {

p->trapframe->a0 = syscalls[num]();

} else {

printf("%d %s: unknown sys call %d\n",

p->pid, p->name, num);

p->trapframe->a0 = -1;

}

}The syscall function is simple, after get

current process, it just retrieves that $a7 register which

we was saved away in the trap frame by the trampoline code. And then

indexes into that syscalls table, and then calls that function.

And the return value of that syscall function is stored in register

$a0 of that trap frame.

(gdb) stepi

sys_write () at kernel/sysfile.c:83If we use gdb to step into that function, now we are in

sys_write, which is the kernel

implementation of the write system call.

// kernel/sysfile.c

uint64

sys_write(void)

{

struct file *f;

int n;

uint64 p;

if(argfd(0, 0, &f) < 0 || argint(2, &n) < 0 || argaddr(1, &p) < 0)

return -1;

return filewrite(f, p, n);

}Since we are now only interested in getting into and out of the kernel, we are going to step over the actual implementation of system call.

5. usertrapret

// kernel/trap.c

void

usertrapret(void)

{

struct proc *p = myproc();

// we're about to switch the destination of traps from

// kerneltrap() to usertrap(), so turn off interrupts until

// we're back in user space, where usertrap() is correct.

intr_off();

// send syscalls, interrupts, and exceptions to trampoline.S

w_stvec(TRAMPOLINE + (uservec - trampoline));

// set up trapframe values that uservec will need when

// the process next re-enters the kernel.

p->trapframe->kernel_satp = r_satp(); // kernel page table

p->trapframe->kernel_sp = p->kstack + PGSIZE; // process's kernel stack

p->trapframe->kernel_trap = (uint64)usertrap;

p->trapframe->kernel_hartid = r_tp(); // hartid for cpuid()

// set up the registers that trampoline.S's sret will use

// to get to user space.

// set S Previous Privilege mode to User.

unsigned long x = r_sstatus();

x &= ~SSTATUS_SPP; // clear SPP to 0 for user mode

x |= SSTATUS_SPIE; // enable interrupts in user mode

w_sstatus(x);

// set S Exception Program Counter to the saved user pc.

w_sepc(p->trapframe->epc);

// tell trampoline.S the user page table to switch to.

uint64 satp = MAKE_SATP(p->pagetable);

// jump to trampoline.S at the top of memory, which

// switches to the user page table, restores user registers,

// and switches to user mode with sret.

uint64 fn = TRAMPOLINE + (userret - trampoline);

((void (*)(uint64,uint64))fn)(TRAPFRAME, satp);

}i. Change stvec to the user trap handler

// send syscalls, interrupts, and exceptions to trampoline.S

w_stvec(TRAMPOLINE + (uservec - trampoline));The reason we turn off interrupts because once we changed the user trap handler, we’re still executing in the kernel, and if an interrupt occur then it would go to the user trap handler even though we’re executing in the kernel.

ii. Prepare the trap frame for the next kernel re-entering

// set up trapframe values that uservec will need when

// the process next re-enters the kernel.

p->trapframe->kernel_satp = r_satp(); // kernel page table

p->trapframe->kernel_sp = p->kstack + PGSIZE; // process's kernel stack

p->trapframe->kernel_trap = (uint64)usertrap;

p->trapframe->kernel_hartid = r_tp(); // hartid for cpuid()iii.

Ready to execute the userret asm code in trampoline.s

// set S Exception Program Counter to the saved user pc.

w_sepc(p->trapframe->epc);

// tell trampoline.S the user page table to switch to.

uint64 satp = MAKE_SATP(p->pagetable);

// jump to trampoline.S at the top of memory, which

// switches to the user page table, restores user registers,

// and switches to user mode with sret.

uint64 fn = TRAMPOLINE + (userret - trampoline);

((void (*)(uint64,uint64))fn)(TRAPFRAME, satp);- Write the resume user-code pc which located in

$epcto the$satpso that thesretinstruction can assign that value into pc when switching to the user space. - Cook up the

$satp, which will be used in the trampoline code later. - Get the location of

userretin trampoline.s, and then call that function with theTRAPFRAMEandsatparguments passing.

6. userret

.globl userret

userret:

# userret(TRAPFRAME, pagetable)

# switch from kernel to user.

# usertrapret() calls here.

# a0: TRAPFRAME, in user page table.

# a1: user page table, for satp.

# switch to the user page table.

csrw satp, a1

sfence.vma zero, zero

# put the saved user a0 in sscratch, so we

# can swap it with our a0 (TRAPFRAME) in the last step.

ld t0, 112(a0)

csrw sscratch, t0

# restore all but a0 from TRAPFRAME

ld ra, 40(a0)

ld sp, 48(a0)

ld gp, 56(a0)

ld tp, 64(a0)

ld t0, 72(a0)

ld t1, 80(a0)

ld t2, 88(a0)

ld s0, 96(a0)

ld s1, 104(a0)

ld a1, 120(a0)

ld a2, 128(a0)

ld a3, 136(a0)

ld a4, 144(a0)

ld a5, 152(a0)

ld a6, 160(a0)

ld a7, 168(a0)

ld s2, 176(a0)

ld s3, 184(a0)

ld s4, 192(a0)

ld s5, 200(a0)

ld s6, 208(a0)

ld s7, 216(a0)

ld s8, 224(a0)

ld s9, 232(a0)

ld s10, 240(a0)

ld s11, 248(a0)

ld t3, 256(a0)

ld t4, 264(a0)

ld t5, 272(a0)

ld t6, 280(a0)

# restore user a0, and save TRAPFRAME in sscratch

csrrw a0, sscratch, a0

# return to user mode and user pc.

# usertrapret() set up sstatus and sepc.

sretAfter the first instruction, as we can see, now we are in the much smaller user page table but luckily still with the trampoline page map so we don’t crash on the next instruction.

(qemu) info mem

vaddr paddr size attr

---------------- ---------------- ---------------- -------

0000000000000000 0000000087f61000 0000000000001000 rwxu-a-

0000000000001000 0000000087f5e000 0000000000001000 rwxu-a-

0000000000002000 0000000087f5d000 0000000000001000 rwx----

0000000000003000 0000000087f5c000 0000000000001000 rwxu-ad

0000003fffffe000 0000000087f70000 0000000000001000 rw---ad

0000003ffffff000 0000000080007000 0000000000001000 r-x--a-Back to 4.syscall, when we are executing the

syscall, we store the return value into

p->trapframe->a0. Since the current value of

$a0 is the TRAPFRAME address, we cannot

overwrite it, until we restore all saved registers. So we load the

p->trapframe->a0 into $t0, and then swap

it with $sscratch.

(gdb) print/x $a0

$9 = 0x3fffffe000

(gdb) print/x $sscratch

$10 = 0x1After that, we restore all registers but $a0

from TRAPFRAME, finally, we swap $sscratch and

$a0 both restore the correct return value of

syscall and load the TRAPFRAME into

$sscratch, so that the trap handling code that we talked

about before will be able to use that $sscratch to get at

the trap frame.

(gdb) print/x $sscratch

$11 = 0x3fffffe000ra 0xe82 0xe82

sp 0x3e90 0x3e90

gp 0x505050505050505 0x505050505050505

tp 0x505050505050505 0x505050505050505

t0 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

t1 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

t2 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

fp 0x3eb0 0x3eb0

s1 0x12e1 4833

a0 0x1 1

a1 0x3e9f 16031

a2 0x1 1

a3 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

a4 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

a5 0x2 2

a6 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

a7 0x10 16

s2 0x24 36

s3 0x0 0

s4 0x25 37

s5 0x2 2

s6 0x3f50 16208

s7 0x1480 5248

s8 0x15 21

s9 0x1428 5160

s10 0x10 16

s11 0x28 40

t3 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

t4 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

t5 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

t6 0x505050505050505 361700864190383365

pc 0x3ffffff10e 0x3ffffff10eNow all these 32 general-purpose registers happen to be the same set of registers before we make that system call in user space. We are now ready to jump back to user code and resume the procedure after system call.

7. sret

Same as ecall, the sret instruction

does many things for us. 1. Switch to user

mode. 2. Copy $sepc to

$pc.

(gdb) stepi

0x0000000000000dee in ?? ()

=> 0x0000000000000dee: 82 80 ret

(gdb) print/x $pc

$12 = 0xdeeNow we are back to the shell, just at the very next instruction of

ecall. And that is the whole procedure of

a Trap.

8. Summary

To wrap up, the system calls are sort of look like function calls but the user-kernel transitions are much more complex than normal function calls are.

A lot of the complexities due to the requirement for isolation, because the kernel just can’t trust anything in user space, that makes many instructions cannot be executed in user space.