2. Virtual Memory

03/03/2022 By Angold Wang

Kernel with “Isolation”

- Restrict each user processes so that all it can do is read/write/execute its own user memory, and use the 32 gerneral-purpose RISC-V registers.

- One user-process can only affect the kernel and other processes in the ways that system calls are intended to allow

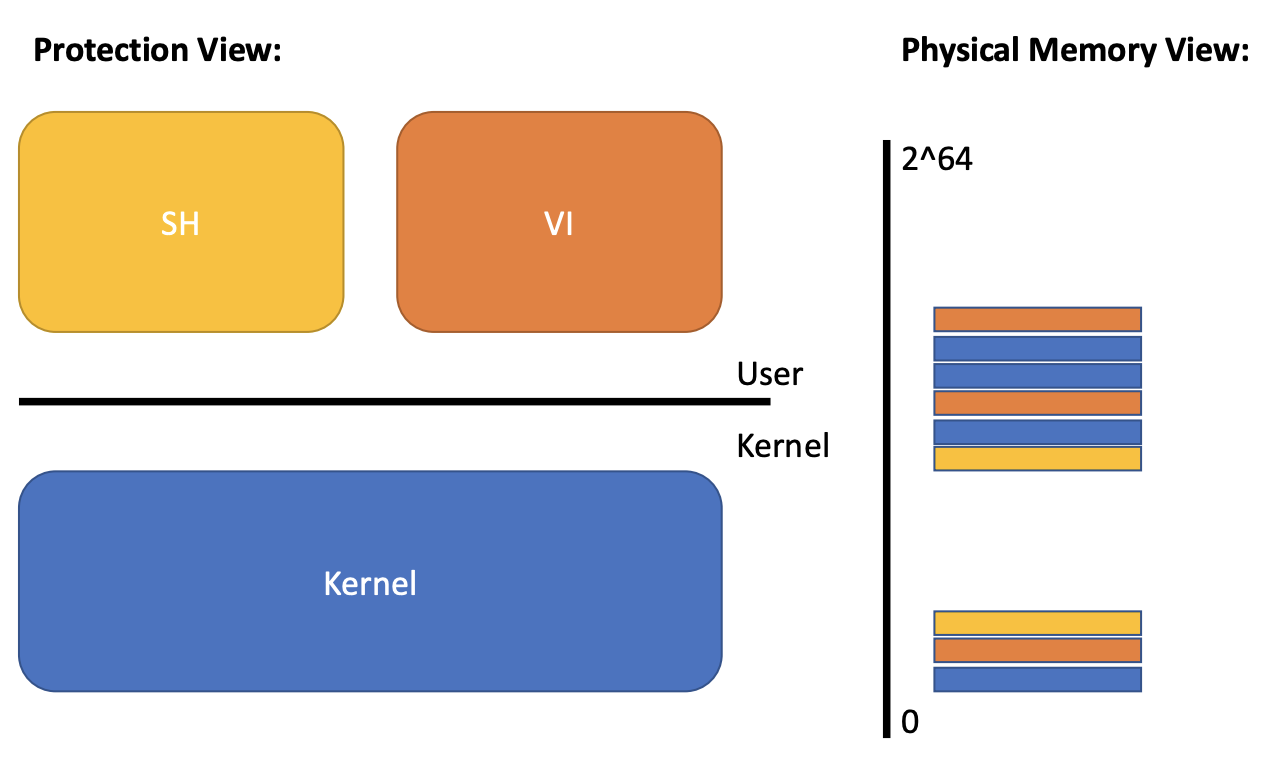

1. Memory Isolation

The RISC-V instructions (both user and kernel) manipulate virtual addresses. But machine’s RAM, or physical memory, is indexed with physical addresses.

In the last note, we mentioned that one way to bring isolation is through Virtual Memory. The main purpose of Virtual Memory is to achieve strong Memory Isolation.

- Each process has its own memory

- It can read and write its own memory

- It cannot read or write anything else directly (must through syscall, with privileges)

- Each process believes that they have full memory space under control (Two processes with “same” virtual address)

How to multiplex several memories over one physical memory? while maintaining isolation between memories.

2. Paging Hardware

i. Level of Indirection Indexing

- Software can only read and write to virtual memory.

- Only kernel can program mmu (Memory Manage Unit), which means this VA -> PA mapping is completely under the control of the Operating System.

- MMU has a Page table that maps virtual addresses to physical adresses.

- Some virtual addresses restricted to kernel-only.

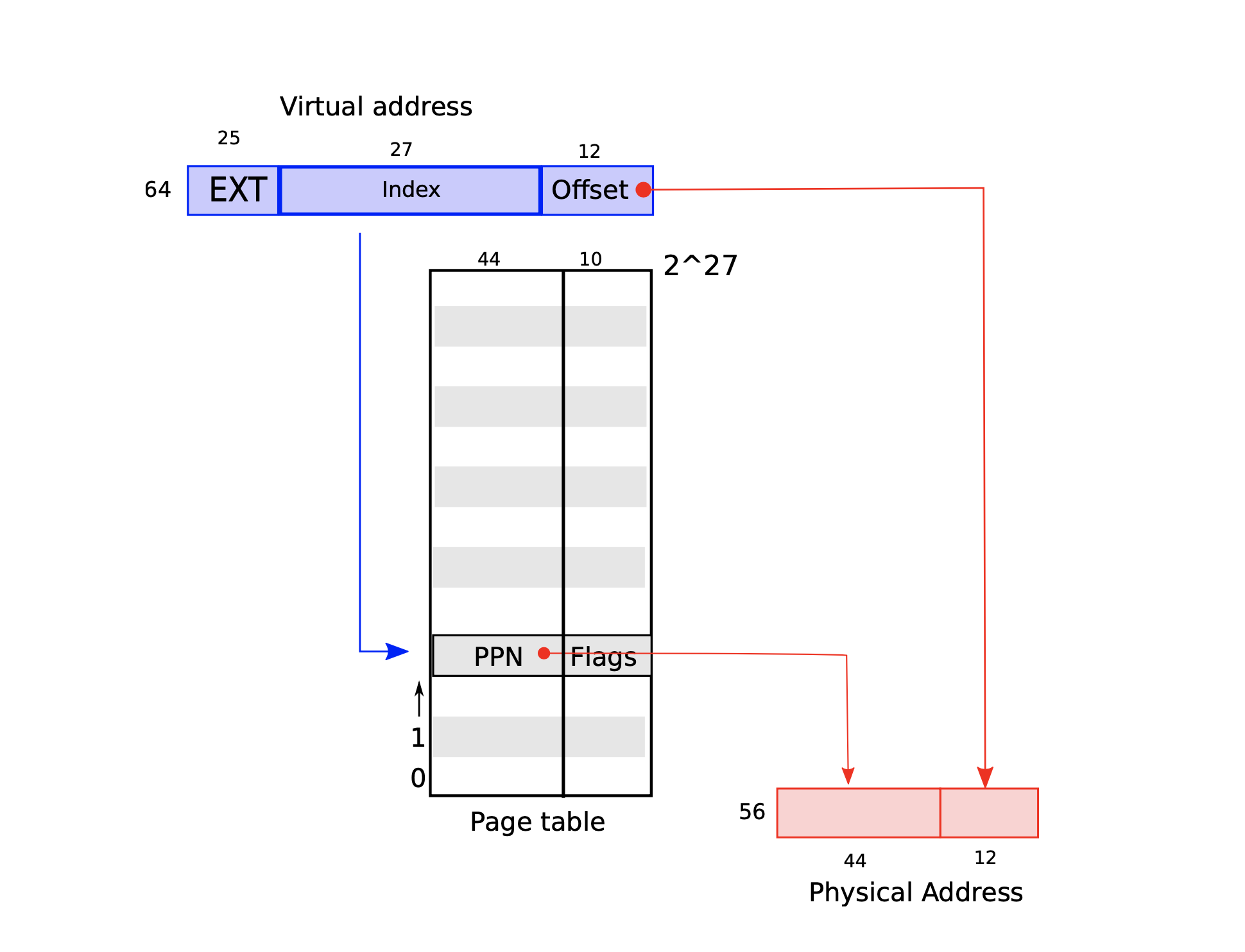

ii. Virtual Address to Page

Why we need page?

Imagine that a 64-bit machine, which means it support

2^64 memory address, if we just simply map one

VA into one PA, the mapping table

continuous store in memory will be also 2^64 – which is

gigantic.

So we use another way, instead store this mapping

relationship in a very gigantic continuous mapping array, we divide them

into different pages, and each virtual address contains two message:

page_id and offset.

Each process has its own page_table, which

managed by the kernel, here is the

proc structure in xv6:

struct proc {

struct spinlock lock;

// p->lock must be held when using these:

enum procstate state; // Process state

void *chan; // If non-zero, sleeping on chan

int killed; // If non-zero, have been killed

int xstate; // Exit status to be returned to parent's wait

int pid; // Process ID

// wait_lock must be held when using this:

struct proc *parent; // Parent process

// these are private to the process, so p->lock need not be held.

uint64 kstack; // Virtual address of kernel stack

uint64 sz; // Size of process memory (bytes)

pagetable_t pagetable; // User page table (Which table / start address)

struct trapframe *trapframe; // data page for trampoline.S

struct context context; // swtch() here to run process

struct file *ofile[NOFILE]; // Open files

struct inode *cwd; // Current directory

char name[16]; // Process name (debugging)

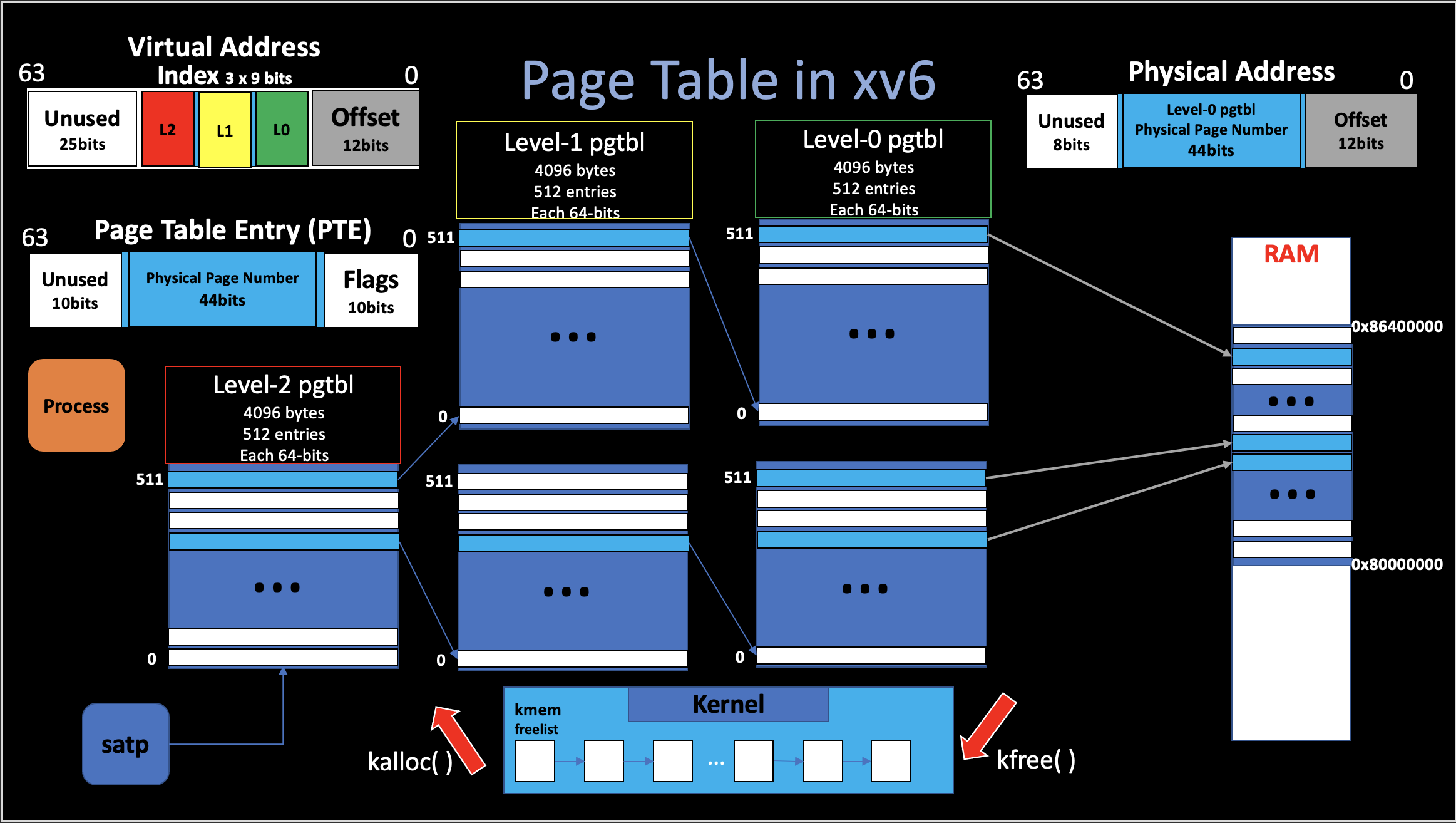

};High-level view of xv6 page table

xv6 runs on Sv39 RISC-V, which means that only the bottom

39 bits of a 64-bit virtual address. A RISC-V page

table is logically an array of 2^27

(134,217,728) page table entries (PTE). Each PTE contains a

44-bit physical page number (PPN) and 10-bit

flags.

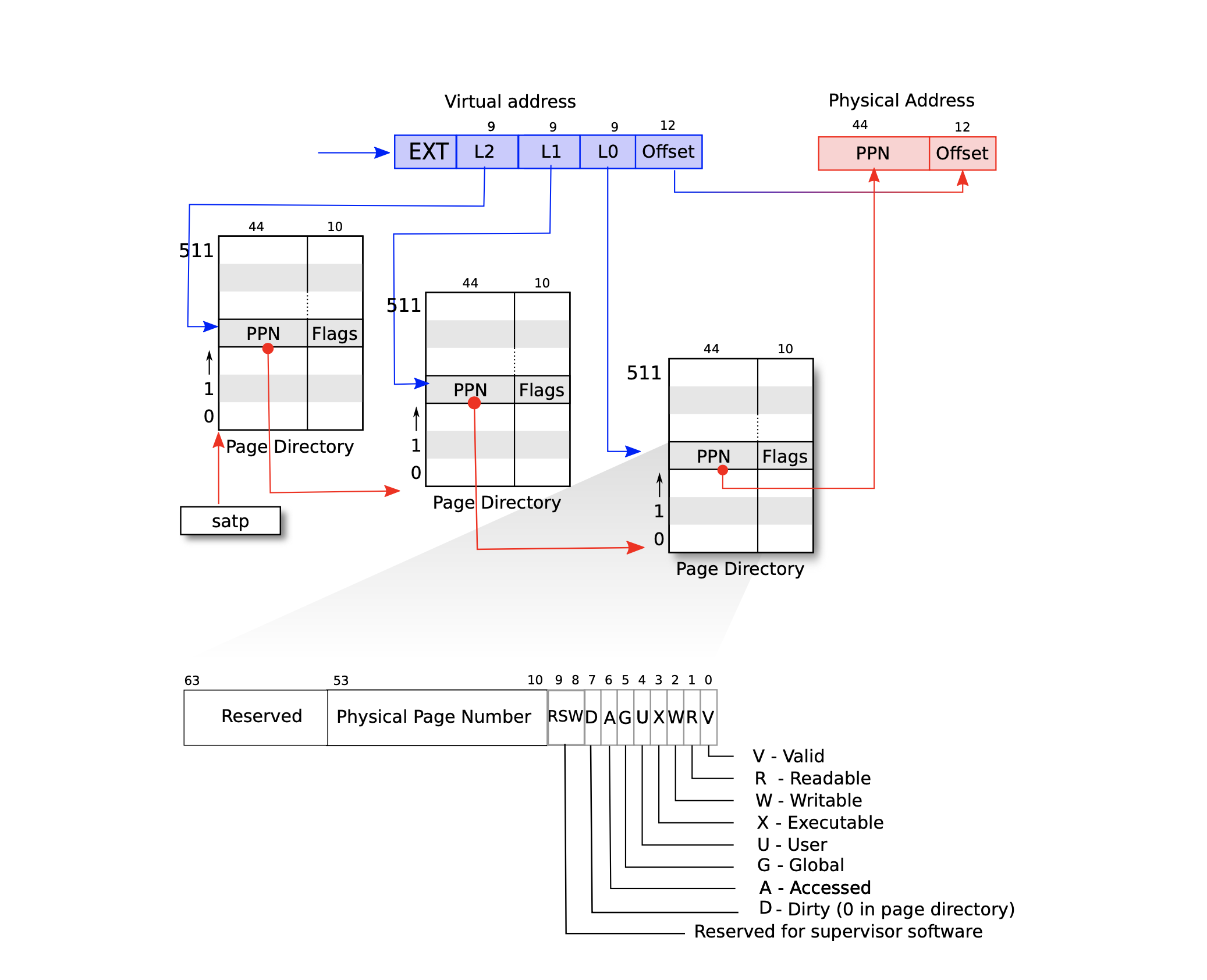

iii. Page to Page Directory

Revisted: Would it be reasonable for page table to just be an

array of PTEs? * 2^27 is roughly

134 millions * 64 bits per

page entry * 134 * 8bytes * million for a

full page table * wasting roughly 1GB per page

table * one page table per address space * one address space per

application * Would waste losts of memory for small

programs! * you only need mappings for a few hundred pages. *

so the rest of the million entries would be there but not needed

Satp Register

Each CPU core has its own unique %satp

register, where store the current-running process’s page table starting

address of its CPU. That makes different CPUs can run different

processes, each with a private address space described by its

own page table.

3-level page table (Page Directory)

As we see that above, it is not good to just simply have a giant page

table per process. In real translation at MMU, A page table is

stored in physical memory as a three-level tree. Each level is a page

directory, which is 4096 bytes, and contains

512 (2^9) 64-bit page table entries. And that 3-level

2^9 PTEs can be located via the first 27 bits virtual

address.

This three-level structure of above figure allows a memory-efficient way of recording PTEs, which means in the 3-level page table, you can leave a lot of entries empty.

For example, if you leave the entry in the top level page table directory empty, for those entries, you don’t have to create middle level page tables or bottom level page tables at all. And then we can allowcate these chunks on demand.

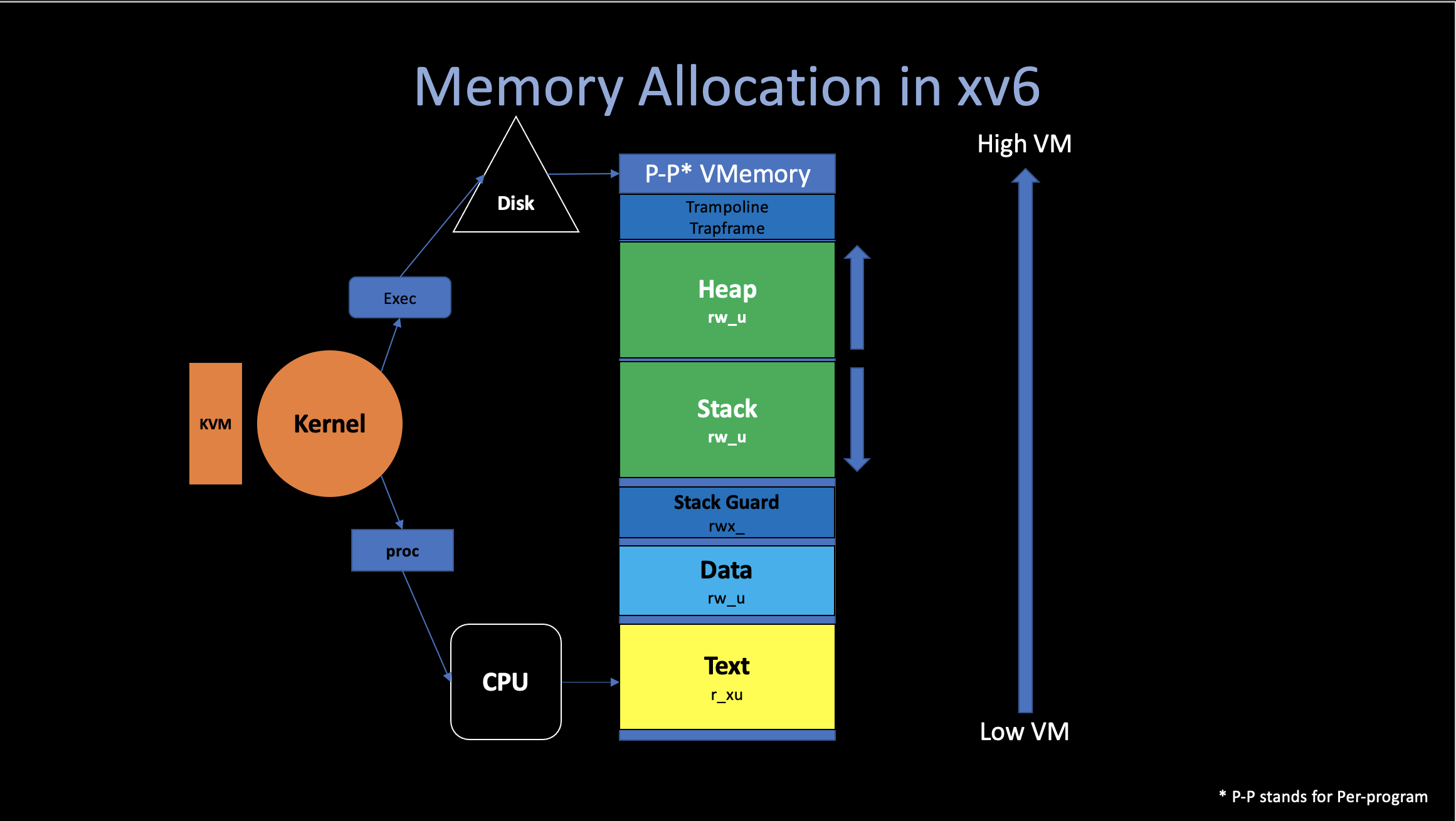

3. Page Table Implementation in xv6

The kernel must allocate and free physical memory at run-time

for page tables, and it uses a very small allocator resides

in kalloc.c (kernel/kalloc.c) to do these

stuff.

i. Initialize

For simplicity, the allocator can only use physical memory between

KERNBASE (0x80000000L) and

PHYSTOP(0x86400000L) to allocate pages,

which is about 104MB. The xv6 assumes that the machine has 128 megabytes

of RAM.

The main calls

kinit to initialze the allocator.

kinit initialzes the free list

(freelist) to hold every pages in the

physical memory (104MB).

A PTE can only refer to a physical address that is aligned on a 4096-byte boundary (is a multiple of 4096).

If some process need to shrink or grow its memory, it will call

syscall sbrk(). And this syscall will call

whether uvmalloc() or

uvmdealloc() in order to perform the task.

* To shrink the memory. The task is done by

kfree(), which append the unused memory

pages into the free list page by page. * To grow the

memory. The task is done by

kalloc(), which “pop” the number of pages

from the free list.

ii. Code: walk()

If you want to study the actual implementation of xv6 Virtual Memory,

I highly recommend you to read these two functions:

walk() and

mappages().

Since the allocator sometimes treats address as integers in

order to perform arithmetic on them (e.g., traversing all pages

by adding PGSIZE), and sometimes uses addresses as

pointers to read and write memory (e.g., manipulating

the run structure stored in each page), which makes the

code a little bit sophisticated.

// Return the address of the PTE in page table pagetable

// that corresponds to virtual address va. If alloc!=0,

// create any required page-table pages.

//

// The risc-v Sv39 scheme has three levels of page-table

// pages. A page-table page contains 512 64-bit PTEs.

// A 64-bit virtual address is split into five fields:

// 39..63 -- must be zero.

// 30..38 -- 9 bits of level-2 index.

// 21..29 -- 9 bits of level-1 index.

// 12..20 -- 9 bits of level-0 index.

// 0..11 -- 12 bits of byte offset within the page.

pte_t *

walk(pagetable_t pagetable, uint64 va, int alloc)

{

if(va >= MAXVA)

panic("walk");

for(int level = 2; level > 0; level--) {

// pagetable -> pointer

pte_t *pte = &pagetable[PX(level, va)]; // 4096 bytes / 2^9 = 64 bits (a pte)

if(*pte & PTE_V) {

pagetable = (pagetable_t)PTE2PA(*pte); // next pgtbl's begin address

} else {

if(!alloc || (pagetable = (pde_t*)kalloc()) == 0)

return 0;

memset(pagetable, 0, PGSIZE);

*pte = PA2PTE(pagetable) | PTE_V;

}

}

return &pagetable[PX(0, va)]; // only need 9 bits to get a valid pte (64bits)

}The walk() functions basically performs

so-called Software Translate, which return the

Level-0 pte of given virtual address in that page

table.

This work usually is done by the MMU Hardware, with

the help of satp register. And is much faster than this

function. But sometimes the page table we need is not in the

%satp register. (e.g., the kernel wants to dereference the

user virtual address pointers that write()

system call passed).

// Create PTEs for virtual addresses starting at va that refer to

// physical addresses starting at pa. va and size might not

// be page-aligned. Returns 0 on success, -1 if walk() couldn't

// allocate a needed page-table page.

int

mappages(pagetable_t pagetable, uint64 va, uint64 size, uint64 pa, int perm)

{

uint64 a, last;

pte_t *pte;

if(size == 0)

panic("mappages: size");

a = PGROUNDDOWN(va); // 0000 in the last (begin a page)

last = PGROUNDDOWN(va + size - 1);

for(;;){

if((pte = walk(pagetable, a, 1)) == 0) // software walk get the last(0) level pte

return -1;

if(*pte & PTE_V) // last pte value

panic("mappages: remap");

// the pte is a pointer, points to the real physical address

*pte = PA2PTE(pa) | perm | PTE_V; // PTE

if(a == last)

break;

a += PGSIZE;

pa += PGSIZE;

}

return 0;

}The mappages() creating mappings

between virtual and physical addresses. The pagetable_t is

a pointer, which points to the begin of a 4096 bytes

page.