The Rust Programming Language

Angold Wang | 2022-03-24

1. Why Rust?

“Safe System Performance Programming”

- System Programming Language: C, C++.

- Safe Programming Language: ML, Haskell, Java

Mozilla trying to blend the best of both of these languages.

Why is Mozilla interested in creating a new programming language?

- Mozilla is the organization that created the Firefox web browser, current written in C++.

- Web browsers need a high degree of control over the

machine.

- Doing very complex tasks very quickly (all these tabs running simultaneously)

- Web browsers need safety

- Running untrusted code, which is been downloaded from internet.

- Languages like C/C++ that give you the kind of control you need in order to get the performance, but also leave you open to all kinds of security vulnerabilities.

- Mozilla want to build the next generation web browser, which is a project called servo. And they wants to do it in a new language that tries to do better at giving you both control and safety at the same time.

2. Control - Case study: Zero-Cost Abstraction in C / C++

C and C++ is sort of the best existing language in this respect (control).

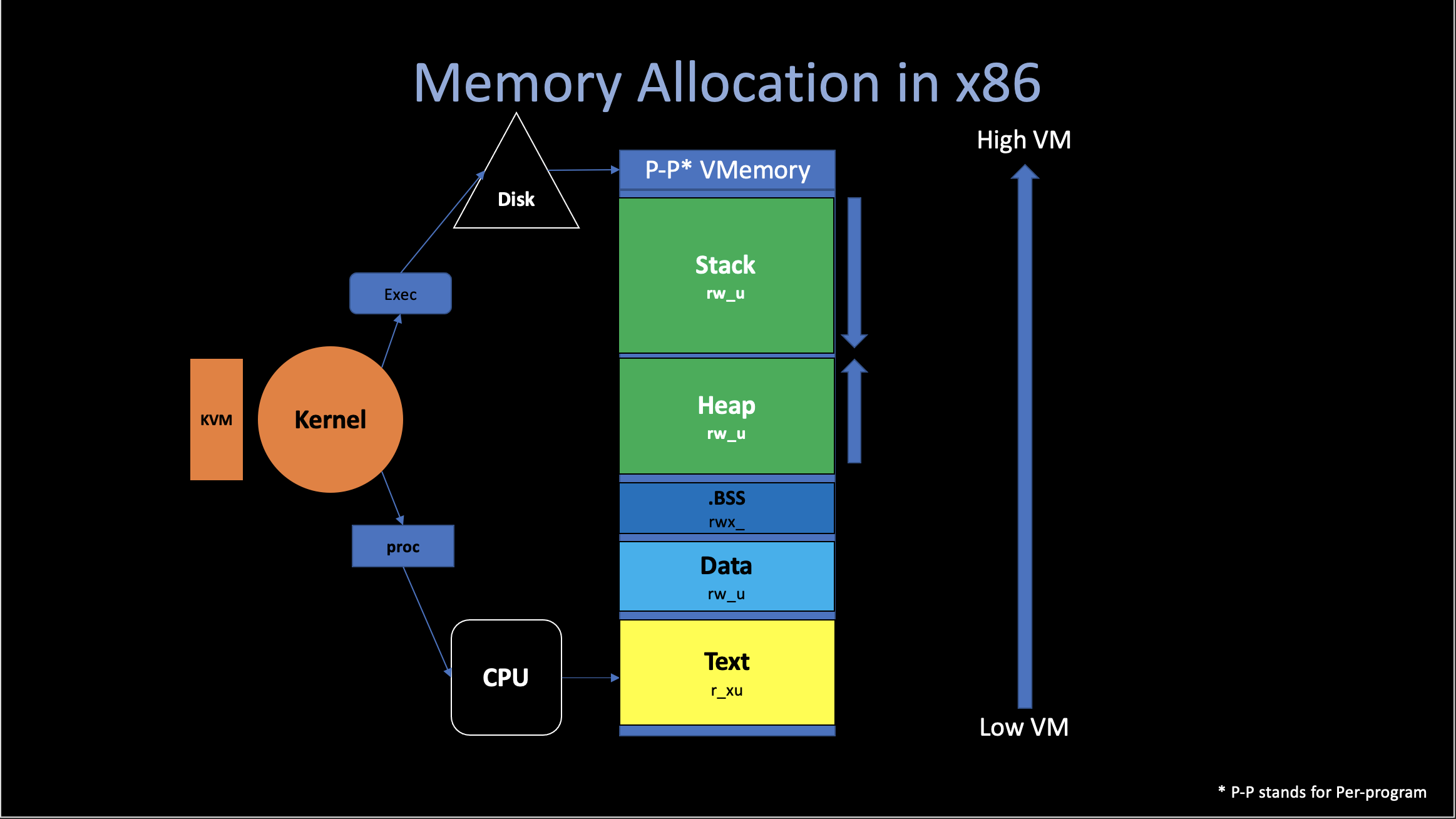

i. Memory Allocation

Basically, there are four places in Memory for C/C++ program to store data.

1. Stack

Most of the temporary variables created at runtime are stored in the stack. They are created (push) when the corresponding procedure is called and destroyed (pop) when returns.

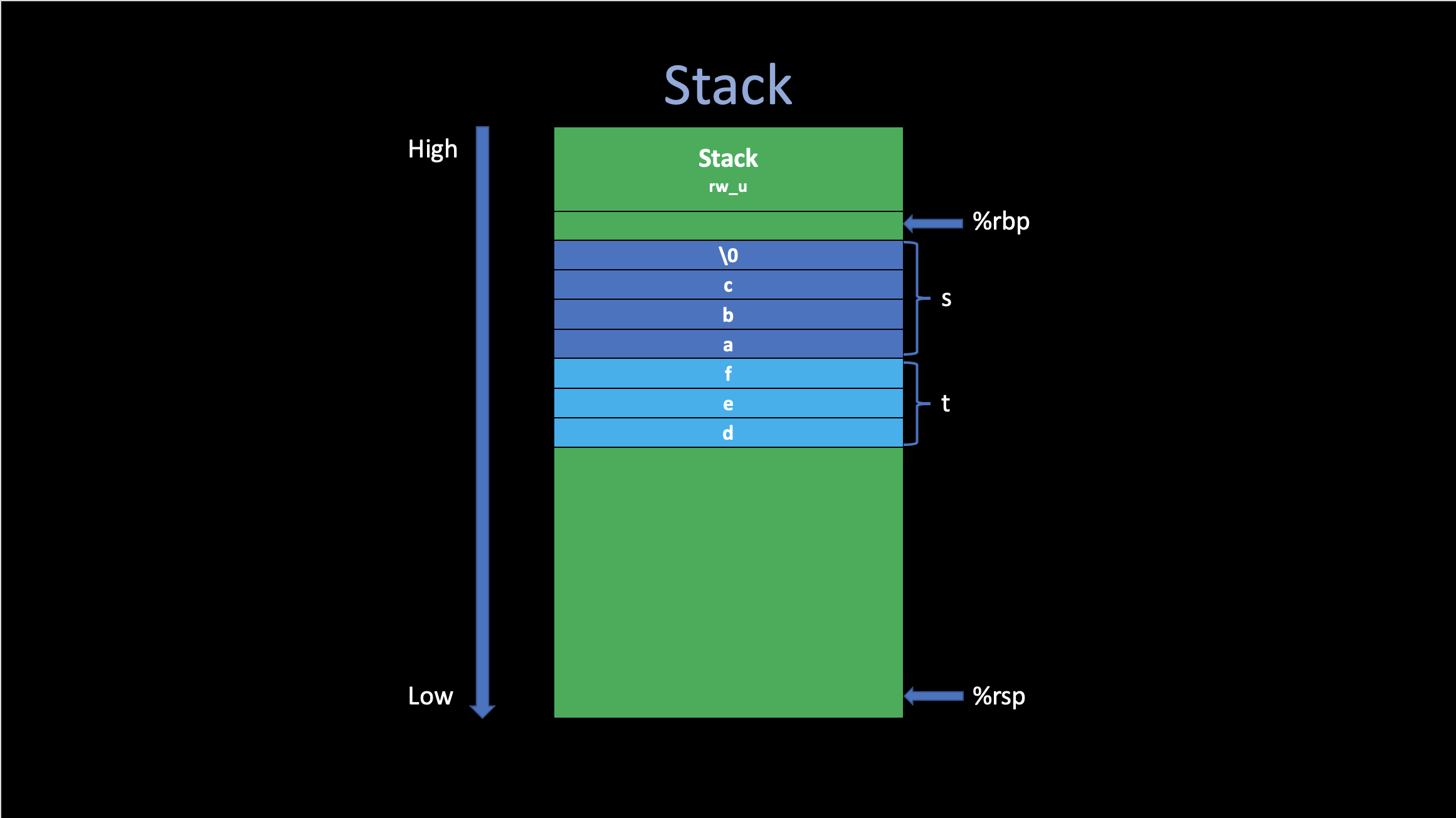

Consider the following C code snippet:

char s[] = "abc"; // {'a', 'b', 'c', 'd', '\n'}

char t[3] = "def";

printf("s: %s\n", s);

printf("t: %s\n", t);The output of this process looks strange:

s: abc

t: defabcAfter check the generated assembly code in char.s, It is easy to figure out why

t becomes

defabc.

Since printf only stops looking for the next

byte when encounters \0 (terminator). If we do not

define the variable with the correct format and size, because these temp

data are stored in the stack, sometimes it will cause some unexpected

errors.

2. Text

The Text segment has e bit enabled, the compiler

generate program instructions in this segment. And this segment also

hardcodes all “strings” that was defined inside the

function.

.section __TEXT,__cstring,cstring_literals

L___const.main.s: ## @__const.main.s

.asciz "abc"

.section __TEXT,__const

l___const.main.t: ## @__const.main.t

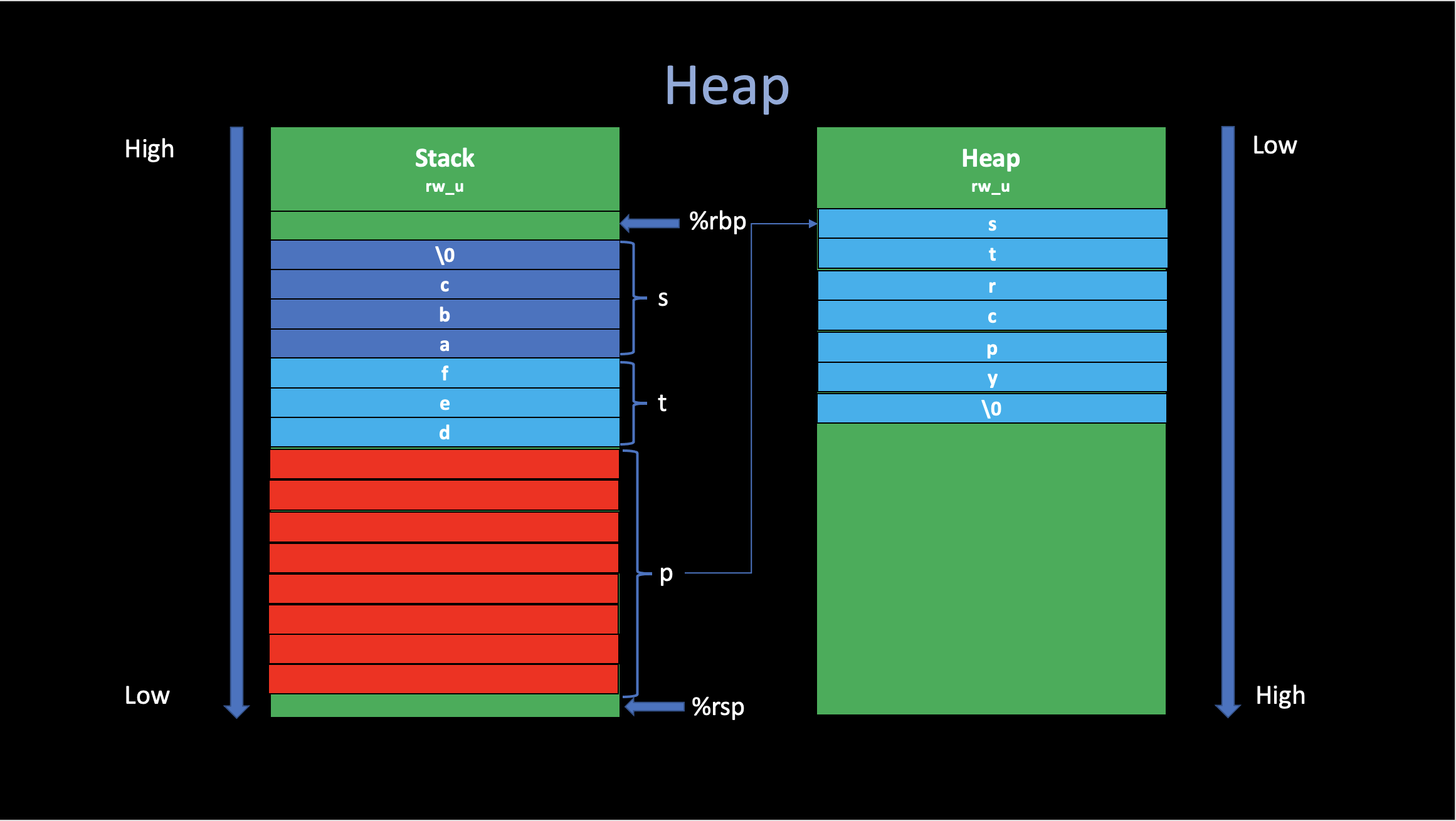

.ascii "def"3. Heap

In C, the malloc() function will allocate a

memory in Heap, and then return the begin address of that chunk of new

memory.

char *p = malloc(6*sizeof(char));

strcpy(p, "strcpy");

printf("p: %s\n", p); // strcpy

4. Data

The Data segment contains global data. Which can be accessed from all functions in the current program.

.section __DATA,__data

.globl _data ## @data

.p2align 2

_data:

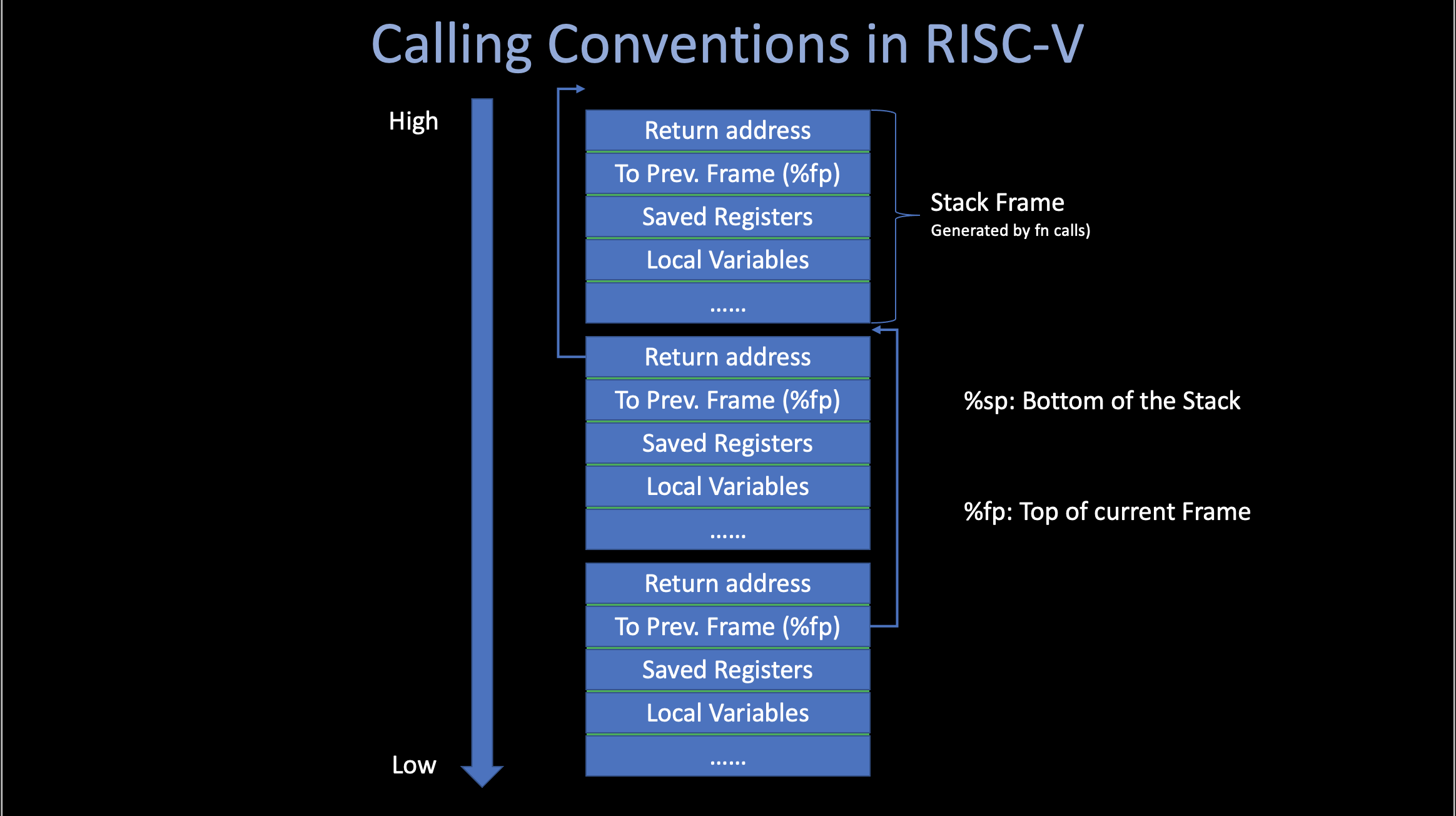

.long 12345 ## 0x3039ii. Calling Conventions

The calling conventions describes the interface of the called code. Which makes the caller code can find what they wants (arguments, return address, fp ,etc.)

There are two kinds of the registers in Calling Conventions: caller and callee saved.

Caller-Saved Registers

Not preserved across the call. These are scratch registers - the callee is allowed to scribble over them. So if the caller cares about their contents, the caller must save them into stack before make the call.

Callee-Saved Registers

Preserved across the call. If the callee uses them, then the callee must restore the original values before returning.

Usage of %fp / %rbp

Except for addressing variables in stack, the frame pointer (also called base pointer) are also used in Back Trace. Which can print the calling stack during the fn calling conventions

void

backtrace(void) {

uint64 cur_fp = r_fp();

while (cur_fp != PGROUNDDOWN(cur_fp)) { // Page top

printf("%p\n", *(uint64 *)(cur_fp - 8)); // the return address

cur_fp = *(uint64 *)(cur_fp - 16); // next frame begin

}

}iii. Zero-Cost Abstraction

When we say “Control” in programming language, it usually means “How much control we can get over the machine?”

For example, like what I mentioned earlier. If you declare a

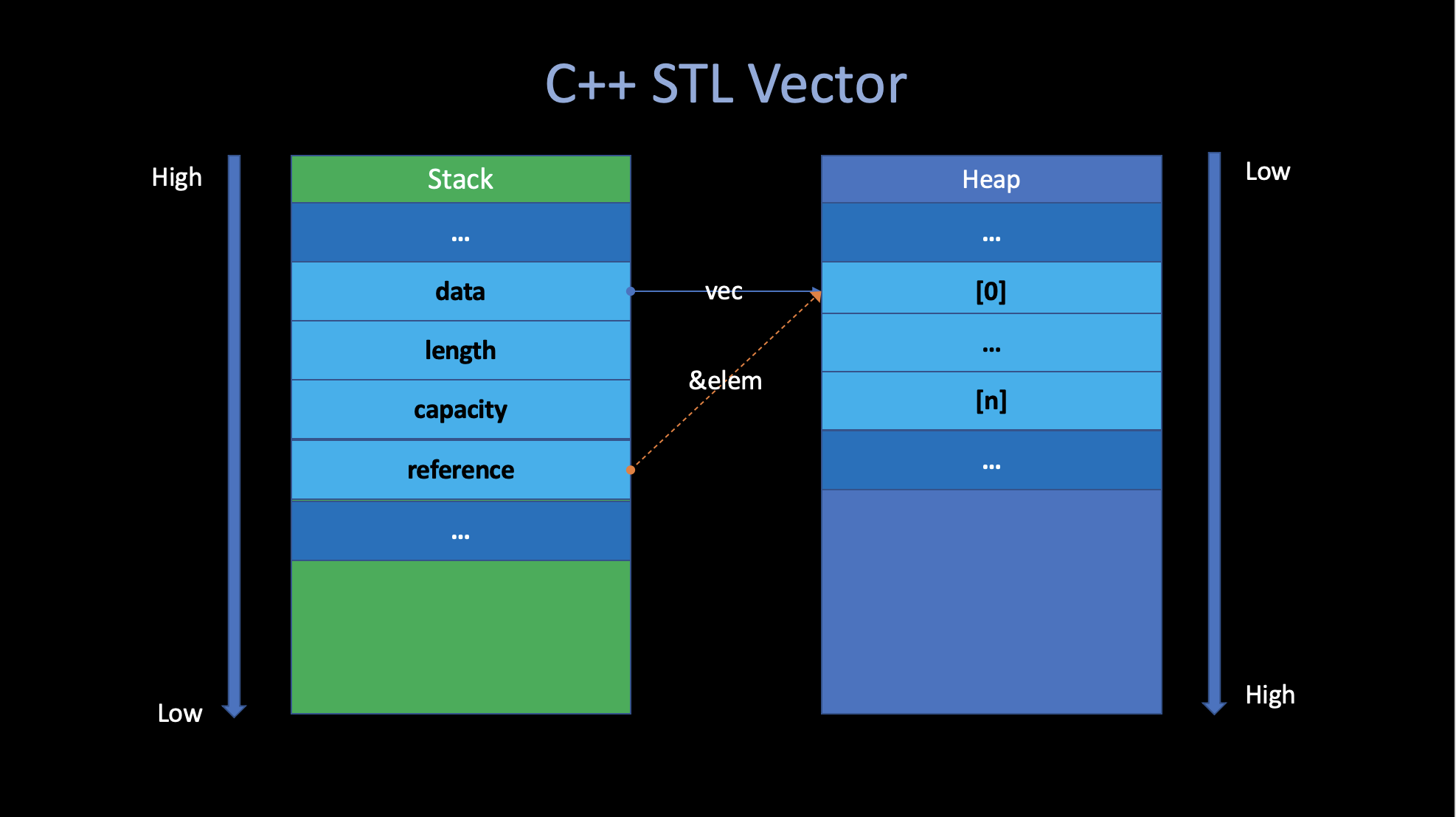

vector in C++ and you’ve read the STL code.

You’ll know exactly how that is going to be laid out in terms of the

memory.

vector<int> vec;

auto& elem = vec[0];In particular, in this code snipper. There are some field of the vector, including a pointer to the actuall data in the heap and some metadata about it, that all live on the stack. And you can have a lot of controls over the layout if you want.

One of the principles that you get out of C++ is something often

called “Zero-cost abstraction”. Which means you can

build libraries like vector or string that are

reasonably convinence to use (they give you nice abstraction).

But if you compile it down. It is nothing different than you

could have written by hand in assembly.

You’re not giving up any performance in doing this abstraction

3. Design Patten

Here I’ll show some design choices/pattens in Rust: Based on the book 《The Rust Programming Language》

0. Compiler Errors

In Rust, compiler errors can be frustrating and occur frequently, but really they only mean your program isn’t safely doing what you want it to do yet; they do not mean that you’re not a good programmer! Experienced Rustaceans still get compiler errors.

Even though these compile errors may be frustrating at times, remember that it’s the Rust compiler pointing out a potential bug early (at compile time rather than at runtime).

1. Mutability

By default variables are immutable. It’s important that we get compile-time errors when we attempt to change a value that’s designated as immutable because this very situation can lead to bugs.

If one part of our code operates on the assumption that a value will never change and another part of our code changes that value, it’s possible that the first part of the code won’t do what it was designed to do. The cause of this kind of bug can be difficult to track down after the fact, especially when the second piece of code changes the value only sometimes.

Shadowing

fn main() {

let x = 5;

let x = x + 1;

{

let x = x * 2;

println!("The value of x in the inner scope is: {x}");

}

println!("The value of x is: {x}");

}The first variable x is shadowed by the

second, means that the second variable is what the compiler will see

when you use the name of the variable in the inner scope. As a

concequence: 1. We do not need to make a new temporary variable name

(e.g., y) to use, we can reuse the same name efficiently. 2. By using

let, we can perform a few operations on a value but have

the variable immutable after those ops have been completed.

$ cargo run

Compiling variables v0.1.0 (file:///projects/variables)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.31s

Running `target/debug/variables`

The value of x in the inner scope is: 12

The value of x is: 62. Statements and Expressions

- Statements are instructions that perform some action and do not return a value.

- Expressions evaluate to a resulting value.

Expressions evaluate to a value and make up most of the rest of the code that you’ll write in Rust.

fn main() {

let y = {

let x = 3;

x + 1

};

println!("The value of y is: {y}");

}The block is an expression, in this case, evaluates to

4. That value gets bound to y as part of the

let statement. Note that the x + 1 line doesn’t have a

semicolon at the end, unlike most of the lines you’ve seen so far.

Expressions do not include ending semicolons. If you

add a semicolon to the end of an expression, you turn it into a

statement, and it will then not return a value.

In Rust, the return value of the function is synonymous with the value of the final expression in the block of the body of a function.

3. Ownership

Ownership is a set of rules that governs how a Rust program manages memory. All programs have to manage the way they use a computer’s memory while running.

In general, there are three ways for programming language to free the unused memory:

- Explicitly allocate and free the memory. (e.g,. C, C++)

- Using Garbage Collector that regularly looks for no-longer used memory as the program runs (e.g,. Java, Go)

- Memory is managed through a system of ownership with a set of rules that the compiler checks. If all rules were followed, the code will be compiled successfully, and the compiler will help you do the deallocation automatically (e.g,. Rust)

Genearally, In the first approach, it’s our responsibility to identify when memory is no longer being used and call code to explicitly free it, just as we did to request it. Doing this correctly has historically been a difficult programming problem. If we forget, we’ll waste memory. If we do it too early, we’ll have an invalid variable. If we do it twice, that’s a bug too. We need to pair exactly one allocate with exactly one free.

In the second approach, we do not need to think about the memory stuff, just keep creating the variables in the heap, and the Garbage Collector (GC) will help us to cleans up the memory that isn’t being used anymore. The GC usually runs aside our program, and will slow it down due to the limited computer resources.

In Rust, the third approach, if we obey the rules of ownership and make the program compiled, none of the features of ownership will slow down your program while it’s running, and you won’t gain any both potential bugs and unreleased unused memory.

The Ownership Rules

- Each value in Rust has an owner.

- There can only be one owner at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope, the value will be dropped automatically

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1; // s2 now own the value of s1

println!("{}, world!", s1); // compile error

// the value is being "moved" from s1 to s2

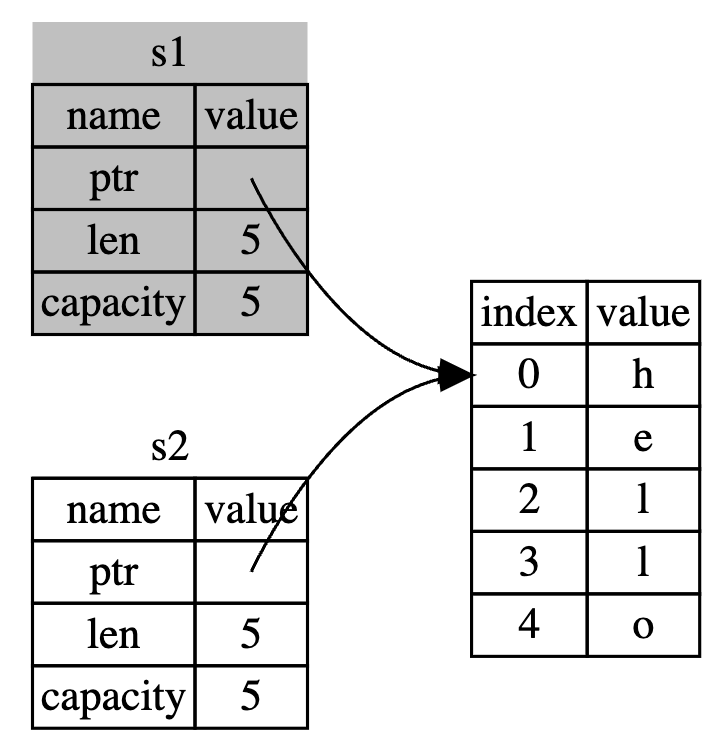

// the s1 has been invalidatedIf you’ve heard the terms shallow copy and deep

copy while working with other languages, the concept of copying the

pointer, length, and capacity without copying the data probably sounds

like making a shallow copy. But because Rust also invalidates

the first variable, instead of calling it a shallow copy, it’s known as

a move. In this example, we would say that

s1 was moved into

s2. So what actually happens is shown in

the following Figure.

Why do we need Ownership?

One of the purpose of the ownership rule is to solve some problems that we usually encounter in Type #1 language like C and C++: The Double Free Error

When a variable goes out of scope, Rust automatically calls the drop function and cleans up the heap memory for that variable. But if both data pointers pointing to the same location. This is a problem: when s2 and s1 go out of scope, they will both try to free the same memory. This is known as a double free error and is one of the memory safety bugs we mentioned previously. Freeing memory twice can lead to memory corruption, which can potentially lead to security vulnerabilities.

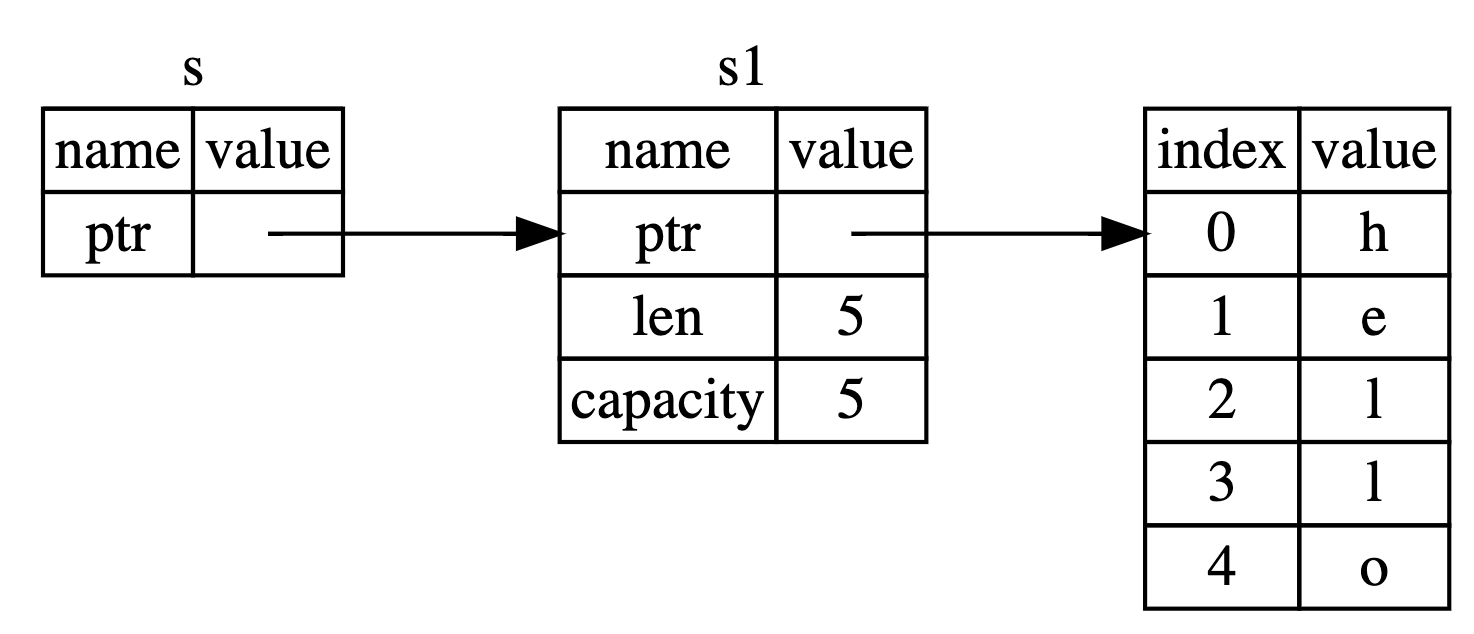

4. Borrowing

Sometimes, after calling a function and give the ownership of that variable to it, we may stll want to use that variable after the function return. (that variable should not be invalidated). The solution is that we can provide a reference to that variable, when we pass that reference, there is no ownership transfer, which means that the function just “borrow” the value of that variable (do not own it).

A reference is like a pointer in that it’s an address we can follow to access the data stored at that address; that data is owned by some other variable. Unlike a pointer, a reference is guaranteed to point to a valid value of a particular type for the life of that reference. (the memory should not be dropped.)

Here is how you would define and use a calculate_length

function that has a reference to an object as a parameter instead of

taking ownership of the value:

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1);

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

} // Here, s goes out of scope. But because it does not have ownership of what

// it refers to, it is not dropped.

Mutable References

Just as variables are immutable by default, so are references. We’re

not allowed to modify something we have a reference to. But you can also

create a mutable reference by adding a mut keyword:

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

change(&mut s);

}

fn change(some_string: &mut String) {

some_string.push_str(", world");

}Mutable references have one big restriction: if you have a mutable reference to a value, you can have no other references to that value. This code that attempts to create two mutable references to s will fail.

The benefit of having this restriction is that Rust can prevent data races at compile time. A data race is similar to a race condition and happens when these three behaviors occur:

- Two or more pointers access the same data at the same time.

- At least one of the pointers is being used to write to the data.

- There’s no mechanism being used to synchronize access to the data.

Data races cause undefined behavior and can be difficult to diagnose and fix when you’re trying to track them down at runtime; Rust prevents this problem by refusing to compile code with data races!

Another restriction of mutable reference is that We also cannot have a mutable reference while we have an immutable one to the same value.

The reason is also relatively simple: Users of an immutable reference don’t expect the value to suddenly change out from under them!

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s; // no problem

let r2 = &s; // no problem

println!("{} and {}", r1, r2);

// variables r1 and r2 will not be used after this point

let r3 = &mut s; // no problem

println!("{}", r3);The scopes of the immutable references r1 and

r2 end after the println! where they are last

used, which is before the mutable reference r3 is created.

These scopes don’t overlap, so this code is allowed.