Operating Systems Design and Implementation Notes

2. Interprocess Communication

By Jiawei Wang

In this note, we will look at some of the issues related to this

Interprocess Communication(IPC)

There are three

issues here:

1. How one process can pass information to another? 2.

How can we make sure two or more processes do not get into each other’s

way when engaging in critical activities? 3. How to make sure the

sequence of related processes?(i.e. one process must run after

another)

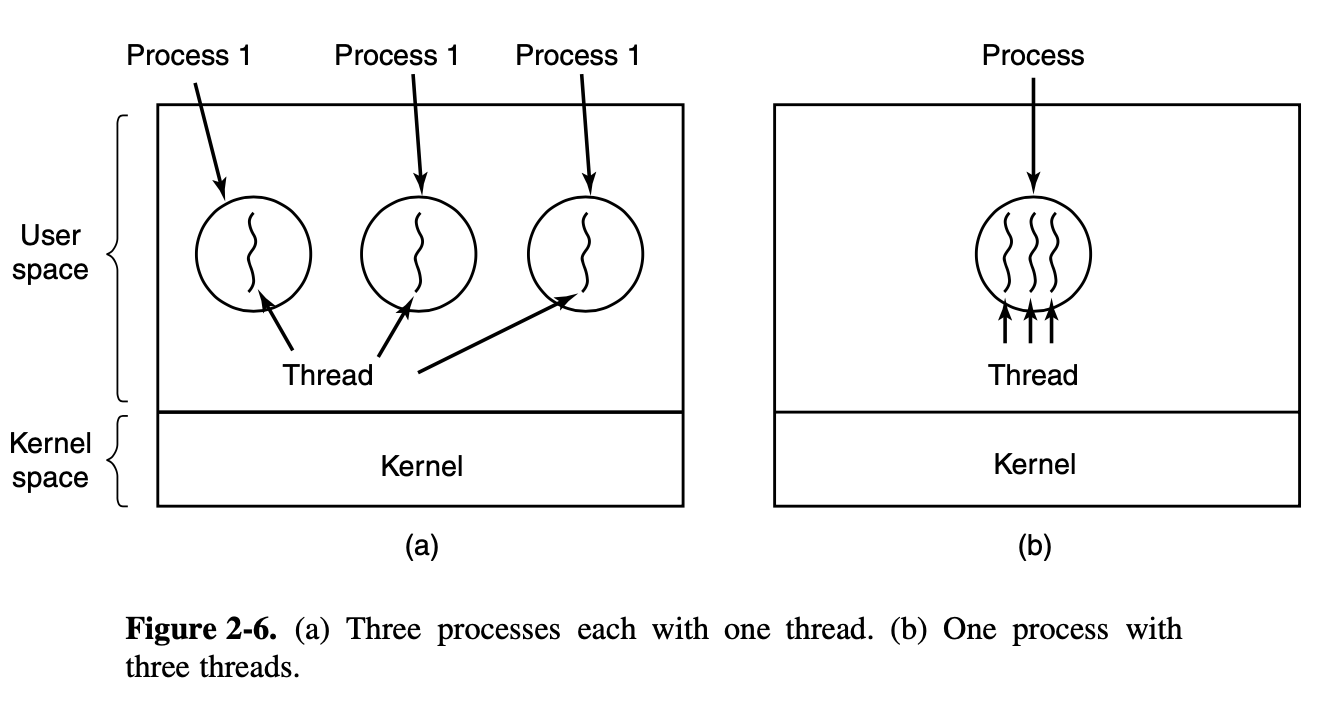

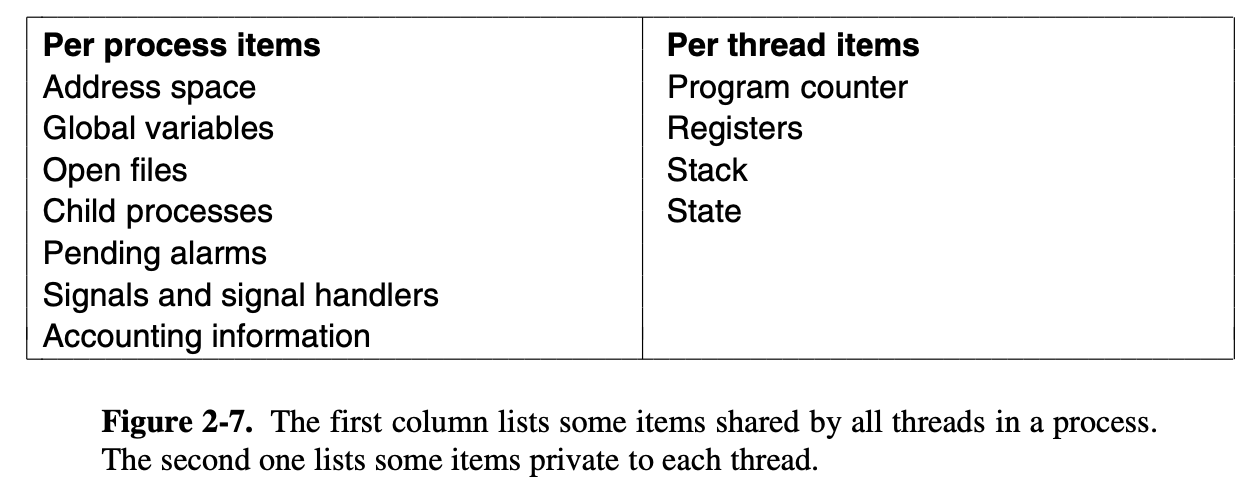

1. Thread

Thread is also called as “lightweight

process”.

Means there are often situations to have multiple

processes of control in the same address space. ###

Introduction Example: Codes/threads.c

int x = 2;

// threads shared memory

void* routine() {

x++;

printf("Test from threads %d\n", getpid());

sleep(3);

printf("The value of x is %d\n", x);

}

void* routine2() {

printf("Test from threads %d\n", getpid());

sleep(3);

printf("The value of x is %d\n", x);

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

pthread_t t1, t2;

// pthread_create 2nd parameter is the property of this thread

// 4th parameter is the arguments of function(3rd parameter)

if (pthread_create(&t1, NULL, &routine, NULL) != 0) return 1;

if (pthread_create(&t2, NULL, &routine2, NULL) != 0) return 2;

// pthread_join is used for waiting the return of the thread (otherwise the thread will not be executed)

// the 2nd parameter is the addr of storing the return value

pthread_join(t1, NULL);

pthread_join(t2, NULL);

return 0;

}We use the POSIX P-threads package to simulating threads in C

language.

Output:

❯ ./a.out

Test from threads 81205

Test from threads 81205

The value of x is 3

The value of x is 3These two threads shares the same address location and belong to the

same process.

Thread vs Process

When several processes each have multiple threads, we have two levels of parallelism present:

1. Process level

- Process Scheduler (Inside kernel)

- Please refer OSDI 5. Process Scheduler

- Scheduling is absolutely required on two occasions:

- When a process exits. (

dequeue()) - When a process block(waiting) on I/O, or a semaphore.

(

enqueue())

- When a process exits. (

- Scheduling is not necessary but usually at these

times:

- When a new process is created.

(

enqueue()) - When an I/O (hardware) interrupt occurs.

(

hwint() -> dequeue() enqueue()) - When a clock interrupt occurs.

(

dequeue() + enqueue())

- When a new process is created.

(

2. Threads level

Thread Scheduler (“Inside” each process)

For the user-level threads:

- The kernel is not aware of the existence of threads, It operates as it always does.

- Picking a process e.g, A, and giving A control for its quantum.

- The thread scheduler inside A decides which thread to run, say A1.

- Since there are no clock interrupts to multiprogram threads, this thread may continue running as long as it wants to. If it uses up the process’ entire quantum, the kernel will select another process to run.

For the kernel-level threads:

- Unlike user-level, the kernel can pick a particular thread to run.

- Like process, the thread is given a quantum and is forceably suspended if it exceeds the quantum.

The major difference between user-level and kernel-level threads is the Performance

- Doing a thread switch with user-level threads takes a handful of machine instructions. since all threads will inside one address space.

- Switching kernel-level threads requires a full context switch. (changing the memory map, invalidating the cache)

Note that in order to facilitate implementation in C

language,

I will use threads instead of processes to introduce some

interprocess examples.

Below we will discuss the problem in

the context of threads.

But please keep in mind that

the same problems and solutions also apply to

processes.

2. Race Condition

Example: Codes/race.c

int mails = 0;

void* routine() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

mails++;

// read mails:

// movl _mails(%rip), %eax

// increment

// addl $1, %eax

// write mails

// movl %eax, _mails(%rip)

}

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

pthread_t p1, p2;

if (pthread_create(&p1, NULL, &routine, NULL) != 0) {

return 1;

}

if (pthread_create(&p2, NULL, &routine, NULL) != 0) {

return 2;

}

// waiting for threads finish

pthread_join(p1, NULL);

pthread_join(p2, NULL);

// race condition

printf("Number of mails: %d\n", mails); // Number of mails: 1289819

return 0;

}

}Before I give the output, let’s see the program - which plus

one to the mails (1000000 x 2) times

❯ ./a.out

Number of mails: 1289819But it give me the 1289819 instead of

2000000 we expected.

Why this

happend?

Processes or threads that are working together may share some common

storage that each one can read and write.

When two or more

processes(threads) are reading or writing some shared data at the same

time.

This may cause Race Condition.

This video

explains the causes of Race Condition.

When we check the assembly code of mail++;

inside the for loop:

movl _mails(%rip), %eax ## read mails

addl $1, %eax ## increment

movl %eax, _mails(%rip) ## write mailsAs I metioned in Introduction

to Processes:

> At any instant of time, the CPU is

running only one program

Imagine that when thread#1 executes at mail++. At that

time he executes the first line of the assembly code.

Which put the

current mail value into a CPU register %eax.

Then

assume the Prcocess Scheduler temporary blocked this

thread#1 let’s say the algorithm may think that it runs too long. And

let thread#2 who is waiting to run.

Let’s assume at that

time, the value of mail is 27. Now stored in

register %eax of thread#1.

Then thread#2 start

to run. At some time (like 0.1 secs after), the Process

Scheduler temporary blocked thread#2 and wake up thread#1

because of the same reason.

thread#2 add mails

multiple times, let’s assume the value of mails is

48.

Now here comes the Race

Condition:

Back to thread#1, When thread#1 restore all the

value of registers and start running

(movl %eax, _mails(%rip)).

Now the

mails becomes 28! instead of 49

we wished!

The difficulty above occurred because

thread#2 started using one of the shared variables before thread#1 was

finished with it.

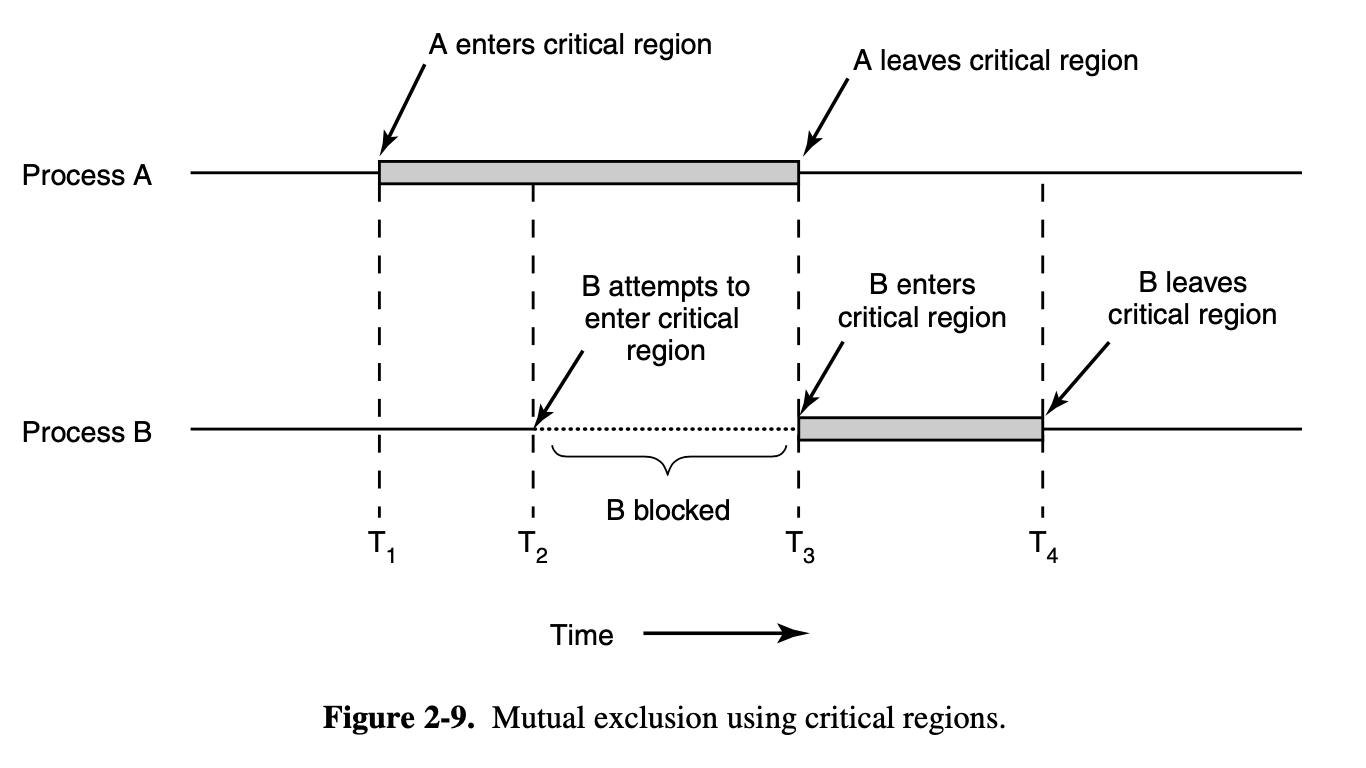

3. Mutual Exclusion

How to avoid Race Conditions?

The key to

preventing trouble here and in many other situations involving shared

memory, shared files, and shared everything else is to find some way to

prohibit more than one process from reading and writing the

shared data at the same time.

Put in other words, what we need is mutual exclusion

— some way of making sure that if one process is using a shared variable

or file, the other processes will be excluded from doing the same

thing.

Here I will give two ways to avoid Race

Conditions: 1. Strict Alternation 2. Mutexes (Binary

Semaphore)

Strict Alternation

Example: Codes/mutual.c

int mails = 0;

int turn = 0;

void* routine1() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

while(turn != 0); // busy waiting

mails++;

turn = 1;

}

}

void* routine2() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

while(turn != 1); // busy waiting

mails++;

turn = 0;

}

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

pthread_t p1, p2;

if (pthread_create(&p1, NULL, &routine1, NULL) != 0) {

return 1;

}

if (pthread_create(&p2, NULL, &routine2, NULL) != 0) {

return 2;

}

// waiting for threads finish

pthread_join(p1, NULL);

pthread_join(p2, NULL);

// race condition

printf("Number of mails: %d\n", mails); // Number of mails: 2000000

return 0;

}By adding an int variable turn to the

program.

We can make sure in any time, only one thread can run in the

critical region.

This code gives us the right example in most cases.

But in some

cases, like thread#2 runs much long in noncritical region than

thread#1:

> Page 92:

When process 0 leaves the

critical region, it sets turn to 1, to allow process 1 to enter its

critical region.

Suppose that process 1 finishes its critical region

quickly, so both processes are in their noncritical regions, with turn

set to 0. Now process 0 executes its whole loop quickly, exiting its

critical region and setting turn to 1. At this point turn is 1 and both

processes are executing in their noncritical regions.

Suddenly, process 0 finishes its noncritical region and goes back to the top of its loop. Unfortunately, it is not permitted to enter its critical region now, because turn is 1 and process 1 is busy with its noncritical region. It hangs in its while loop until process 1 sets turn to 0. Put differently, taking turns is not a good idea when one of the processes is much slower than the other.

Another problem it will caused is called “Busy

Waiting”

Inside the for-loop each iterations, there is a

while-loop continuously testing a variable until some value

appearsm.

This is called busy waiting.

It should

usually be avoided, since it wastes CPU time. Only when there is a

reasonable expectation that the wait will be short is busy waiting

used.

Mutexes

A mutex is a variable that can be in one of two states:

unlocked or locked.

Two procedures are used with

mutexes:

* When a process (or thread) needs access to a

critical region, it calls mutex_lock().

If the mutex is

currently unlocked (meaning that the critical region is available), the

call succeeds and the calling thread is free to enter the critical

region.

* On the other hand, if the mutex is already locked, the

caller is blocked until the process in the critical region is finished

and calls mutex_unlock().

Example Codes/mutex.c

int mails = 0;

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

void* routine() {

for (int i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

mails++; // any time, only one thread can run this instruction

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

}

}

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

pthread_t p1, p2;

pthread_mutex_init(&mutex, NULL); // deafult

if (pthread_create(&p1, NULL, &routine, NULL) != 0) {

return 1;

}

if (pthread_create(&p2, NULL, &routine, NULL) != 0) {

return 2;

}

// waiting for threads finish

pthread_join(p1, NULL);

pthread_join(p2, NULL);

pthread_mutex_destroy(&mutex);

printf("Number of mails: %d\n", mails); // Number of mails: 2000000

return 0;

}4. Condition Variable

Let’s now focus on the 3rd question we metioned in the

begining:

How to make sure the sequence of related processes?

Consider that case - A gas station.

Assumue that a gas station can produce 15 liter petrol per

seconds, and there are many cars waiting for refueling.

Each cars need to be fueled 40 liters once and then

leave.

In this case, we cannot recieve more

cars when the gas station is out of fuel.

There must have a

sequence between two events:

* The gas station has more than 40

liter gas. * Here comes the car to be refueled.

The solution lies in the introduction of condition

variables.

Along with three operations on them,

wait, signal

and boardcast.

waitThis action causes the calling process(thread) to block, and waiting for thesignalfrom other processes(threads) to wake it up.signalWake up one process(thread) waiting on this condition variable (if any).

If a signal is done on a condition variable on which several processes are waiting, only one of them, determined by the process scheduler, is revived.boardcastWake up all waiting processes(threads)

Example: Code/conditionvar.c

// condition variable -- for sequence

pthread_mutex_t mutexFuel;

pthread_cond_t condFuel;

int fuel = 0;

void* fuel_filling(void* arg) {

while (1) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutexFuel);

fuel += 15;

printf("Filled fuel... %d\n", fuel);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutexFuel);

pthread_cond_signal(&condFuel);

sleep(1);

}

}

void* car(void* arg) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutexFuel);

while (1) {

while (fuel < 40) {

printf("No fuel. Waiting...\n");

// every time when got a signal from other threads by calling pthread_cond_signal()

// it will be executed after that wait

pthread_cond_wait(&condFuel, &mutexFuel);

}

fuel -= 40;

printf("Got fuel. Now left: %d\n", fuel);

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutexFuel);

}

}