Operating Systerms Design and Implementation Notes

3. MINIX

By Jiawei Wang

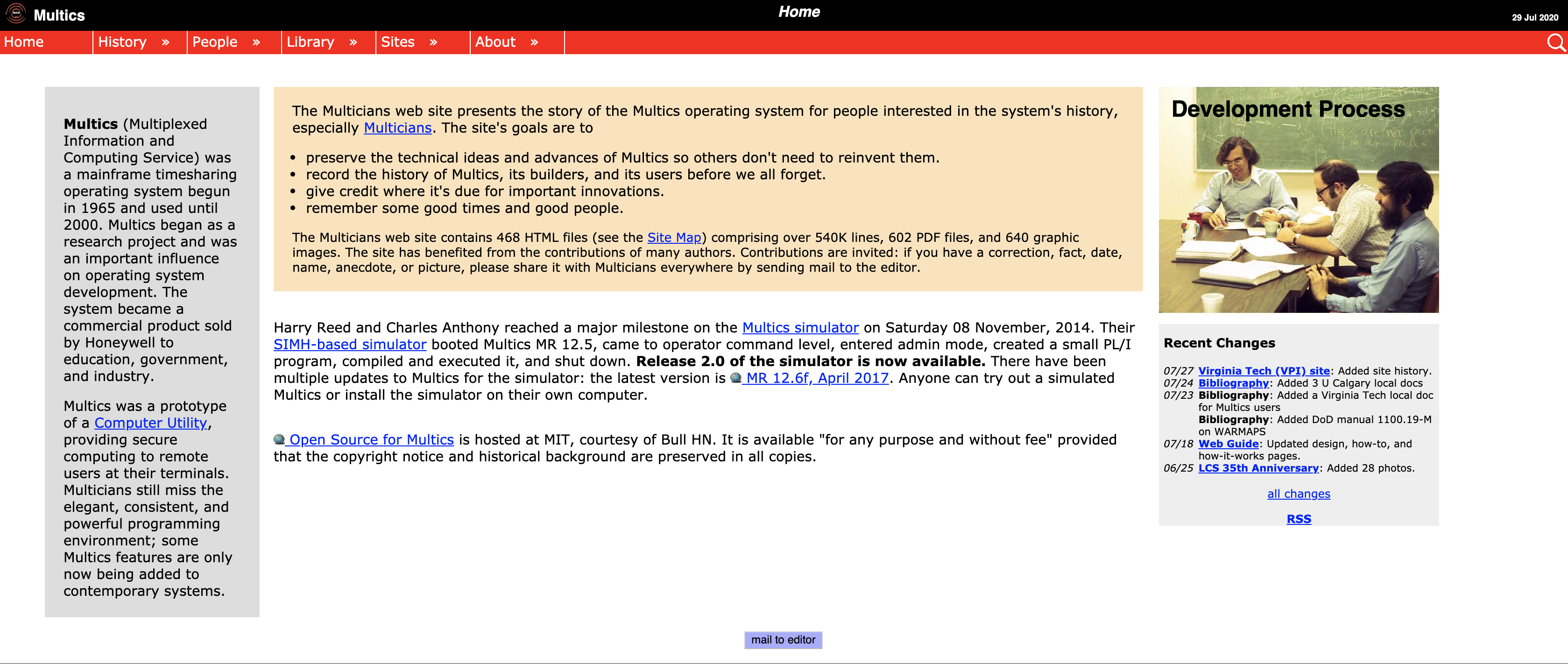

In 1964, IBM announced the launch of a total of six specifications of the System 360 series of computers (the price ranges from the lowest 130,000 dollars to the top version asking for 5.5 million dollars)

The Greatness of System 360 is not that it has any superior

design or performance (although it did excel in this field at the time),

but that it completely reversed people’s overall understanding of

computer systems. Starting with the System 360 series, compatibility

between different hosts and different models has become the fundamental

value of the information industry, and each “computer” has since become

a set of “computer systems” with fixed specifications.

That also means the development of peripherals such as watch

machines, software, and memory finally has profitable value (there are

fixed specifications between computers, so that peripherals can be

universally compatible with them), and IBM has created the entire

industry almost exclusively by hand.

1. The Problem of Systerm/360

The greatest strength of the ‘‘one family’’ idea was

simultaneously its greatest weakness. The intention was that all

software, including the operating system, OS/360, had to work on all

models. It had to run on small systems.

There was no way that IBM

(or anybody else) could write a piece of software to meet all those

conflicting requirements. The result was an enormous and extraordinarily

complex operating system, probably two to three orders of magnitude

larger than FMS. It consisted of millions of lines of assembly language

written by thousands of programmers, and contained thousands upon

thousands of bugs, which necessitated a continuous stream of new

releases in an attempt to correct them. Each new release fixed some bugs

and introduced new ones, so the number of bugs probably remained

constant in time.

Although third-generation

operating systems were well suited for big scientific calculations and

massive commercial data processing runs, they were still basically batch

systems.

Many programmers pined for the

first-generation days when they had the machine all to themselves for a

few hours, so they could debug their programs quickly. With

third-generation systems, the time between submitting a job and getting

back the output was often hours, so a single misplaced comma could cause

a compilation to fail, and the programmer to waste half a day.

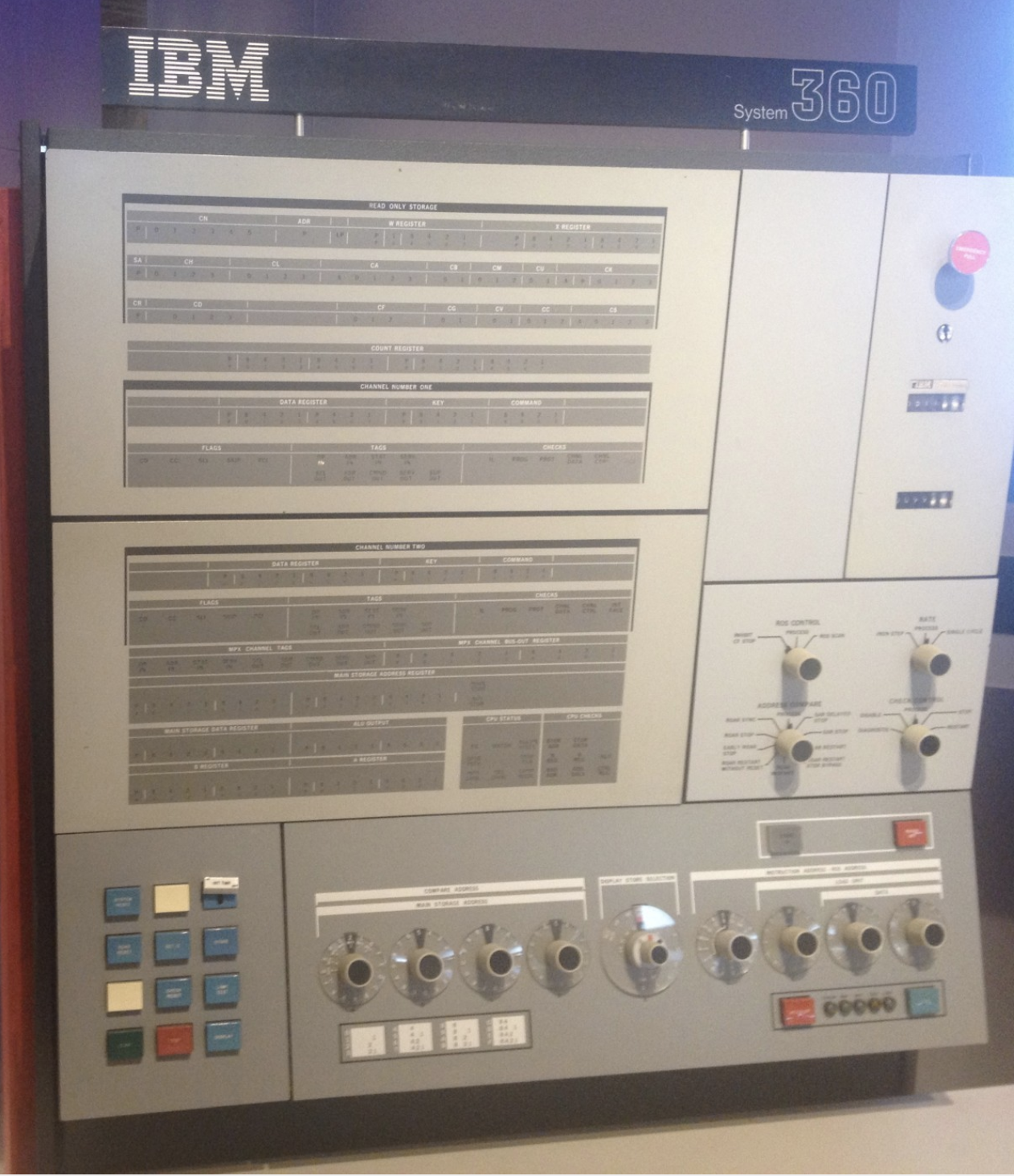

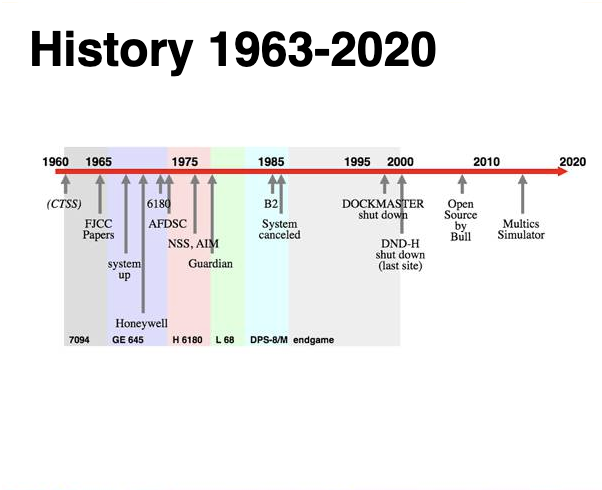

2. CTSS and MULTICS

This desire for quick response time paved the way for

timesharing, a variant of multiprogramming, in which each user has an

online terminal. In a timesharing system, if 20 users are logged in and

17 of them are thinking or talking or drinking coffee, the CPU can be

allocated in turn to the three jobs that want service. Since people

debugging programs usually issue short commands (e.g., compile a five

page procedure) rather than long ones (e.g., sort a million-record

file), the computer can provide fast, interactive service to a number of

users and perhaps also work on big batch jobs in the background when the

CPU is otherwise idle.

The first serious timesharing system,

CTSS (Compatible Time Sharing System), was developed at M.I.T. on a

specially modified 7094 (Corbato ́et al., 1962).

After the success of the CTSS system, MIT, Bell Labs, and

General Electric decided to embark on the development of a ‘‘computer

utility,’’ a machine that would support hundreds of simultaneous

timesharing users.

> Their model was the

electricity distribution system—when you need electric power, you just

stick a plug in the wall, and within reason, as much power as you need

will be there.

The designers of this system, known as MULTICS (MULTiplexed

Information and Computing Service), envisioned one huge machine

providing computing power for everyone in the Boston area.

It was

designed to support hundreds of users on a machine only slightly more

powerful than an Intel 80386-based PC. In addition, MULTICS was

enormously ambitious for its time, much like Charles Babbage’s

analytical engine in the nineteenth century.

3. Unix

MULTICS introduced many seminal ideas into the computer

literature.

But turning it into a serious product and a commercial

success was a lot harder than anyone had expected.

In 1969, Bell Labs dropped out of the project. Then General

Electric quit the computer business altogether.

However, M.I.T. persisted and eventually got MULTICS

working.

It was ultimately sold as a commercial product by the company that bought GE’s computer business (Honeywell) and installed by about 80 major companies and universities worldwide. While their numbers were small.

MULTICS users were fiercely loyal. General Motors, Ford, and the U.S. National Security Agency, for example, only shut down their MULTICS systems in the late 1990s. The last MULTICS running, at the Canadian Department of National Defence, shut down in October 2000.

Despite its lack of commercial success, MULTICS had a huge

influence on subsequent operating systems.

One of the computer scientists at Bell Labs who had worked on

the MULTICS project, Ken Thompson, subsequently found a small PDP-7

minicomputer that no one was using and set out to write a stripped-down,

one-user version of MULTICS. This work later developed into the UNIX

operating system, which became popular in the academic world, with

government agencies, and with many companies.

Another major development during the third generation was the phenomenal growth of minicomputers, starting with the Digital Equipment Company (DEC) PDP-1 in 1961. The PDP-1 had only 4K of 18-bit words, but at $120,000 per ma- chine (less than 5 percent of the price of a 7094), it sold like hotcakes. For certain kinds of nonnumerical work, it was almost as fast as the 7094 and gave birth to a whole new industry. It was quickly followed by a series of other PDPs (unlike IBM’s family, all incompatible) culminating in the PDP-11.

4. Minix

When UNIX was young (Version 6), the source code was widely

available, under AT&T license, and frequently studied. John Lions,

of the University of New South Wales in Australia, even wrote a little

booklet describing its operation, line by line (Lions, 1996). This

booklet was used (with permission of AT&T) as a text in many

university operating system courses. J.lions

Unix

But When AT&T released Version 7, it dimly began to realize that UNIX was a valuable commercial product, so it issued Version 7 with a license that prohibited the source code from being studied in courses, in order to avoid endangering its status as a trade secret. Many universities complied by simply dropping the study of UNIX and teaching only theory.

To remedy this situation, one of the authors of this book

(Tanenbaum) decided to write a new operating system from scratch that

would be compatible with UNIX from the user’s point of view, but

completely different on the inside. By not using even one line of

AT&T code, this system avoided the licensing restrictions, so it

could be used for class or individual study. In this manner, readers

could dissect a real operating system to see what is inside, just as

biology students dissect frogs. It was called MINIX and was released in

1987 with its complete source code for anyone to study or

modify.

Comparing with Unix. Minix has these advantages: * The name MINIX stands for mini-UNIX. Because it is small enough (In Minix3. It only has about 4000 lines C codes) * UNIX was designed to be efficient. But MINIX was designed to be readable.

In the Next Note. We will continue talk about The Development of Computer Oprating Systerm