Operating Systerms Design and Implementation Notes

2. The History of Oprating Systerm(Early)

By Jiawei Wang

- 1. The First Generation (1945–55) Vacuum Tubes and Plugboards

- 2. The Second Generation (1955–65) Transistors and Batch Systems

Operating systems have been evolving through the

years.

The first true digital computer was designed

by the English mathematician Charles Babbage (1792–1871).

Although

Babbage spent most of his life and for trying to build his ‘‘analytical

engine,’’ he never got it working properly because it was purely

mechanical, and the technology of his day could not produce the required

wheels, gears, and cogs to the high precision that he

needed.

Needless to say, the analytical engine did not have an

operating system.

1. The First Generation (1945–55) Vacuum Tubes and Plugboards

After Babbage’s

unsuccessful efforts, little progress was made in constructing digital

computers until World War II. Around the mid-1940s, Howard Aiken at

Harvard University, John von Neumann at the Institute for Advanced Study

in Princeton, J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchley at the University of

Pennsylvania, and Konrad Zuse in Germany, among others, all succeeded in

building calculating engines. The Calculating Engines

used mechanical relays but were very slow, with cycle times measured in

seconds.

Then were replaced by vancuum tubes.

These machines were enormous, filling up entire rooms with tens of

thousands of vacuum tubes, but they were still millions of times slower

than even the cheapest personal computers available today.

In these early days, a single group of people designed, built, programmed, operated, and maintained each machine. All programming was done in absolute machine language, often by wiring up plugboards to control the machine’s basic functions. At that time. Programming languages were unknown (even assembly language was unknown). Operating systems were unheard of!

The usual mode of operation was for the programmer to sign up for a block of time on the signup sheet on the wall, then come down to the machine room, insert his or her plugboard into the computer, and spend the next few hours hoping that none of the 20,000 or so vacuum tubes would burn out during the run. Virtually all the problems were straightforward numerical calculations, such as grinding out tables of sines, cosines, and logarithms.

2. The Second Generation (1955–65) Transistors and Batch Systems

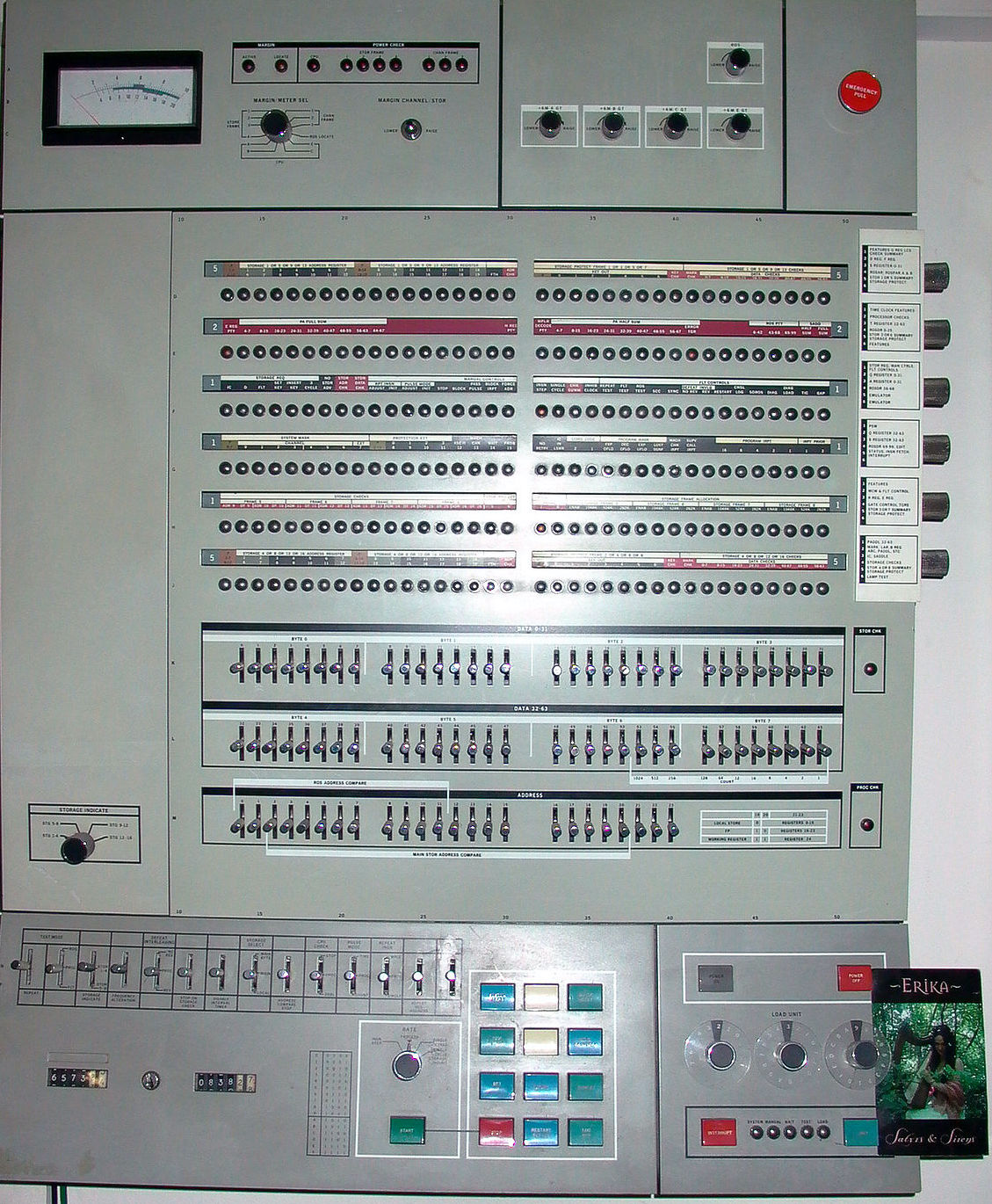

IBM7094

from colunbia.edu

IBM7094

from colunbia.edu

The introduction of the transistor in

the mid-1950s changed the picture radically.

At

that time Computers became reliable enough that they could be

manufactured and sold to paying customers with the expectation that they

would continue to function long enough to get some useful work

done.

And that is the first time, there was a clear

separation between designers, builders, operators, programmers, and

maintenance personnel.

> These machines, now

called mainframes, were locked away in specially air-conditioned

computer rooms, with staffs of specially-trained professional operators

to run them. Only big corporations or major government agencies or

univer- sities could afford their multimillion dollar price tags. To run

a job (i.e., a pro- gram or set of programs), a programmer would first

write the program on paper (in FORTRAN or possibly even in assembly

language), then punch it on cards. He would then bring the card deck

down to the input room and hand it to one of the operators and go drink

coffee until the output was ready.

When the computer finished whatever job it was currently running, an operator would go over to the printer and tear off the output and carry it over to the out- put room, so that the programmer could collect it later. Then he would take one of the card decks that had been brought from the input room and read it in. If the FORTRAN compiler was needed, the operator would have to get it from a file cabinet and read it in.

Much computer time was wasted while operators were walking

around the machine room.

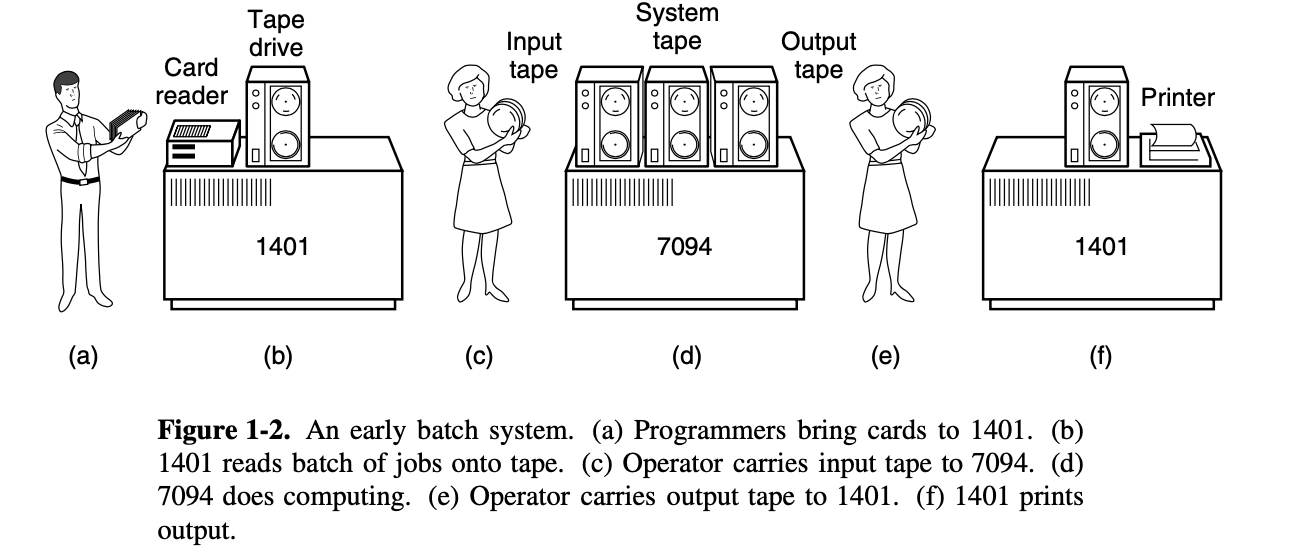

To save time and the

Computing sources(Computer is a high cost equipment). The solution

generally adopted was the batch system

The

idea behind it was to collect a tray full of jobs in the input room and

then read them onto a magnetic tape using a small (relatively)

inexpensive computer, such as the IBM 1401, which was very good at

reading cards, copying tapes, and printing output, but not at all good

at numerical calculations. Other, much more expensive machines, such as

the IBM 7094, were used for the real computing.

Here are the Process:

> After

about an hour of collecting a batch of jobs, the tape was rewound and

brought into the machine room, where it was mounted on a tape drive. The

opera- tor then loaded a special program (the ancestor of today’s

operating system), which read the first job from tape and ran it. The

output was written onto a second tape, instead of being

printed.

After each job finished, the operating system automatically read the next job from the tape and began running it. When the whole batch was done, the operator removed the input and output tapes, replaced the input tape with the next batch, and brought the output tape to a 1401 for printing off line (i.e., not connected to the main computer).

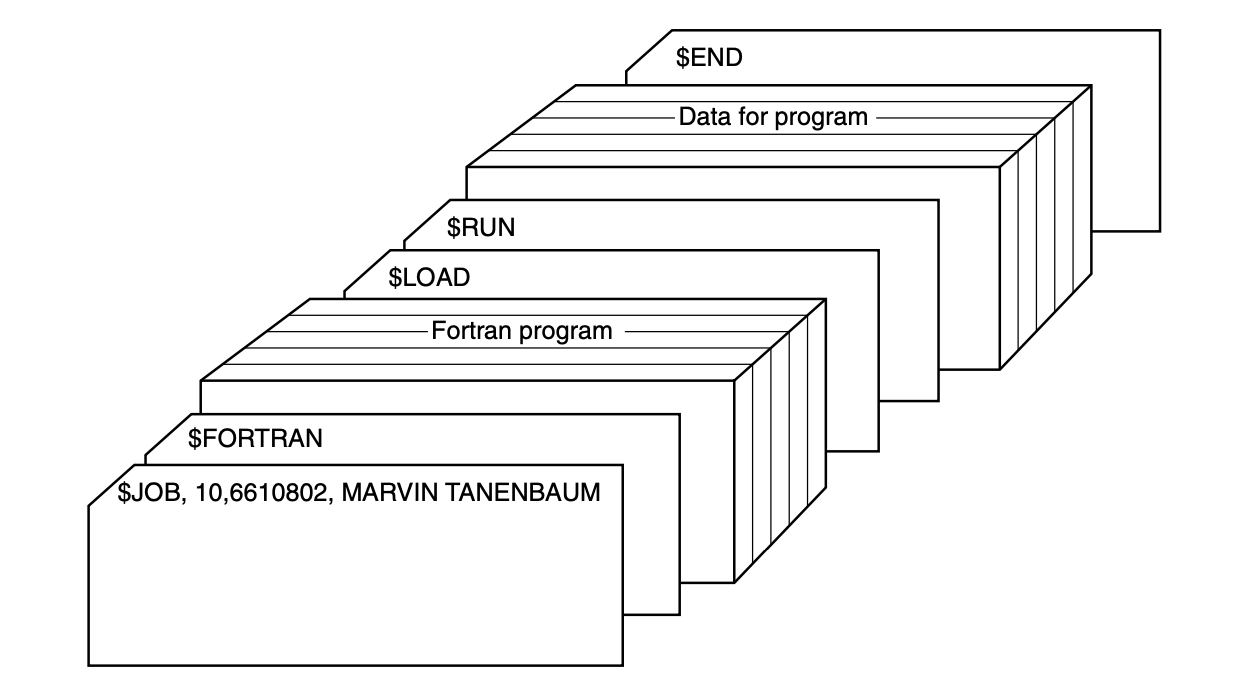

To make a better understand. Let’s see more details of the

input job:

+ It started out with a $JOB card,

specifying the maximum run time in minutes, the account number to be

charged, and the programmer’s name. + Then came a

$FORTRAN card, telling the operating system to load the FORTRAN compiler

from the system tape. It was followed by the program to be

compiled.

+ Then a $LOAD card, directing the

operating system to load the object program just compiled. (Compiled

programs were often written on scratch tapes and had to be loaded

explicitly.)

+ Next came the $RUN card, telling the

operating system to run the program with the data following it.

+ Finally, the $END card marked the end of the job.

These primitive control cards were the forerunners of modern

job control languages and command interpreters.

Large second-generation computers were used mostly for

scientific and engineering calculations, such as solving the partial

differential equations that often occur in physics and engineering. They

were largely programmed in FORTRAN and assembly language. Typical

operating systems were FMS (the Fortran Monitor System) and IBSYS, IBM’s

operating system for the 7094.

3. The Third Generation (1965–1980) ICs and Multiprogramming

By the early 1960s, most computer manufacturers had two

distinct, and totally incompatible, product lines. On the one hand there

were the word-oriented, large-scale scientific computers, such as the

7094, which were used for numerical calculations in science and

engineering. On the other hand, there were the character-oriented,

commercial computers, such as the 1401, which were widely used for tape

sorting and printing by banks and insurance companies.

Developing, maintaining, and marketing two completely

different product lines was an expensive proposition for the computer

manufacturers. In addition, many new computer customers initially needed

a small machine but later outgrew it and wanted a bigger machine that

had the same architectures as their current one so it could run all

their old programs, but faster.

The advent of System/360 means that computers in the world

have a common way of interacting. They all share the operating system

codenamed OS/360, and not all other products have replaced the

customized operating system. Applying a single operating system to the

entire series of products is the key to System/360’s success. And

because of that: Application-level compatibility (with some

restrictions) for System/360 software is maintained to the present day

with the System z mainframe servers.

IBM Systerm 360 Model 65 upload by

Michael J.Ross

IBM Systerm 360 Model 65 upload by

Michael J.Ross

The development process of System/360 is regarded as the biggest gamble in the history of computer development. In order to develop System/360, a large computer, IBM decided to recruit more than 60,000 new employees and establish five new factories.

Gene Amdal is the chief architect of the system, and then the project manager Frederick P. Brooks (Jr.) later wrote “The Mythical Man-Month: The Way of Software Project Management” based on the development experience of this project

The 360 was a series of software-compatible machines ranging from 1401-sized to much more powerful than the 7094. The machines dif- fered only in price and performance (maximum memory, processor speed, number of I/O devices permitted, and so forth). Since all the machines had the same architecture and instruction set, programs written for one machine could run on all the others, at least in theory. Furthermore, the 360 was designed to handle both scientific (i.e., numerical) and commercial computing. Thus a single family of machines could satisfy the needs of all customers. In subsequent years, IBM has come out with compatible successors to the 360 line, using more modern technology, known as the 370, 4300, 3080, 3090, and Z series.

The 360 was the first major computer line to use (small-scale) Integrated Circuits (ICs), thus providing a major price/performance advantage over the second generation machines, which were built up from individual transistors. It was an immediate success, and the idea of a family of compatible computers was soon adopted by all the other major manufacturers.